Plagues and Peoples (25 page)

Read Plagues and Peoples Online

Authors: William H. McNeill

Tags: #Non-fiction, #20th Century, #European History, #disease, #v.5, #plague, #Medieval History, #Social History, #Medical History, #Cultural History, #Biological History

What probably happened between 1331 and 1346 therefore, was that as plague spread from caravanserai to caravanserai across Asia and eastern Europe, and moved thence into adjacent human cities wherever they existed, a parallel movement into underground rodent “cities” of the grasslands also occurred. In human-rat-flea communities above ground,

Pasteurella pestis

remained an unwelcome and lethal visitor, unable to establish permanent lodgment because of the immunity reactions and heavy die-off it provoked among its hosts. In the rodent burrows of the steppe, however, the bacillus found a permanent home, just as it was later to do among the burrowing rodent communities of North America, South Africa, and South America in our own time.

20

Yet epidemiological upheavals on the Eurasian steppe, whatever they may have been, were not the only factors in Europe’s disaster. Before the Black Death could strike as it did, two more conditions had to be fulfilled. First of all, populations of black rats of the kind whose fleas were liable to carry bubonic plague to humans had to spread throughout the European continent. Secondly, a network of shipping had to connect the Mediterranean with northern Europe, so as to be able to carry infected rats and fleas to all the ports of the Continent. Very likely the spread of black rats into northern Europe was itself a result of the intensification of shipping contacts between the Mediterranean and northern ports. These date, on a regular basis, from 1291, when a Genoese admiral opened the Strait of Gibraltar to Christian shipping for the first time by defeating Moroccan forces that had hitherto prevented free passage.

21

Improvements in ship design occurring in the thirteenth century made year-round sailing normal for the first time, and rendered the stormy Adantic safe enough for European navigators to traverse even in winter months. Among other things, ships constantly afloat offered

securer and more far-ranging vehicles for rats. Consequently rat populations could and did spread far beyond the Mediterranean limits that seem to have prevailed in Justinian’s time.

Finally, many parts of northwestern Europe had achieved a kind of saturation with humankind by the fourteenth century. The great frontier boom that began about 900 led to a replication of manors and fields across the face of the land until, at least in the most densely inhabited regions, scant forest remained. Since woodlands were vital for fuel and as a source of building materials, mounting shortages created severe problems for human occupancy. In Tuscany, collision between an expanding peasant population and the agricultural resources of the land seems to have occurred even earlier, so that a full century before the Black Death struck, depopulation had begun.

22

On top of this, the climate worsened in the fourteenth century, so that crop failures and partial failures became commoner, especially in northerly lands, as the length and severity of winters increased.

23

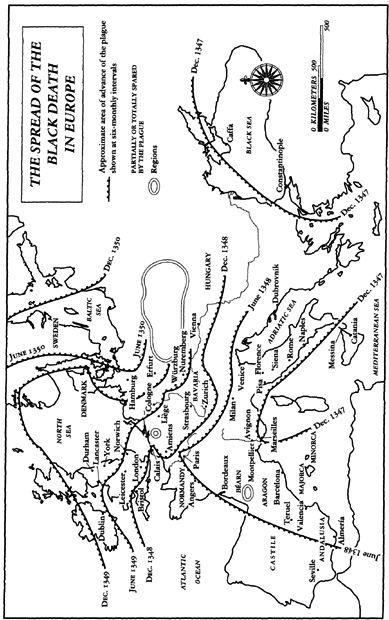

All these circumstances converged at the middle of the fourteenth century to lay the basis for the shattering experience of the Black Death. The disease broke out in 1346 among the armies of a Mongol prince who laid siege to the trading city of Caffa in the Crimea. This compelled his withdrawal, but not before the infection had entered Caffa itself, whence it spread by ship throughout the Mediterranean and ere long to northern and western Europe as well. (See map.)

