Pirate Freedom (3 page)

Authors: Gene Wolfe

So I waited for the next customer, figuring I would grab the chicken out of her basket while she was paying. Only the next customer had a basket with a lid, and I saw that my idea was not going to work. She would put it in there and close the lid, and start screaming while I was getting her basket open. What I would have to do instead was grab the chicken as soon as it was put down on the rag.

I tried to, but all I got was a whack from the chicken woman's stick, a stick I had not even noticed she had. It hurt like the devil and I was afraid I was going to get caught, so I ran.

It made me mad, too. Mad at her for whacking me, and mad at myself for not grabbing the chicken. I knew it was going to be a lot tougher when I tried it again, so I waited until the sun was nearly down and some of the stands were closing. That made it easier for me to see from a distance when she had a customer, because there were not as many people. For a while I was afraid she would not have any more.

Finally somebody came, a man. I think he meant to eat his chicken as soon as he got it, because he did not have a basket or anything to carry it in. She got a chicken for him from the wooden cage and showed it to him. He nodded, and she twisted its neck, and plucked and gutted it faster than you would have thought possible.

While it was cooking, I worked in a little closer. And as soon as she had it off her spit, I had it out of her hand. She got me again with her stick and it hurt pretty bad, but I grabbed her stick with my free hand before she could get it back up and got it away from her.

She thought I was going to hit her with it then, but I did not. I just dropped it and ran off with her chicken.

Maybe it tasted as good as the bread. I do not know. All that I remember is how scared I was that I was going to get caught before I finished it. How scared she was too—that short fat woman cowering with her arms up, afraid I was going to brain her with her own stick. When I thought of her just now, that is how I remembered her.

When I had eaten everything and sucked the bones—it did not seem like much—I found another sleeping place, not so near the market and the docks. And when I was lying there thinking about the chicken and getting hit twice with her stick, it came to me that if the lanky man buying the chicken had grabbed me from behind, it would have been all over. I would be in jail, was what I thought. Now I think they would probably have tied me to a post and beaten the merda out of me, then kicked me out. That is how they usually punished people when I was then.

After that, I started thinking about the monastery. Really thinking about it, maybe for the first time ever. How peaceful it had been, and how just about everybody there tried to look out for everybody else. I missed my cell, the chapel, and the refectory. I missed some of my teachers, too, and Brother Ignacio. It was funny, but the thing I missed most of all was the work he and I had done outside—helping milk sometimes, herding the pigs, and weeding. Collecting eggs in a basket like the ones I had hoped to steal out of, and carrying them in to Brother Cook. (His name was José, but everybody called him Brother Cook anyway.)

Then I got to thinking again about the rules, and what they had meant. You could not go into anybody else's cell, not ever, and the cells had no doors on them. You got told when to take a bath, three novices at a time, and there would be a monk there watching the whole time, generally Brother Fulgencio. He was older even than the abbot.

Those were rules I had not thought about at all when I was little. I took them in stride, like I had taken the rules at our school in the States. But when I got older and we learned about being gay and all that, I understood. They had thought we were, and they had not cared as long as we did not actually do anything with another kid. Once I had realized what was going on, it bugged me a lot. I did not want to spend the rest of my life thinking about girls and knowing that the people around me were thinking about boys, and thinking I was, too.

It was that last part that really got to me. If it had not been for that, if there had been a way I could have proved once and for all that I was no leccacazzi, I think I might have stayed.

That got me to thinking about how it was outside. It seemed to me Our Lady of Bethlehem had been a good thing, a good idea Saint Dominic had a thousand years ago: a place where people who did not ever want to fall in

love or get married—or felt like they could not—could go and live really good lives.

But it seemed to me, too, that the world outside the monastery ought to be about the same, only with falling in love and maybe having kids, a place where people liked each other and helped each other, and everybody got to do what he was good at.

That has never changed for me. When you read the rest of this you're not going to believe me, but I am writing the truth. We have to make it like that, and the only way we can do it is for each person to choose it and change. I chose it that night, and if I have slipped up pretty often God knows I am truly sorry about every slip.

Sometimes I have had to slip. I ought to say that, too.

The Santa Charita

I AM NOT

going to tell you much about the next few days. They are not important and run together anyway. I asked various people about another Havana, and they all said there was not one. I asked about my father and his casino, but nobody had heard of it. I walked down every last street in town, and I talked to priests at two churches. They both told me to go back to Our Lady of Bethlehem. I did not want to do that, and I did not think I could even if I tried. Now I hope things are different, but then I was sure I could not. I tried to find work, and sometimes I did get a few hours' work for a little money. Mostly it was around the docks.

Then Señor heard me asking about work. He said, "Pay attention, muchacho. You got a place to sleep?"

I said no.

"Bueno. You need someplace to sleep and meals. You come with me. You

got to work and work hard, but we'll feed you and give you a hammock and a place to sling it, and when we get home you'll get some money."

That is how I got to be on the

Santa Charita

. English sailors talk about signing articles and all that, but I did not really sign anything. The mate I had talked to just talked to the captain, and the captain wrote my name in his book. Then the mate told me to make my mark beside it, so I initialed it and that was all there was to it. I think the mate's name was Gómez, but I have known a lot of people with that name and I may be wrong. We said Señor. He was a little man with big shoulders, and smallpox had given him a really tough time when he was younger. It took me two or three days to get used to the way he looked.

