Pirate Freedom (41 page)

Authors: Gene Wolfe

When I had pulled myself together, I said, "Who taught you English?"

"Master."

I got a little bit more than that out of him that day, but not much. Later, Novia and I got a little bit more. If I were to space it all out the way we got it, it would drive you crazy. So I am just going to give the gist of it here and let it go at that.

Hoodahs was a Moskito who had signed up with Captain Swan. They had raided down the Atlantic coast of South America, and maybe around the Horn. (Hoodahs's geography was pretty sketchy.) Eventually they had put in at some islands where there were rocks, trees, and goats, and not much else, hoping to shoot fresh meat. Hoodahs had been in the hunting party, and he had been left behind. Our guess was that a Spanish ship had come up, but it could have been no more than a change in the weather.

Eventually, he made a little raft and paddled it to one of the other islands. There had been a white man on it, and they had made friends and joined forces. Hoodahs called this man Master. Master had taught him English, and more or less converted him to Christianity. By that I mean he still believed everything Moskitos do, but he knew about God and Jesus, too, and I think may have liked them better.

They started building a real boat together, cutting little trees, sawing planks, seasoning the wood, and so forth. They had gotten pretty far with it, from what he said, when a ship came. Master went aboard to go back to England, but Hoodahs did not. Part of it was that he did not want to go to England, and part was that he did not trust the men on the ship. Or that is how it seemed to Novia and me.

He stayed on the island and stopped working on their boat. As well as I can figure, he was on the first island for a year or so, then with Master for at least two years and maybe longer. After that he was alone on Master's island for at least another year.

Spanish ships had come from time to time, and he and Master had al

ways hidden their boat and hidden themselves, too. This time Hoodahs hid, but forgot to hide the boat—or maybe could not carry it by himself. These Spanish had dogs, and the dogs hunted him down. The Spanish caught him and made him a slave on their ship. Eventually they had sold him to the innkeeper.

As I said, I got a whole lot less than that when we were out on the boat. I am not sure whether Mahu was the most talkative man I have ever met, but I am absolutely certain that Hoodahs was the most closemouthed. I told him not to speak English to Spaniards, and warned him that he was never to tell anybody I did. At first I worried that he might do it anyway. As I got to know him better, I realized that I had wasted my breath telling him to clam up. Hoodahs was not big on telling anybody anything, and that is putting it mildly.

Nobody had stopped us, or questioned us, or made any other kind of trouble, so the next day we went fishing again, this time south into Lake Maracaibo. It was a funny setup. The eastern shore of the lake was Spanish, with a lot of agriculture and a little town called Gibraltar down toward the south end. The western shore was still wild jungle, with Native Americans there that the Spanish called Indios Bravos. Boats that came too close to their side were likely to be in trouble. I asked Hoodahs whether he wanted to join the Indios Bravos, saying that he could dive over the side and swim, and it would be okay with me. I would not try to stop him. He said no, the Indios Bravos would kill him, he was not of their tribe.

We stopped at Gibraltar, got some wine and something to eat, and I talked about fishing with a couple of men where we ate. The man who sold us our food said that Hoodahs would have to take his outside, then said that Hoodahs would run away when he saw he was not chained. I said he would not, don't worry about it. He got his food, ate outside, and did not run away.

The day after that, we decided to try the Gulf again. It was a nice setup for defense, with a narrow strait that was too shallow for ships anywhere except right down the middle between Lookout Island and Pigeon Island. The watchtower was on Lookout Island, on top of a little hill that was just about the whole island.

Pigeon Island was bigger, maybe twenty or thirty acres. The fort was stone, built so that any ship that went down the strait to Maracaibo had to sail right under the guns. When I had gotten a look at it two days before, I had seen right away that the only way to capture it was to attack it on the

landward side. Eight or ten big galleons might have been able to knock it down, but they would have lost four or five ships first.

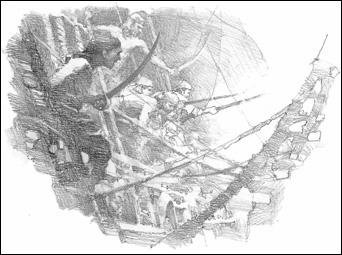

There was a little cove over on the shallow-water side, pretty well hidden by trees. We tied up there, and I explained to Hoodahs that I needed to have a look at that side of the fort without being seen. He said, "Me first. Watch hands," and faded into the underbrush like smoke. I followed him, trying to move fast without making any noise. Trying, I said. I moved less than half as fast as he did, and made ten times more noise. Or a hundred, because he did not make any noise at all, and I did. I would move ahead as fast as I could for five or ten minutes, then I would catch sight of him waiting for me. He would wait to make sure I had seen him, motion for me to follow, and fade out.

After that had happened twice he did not go, but stayed right where he was, pointing. There was a little clearing in front of us, and he was pointing to the other side. I caught up with him and looked across that clearing as hard as I could. What I saw was more trees and more brush. Nothing else.

Hoodahs motioned for me to follow, and faded off to his left, not going into the clearing at all. I am dumb, but I was not dumb enough to step out there. I followed him, and when we had gone maybe twenty or thirty feet, there was a trench about three feet deep with gravel on the bottom, and a thick wall of dirt not quite two feet high in front of it. There were little bushes scattered along the top of that wall, looking like they had been planted there. In front of it were more little bushes, not high enough to block the view of anybody looking over it.

We followed it around until we were looking across the clearing from the other side. Hoodahs came as close to smiling as I ever saw—by which I mean that his mouth was set in stone, but his dark and narrow eyes were laughing—raised an imaginary musket, and pulled back the invisible hammer. I nodded to show I got it, and we went on to the fort and had a good look at that.