The initial shock, 1346–50, was severe. Die-offs varied widely. Some small communities experienced total extinction; others, e.g., Milan, seem to have escaped entirely. The lethal effect of the plague may have been enhanced by the fact that it was propagated not solely by flea bites, but also person to person, as a result of inhaling droplets carrying bacilli that had been put into circulation by coughing or sneezing on the part of an infected individual.

24

Infections of the lungs contracted in this fashion were 100 per cent lethal in Manchuria in 1921, and since this is the only time that modern medical men have

been able to observe plague communicated in this manner, it is tempting to assume a similar mortality for pneumonic plague in fourteenth-century Europe.

Whether or not pneumonic plague affected Europeans in the fourteenth century, die-off remained very high. In recent times, mortality rates for sufferers from bubonic infection transmitted by flea bite has varied between 30 and 90 per cent. Before antibiotics reduced the disease to triviality in 1943, it is sobering to realize that in spite of all that modern hospital care could accomplish, the average mortality remained between 60 and 70 per cent of those affected.

25

Despite such virulence, communications patterns of medieval Europe were not so closely knit that everyone was exposed, even though an errant ship and infected rat population could and did bring the plague to remote Greenland and similarly distant outliers of the European heartlands.

26

Overall, the best estimate of plague-provoked mortality, 1346–50, in Europe as a whole is that about one third of the total population died. This is based on a projection upon the whole Continent of probable mortality rates in the British Isles, where the industry of two generations of scholars has narrowed the range of uncertainty to a decrease in population during the plague’s initial onset of something between 20 and 45 per cent.

27

Transferring British statistics to the Continent as a whole at best defines an approximate magnitude for guess-estimation. In northern Italy and French Mediterranean coastlands, population losses were probably higher; in Bohemia and Poland much less; and for Russia and the Balkans no estimates have even been attempted.

28

,

29

Whatever the reality may have been—and it clearly varied sharply from community to community and in ways no one could in the least comprehend—we can be sure that the shock to accustomed ways and expectations was severe. Moreover, the plague did not disappear from Europe after its first massive attack. Instead, recurrent plagues followed at irregular intervals, and with varying patterns of incidence, sometimes rising to a new severity, and then again receding. Places that

had escaped the first onset commonly experienced severe die-off in later epidemics. When the disease returned to places where it had raged before, those who had recovered from a previous attack were, of course, immune, so that death tolls tended to concentrate among those born since the previous plague year.

In most parts of Europe, even the loss of as much as a quarter of the population did not, at first, make very lasting differences. Rather heavy population pressure on available resources before 1346 meant that eager candidates were at hand for most of the vacated places. Only positions requiring relatively high skills—farm managers or teachers of Latin, for instance—were likely to be in short supply. But the recurrences of plague in the 1360s and 1370s altered this situation. Manpower shortages came to be widely felt in agriculture and other humble occupations; the socio-economic pyramid was altered, in different ways in different parts of Europe, and darker climates of opinion and feeling became as chronic and inescapable as the plague itself. Europe, in short, entered upon a new era of its history, embracing as much diversity as ever, since reactions and readjustments followed differing paths in different regions of the Continent, but everywhere nonetheless different from the patterns that had prevailed before 1346.

30

In England, where scholarly study of the plague has achieved by far its greatest elaboration, population declined irregularly but persistently for more than a century, and reached a low point some time between 1440 and 1480.

31

Nothing comparably definite can be said about other parts of Europe, though there is no doubt whatever that plague losses continued to be a significant element in the Continent’s demography until the eighteenth century.

32

If one assumes that population decay lasted about as long on the Continent as in England—an assumption liable to innumerable local exceptions but plausible overall—the period required for medieval European populations to absorb the shock of renewed exposure to plague seems to have been between 100 and 133

years, i.e., about five to six human generations.

33

This closely parallels the time Amerindian and Pacific island populations later needed to make an even more drastic adjustment to altered epidemiological conditions and suggests that, as in the case of Australian rabbits exposed to myxomatosis, 1950–3, there are natural rhythms at work that limit and define the demographic consequences of sudden exposure to initially very lethal infections.