I got a hammock in the forecastle, like he promised. The food was not good except when it was, if you know what I mean. I had never drunk wine before, except just a sip of the Precious Blood at mass sometimes, so I did not know how bad the wine was. Or how weak it was, either. We had been loading cargo for Veracruz, a lot of it live pigs and chickens in cages, and the deck was a mess to the big. We would clean up one side, then the other, then back to the first one. We pumped water out of the harbor and squirted it out of a hose, mostly, and when we were not doing that, we pumped the ship. It leaked. Maybe there are wooden ships somewhere that do not leak, but I have never been on one.

You could go ashore when you were off watch. I did that just like the others, but I could not have gotten drunk or hired a whore even if I had wanted to. (Which I did not.) The Spanish sailors were not nearly as bad about getting drunk as some I have known since, but they were worse about women. The night we sailed they smuggled a battery girl on board and hid her. When we had gotten the anchor up and the pilot was taking us out of the harbor, the captain and Señor pulled her out of the hold and threw her over the side. I had seen something of her by then and had not liked it, but I would never have done that. It was the first thing that made me really understand what kind of a place I had landed in.

The second thing came three or four nights later. When we got off watch and went below, two guys grabbed my arms and another one pulled my jeans down. I fought—or thought I did—and yelled my head off until somebody about knocked it off. You know what happened after that. So did I, after I woke up. The only good thing that came out of it was that my old jeans got ripped so bad that I had to have new pants, and I found out you could get

them from the bosun. He took care of the slop chest. He charged too much against my pay and my new canvas pants were too big, but I was so glad to get rid of those tight jeans I did not care.

About then I started going aloft, making sail and taking it in. Vasco and Simón told me I would be scared to death and dirty my new pants, but I told them they had better be scared, because I was going to grab them if I fell and take them down with me. I meant what I said, too.

The weather was calm with just a little bit of a breeze, you stood on the foot rope and held on with one hand, and I was not scared at all. Besides, you got a great view from up there. I did my work, but I sneaked looks every chance I got. There was the beautiful blue sea, and above us the beautiful blue sky with a couple of little white clouds, and I kept thinking that the earth was a beautiful woman, and the sky was her eyes—and thinking too how the sea and the sky would be there when everybody on our ship was dead and forgotten. I liked that, and I still do.

When we were down on the main deck again, I kept hoping the captain would want to take a reef in the topsail, but he did not. Only by then I knew that we furled all sail at night and lay to. (And I thought all ships did.) So I would get my chance for sure before we went off watch.

Here I ought to say that we were the starboard watch, which meant the one that Señor bossed and the one that did just about all the work. There was a larboard watch, too, which was a lot smaller. The larboard watch could sleep on deck if there was nothing for them to do, and sometimes they shot craps. Our ship was a brig, a bergantin was what we called it. It means that it had two masts the same size, both square-rigged. I was a foremast man then, not that it matters.

While I am filling you in, let me say too that in those days I knew a lot more Spanish sea talk than English, although all the other sailors knew a whole lot more than I did. They would not tell me what they meant, either, just saying that it was a comb to smooth the water or a dildo for a whale or whatever. I had to figure out everything for myself, and I got laughed at if I was even a little bit wrong.

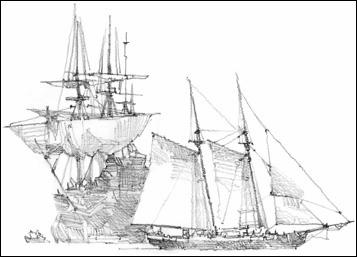

Another thing I did not know then was that our handy bergantin was one of the kinds of ships pirates like best. The others are Bermuda sloops and Jamaica sloops. They are both bigger than most sloops, and a lot faster. The hulls are pretty much the same, and the difference is in the rigs. Everybody has his own tastes, but I always liked the Bermuda rig, myself.

When the sun was on the horizon, we went aloft again and furled the sails, the mainsail first, then the topsail. The stars were coming out and the wind picking up a little, and I remember thinking that sailors were the luckiest people in the world.

As soon we slid down to the deck, we were dismissed and went below and they jumped me again. This time they did not catch me completely off guard, and I fought. Or anyway, I would have called it fighting if anybody had asked. They beat and kicked me until I passed out and they got what they wanted. I did not know then that it was the last time.

I would not call what I did that night fighting, or what I did afterward sleeping, either. Sometimes I was conscious and sometimes I was not. I prayed that God would send me back to Our Lady of Bethlehem. I threw up a couple of times, and one time was on the deck. The larboard watch made me clean that up, although I was so bad I fell down two or three times while I was trying to do it.

The next day el capitán saw how bad I was—both my eyes were swollen just about shut, and I had to hold on to something to keep from falling over—and put me on the larboard watch myself. He did not try to find out who had beaten me or even ask me to tell him. (I think I might have.) He just said I was larboard watch until he changed it, and sent me below. It meant my old watch had to do the same work minus one man, so that was their punishment. When we came on watch about sundown, I made up my mind that they would get some more punishment from me as soon as I felt better.

(All this comes back to me with a vengeance tonight, because of what happened yesterday evening. I made four of our boys in the Youth Center quiet down, and they waited for me to come out at ten. They were all good-sized and pretty strong. Tough, too, they thought. They got in each other's way, and if there was only one of me, every kick and punch did real damage. They finally knocked me down and knocked my wind out. When they had kicked me a couple of times they beat it, practically carrying Miguel. I caught up with them after about three or four blocks.)