A couple of days after that, I got all dressed up in the fancy clothes I had been buying in Maracaibo, strapped on my long sword and Novia's dagger, and Hoodahs and I sailed up to that fort and tied up at the wharf, all as open and aboveboard as you please. I told the colonel I was a soldier, a captain, who had come to Maracaibo from Havana hoping to get a promotion from General Sanchez.

And I showed him the letter that Novia and I had cooked up, complete

with a pretty scarlet ribbon and the smudged red wax impression left by the "official" seal Long Pierre had carved for us. It talked about the good family in Spain I came from (which really was Novia's) and praised me to the skies. I had held the pen that signed it, but the name on it belonged to the governor of Cuba.

When the colonel had read all that, I told him I had been promised an audience with the deputy governor and General Sanchez in a few days, and I wanted to show them I was already familiar with the military situation here.

He stood me a glass of good wine and showed me all over the fort. Which was, I admit, pretty impressive. Impressive from the seaward side, particularly.

I did various other things in Maracaibo after that, sometimes with Hoodahs and sometimes on my own. None of them were important, although some of them were fun.

Then my fortnight was up, and we sailed out to meet Harker in the Gulf and went aboard, tying our little boat on behind

Princess

.

Our Attack

CAPT. BURT WELCOMED

me with a big smile and a glass of wine. "You're lookin' healthy, Chris. How's everythin' on the

Sabina

?"

I said thank you and "Fine, sir. Novia had to shoot one guy while I was gone and hang another one, but she says it's done wonders to bring the rest into line. So do Red Jack and Bouton."

"I've known it to help, myself." Capt. Burt grinned. "You'll be short two men, just the same."

I shook my head. "You're right, sir, she was down two men. The man she hanged had killed Compagne, so that was two. But the one she shot—it was one of the Cimaroons—is recovering. I brought us another man when I came back, so we've only lost one, really."

"You're sure he ain't a spy, Chris?"

"He was a Moskito slave, sir. They just about beat him to death. He hates the Spanish worse than I hate … well, anybody."

"You trust him."

"Absolutely. If you knew him like I do, you'd trust him, too."

"Good enough." Captain Burt leaned back, making the steeple with his fingers. "Tell me about the fort."

"Strong on the water sides, not so strong on the others. The walls fronting the strait are granite, about four feet thick. Landward—"

"How many guns?"

"On the water side? Sixteen. There are ten eight-pounders, four twelve-pounders, and two twenty-fours. They have two furnaces for heating hot shot."

He rubbed his hands together. "You got into the fort, Chris?"

"Yes, sir. It was no great trick."

"I'm impressed. I thought you were a man worth havin' when we met in Veracruz. Remember that?"

"Yes, sir. I'll never forget it."

"I didn't know how right I was. Like some more wine?"

I shook my head and put my hand over my glass.

He poured more for himself. "Now let me count up. Four men for each of the eights, that's thirty-two. Four twelves, you said. Let's say six men for each of them, which is another twenty-four—fifty-six so far. Two twenty-four-pounders. They could be worked by eight, but let's allow ten—another twenty men. There will be officers, men to tend the furnaces, and so on. I'd say a hundred at least. Does that square with what you saw?"

I shook my head again. "It's more like two hundred, Captain. I'd guess about a hundred and sixty. Maybe a hundred and eighty, but at least a hundred and sixty."

He nodded, I would say to himself. "Stand against a fleet. L'Olonnais took the place, you know. Got a fortune out of it and scared Spain half to death. They've made it a lot stronger than it was in his day. Tell me about the watchtower. Is it part of the fort?"

"No, sir, it's not. It's on a different island on the other side of the strait— Isla de la Vigia. It means Lookout Island. It's a stone tower on a hill. I'd guess the tower must be about fifty feet high, but the top of the tower must be close to a hundred feet above sea level. Whenever a ship comes into the Gulf, the tower signals to the fort. I tried to crack the code, but I couldn't."

"I take it the strait's narrow? That's how it looks on every map I've seen."

"Yes, sir. Really narrow, and the channel down it is worse. Narrow and

crooked. There's a famous sandbar called El Tablazo about ten feet down. A lot of ships get hung up on it."

"I've got the picture." The steeple came back. "What would prevent our taking the tower, Chris?"

"Fire from the fort. Soldiers from the fort or from the barracks outside the city."

"There are more soldiers there to defend the city, then."

"Yes, sir. About eight hundred, from what I saw of them."

"Good soldiers?"

I shrugged. "About average, I'd say. I don't know a lot about soldiers."

"Good soldiers stand straight and keep themselves as clean as possible. Like marines." Capt. Burt rose as he spoke, walked to the big stern windows and looked out at

Snow Lady

. "I don't imagine you know much about marines, either."

I said, "No, Captain. I don't."

"I wish I had some. I wish the Navy would lend me a couple of hundred. Or more." As he walked back to his chair, I noticed that the deck beams just cleared his head. I had to crouch in that cabin, just like I crouched in our cabin on

Sabina

.

"I've got two plans to propose, Chris. Maybe they're both workable. Maybe neither one is. I'd like your frank opinion of both."

"Sure," I said. "You'll get it, Captain."

"Good. Here's the first. We land on the western shore of the Gulf, march along the coast staying out of range of the guns of the fort, and take the city."

"Sure." I nodded. "That's what I was thinking when I got there. It might be done, sir, but it carries some big disadvantages."