34

Parallel to this biological process, however, was a cultural one, whereby men (and perhaps rats, too) learned how to minimize risks of infection. The idea of quarantine had been present even in 1346. This stemmed from biblical passages prescribing the ostracism of lepers; and by treating plague sufferers as though they were temporary lepers—forty days quarantine eventually became standard—those who remained in good health found a public and approved way to express their fear and loathing of the disease.

35

Since everyone remained ignorant of the roles of fleas and rats in the propagation of the disease until the very end of the nineteenth century, quarantine measures were not always effectual.

Nevertheless, since doing something was psychologically preferable to apathetic despair, quarantine regulations became institutionalized, first at Ragusa (1465), then at Venice (1485); and the example of these two Adriatic trading ports was widely imitated elsewhere in the Mediterranean thereafter.

36

The requirement that any ship arriving from a port suspected of plague had to anchor in a secluded place and remain for forty days without communication with the land was not always enforced, and even when enforced, rats and fleas could sometimes come ashore while human beings were prevented from doing so. All the same, in many cases such precautions must have checked the spread of plague, since, if isolation could be achieved, forty days was quite enough to allow a chain of infection to burn itself out within any ship’s company. The quarantine rules which became general in Christian ports of the Mediterranean in the sixteenth century were therefore well founded.

Yet plague continued to filter past such barriers, and continued to constitute a significant demographic factor in late medieval and early modern times in all parts of Europe. In the Mediterranean, access to the enduring reservoir of rodent infection was especially easy via Black Sea and Asia Minor ports.

37

Outbreaks of plague were therefore frequent enough to keep the quarantine administration of all major ports continuously alive until, in the nineteenth century, new ideas about contagion led to relaxation of old rules.

38

The last important plague outbreak in the western Mediterranean occurred in and around Marseilles, 1720–21; but until the seventeenth century occasional plague outbreaks, carrying off anything up to a third or a half of a city’s population in a single year, were normal.

39

,

40

Venetian statistics, for instance, which became fully reliable by the second half of the sixteenth century, show that in 1575–77 and again in 1630–31, a third or more of the city’s population died of plague.

41

Outside the Mediterranean, European exposure to plague was less frequent and public administration in late medieval and early modern times was less expert. The result was to make visitations of plague rarer and, at least sometimes, also more catastrophic. A particularly interesting case was the outbreak of plague in northern Spain, 1596–1602. One calculation holds that half a million died in this epidemic alone. Subsequent outbreaks in 1648–52 and 1677–85 more than doubled the number of Spaniards who died of plague in the seventeenth century.

Pasteurella pestis

must thus be considered as one of the significant factors in Spain’s decline as an economic and political power.

42

In northern Europe the absence of well-defined public quarantine regulations and administrative routines—religious as well as medical—with which to deal with plague and rumors of plague, gave scope for violent expression of popular hates and fears provoked by the disease. In particular, longstanding grievances of poor against rich often boiled to the surface.

43

Local riots and plundering of private houses sometimes put the social fabric to a severe test.

After the Great Plague of London, 1665,

Pasteurella pestis

withdrew from northwestern Europe, though it remained active in the eastern Mediterranean and in Russia throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Quarantine and other public health measures probably had less decisive overall effect in limiting the outbreaks of plague, whether before or after 1665, than other unintended changes in the manner in which European populations co-existed with fleas and rodents. For instance, in much of western Europe, wood shortages led to stone and brick house construction, and this tended to increase the distance between rodent and human occupants of the dwelling, making it far more difficult for a flea to transfer from a dying rat to a susceptible human.

44

Thatch roofs, in particular, offered ready refuge for rats; and it was easy for a flea to fall from such a roof onto someone beneath. When thatch roofs were replaced by tiles, as happened generally in London after the Great Fire of 1666, opportunities for this kind of transfer of infection drastically diminished. Hence the popular notion that the Great Fire somehow drove the plague from the city probably had a basis in fact.