Philip Jose Farmer (10 page)

Read Philip Jose Farmer Online

Authors: The Other Log of Phileas Fogg

Yet he could live in his body for a thousand years if he escaped accident, homicide, or—here he crossed himself, since though an Eridanean he was also a devout Catholic—he killed himself. Why throw away a millennium by allowing himself to be sucked into the trap assuredly set by the rajah of Bundelcund? Was this not suicide, and was not suicide unforgivable? Would Fogg agree to this reasoning, this inescapable logic, if it were set before him?

Alas, he would not!

But perhaps the rajah had no intention of sending out a distorter wave. Perhaps he was sensible and was snoozing away at this very moment, no doubt in the soft arms and on the soft breasts of some beautiful houri or whatever the Hindus called their wives. That would be much more rational than sitting up late at night and sending out signals. But men, alas, were not always—or, in fact, were seldom—rational.

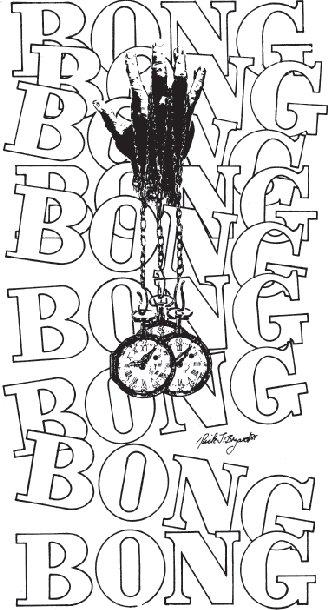

As if to affirm this conclusion, the watch emitted a ringing sound.

Passepartout jumped again, and his heart thumped as if it were a trampoline on which fear was performing. The dreaded had indeed happened!

For a second, Passepartout thought of keeping the news to himself. But, despite his terrors, he was a courageous man, and it was his duty to inform the Englishman. First, though, he must send the return signal.

As soon as the ringing stopped, he pushed down on the stem of the watch and quickly twisted it one hundred and eighty degrees to the right and then set the hands on the prescribed numbers. Immediately after, he returned the hands to the correct time—his correct time, anyway—and returned the stem to its original position. Then he hurried into the bungalow to wake Fogg up.

Fogg awoke easily and was on his feet at once. After listening to Passepartout’s excited whisperings, he said, “Very well. Now, here is what we shall do.”

Passepartout had been as pale as moonlight on still waters. Now his skin looked like that moonlight after it had been

passed through a bleach. But when Fogg was through talking, Passepartout obeyed at once. His first task was made easier because the Parsi was still sleeping soundly and soundily. His snores were terrible enough to frighten off a tiger. Passepartout led Kiouni away. When they were half a mile d own the southern slope of the mountain, the two men climbed up the rope ladder and rode him the rest of the way. Kiouni did not like being taken away from his feeding, but he did not trumpet. He went slowly because his eyes could not pick out obstacles easily in the moonlight. Also, he had to be careful about stepping into holes. The weight of the beasts is such that even a four-inch misstep may break their legs.

About an hour later, the two were at a distance which Fogg judged sufficient. Passepartout dismounted; Fogg remained on the elephant.

“But will not Sir Francis and the guide be able to hear the sounds even from here?” Passepartout said.

“Possibly,” Fogg said. “However, the mountain itself and much forest is between us. They should deaden the sounds. They may believe they are hearing a distant temple bell. In any event, there is nothing they can do about it. When we return, we shall tell them that the elephant ran away and we went after it.”

Passepartout shivered.

“When

we return...!”

It would be more realistic to say “if,” not “when.” Nevertheless, he admired the optimism of the Englishman and deeply hoped that it was not ill-founded.

During the journey, Passepartout had three times swiftly adjusted the watch to send out signals. The received signals were now coming every twenty seconds.

“Set it so it will go on

transmit

in five minutes from now,” Fogg said. “But make sure that its field is wide enough, since it must include Kiouni. And make sure that it will automatically go on

receive

five minutes after its transmit mode is terminated.”

Passepartout, his teeth chattering, opened the back cover of the watch and set it as directed, turning three tiny knobs. He placed the watch in a small hole he had dug in the ground with his knife. It was necessary that the device be below the ground level of those to be teleported. Also, the hole would keep the elephant from accidentally stepping on it if he should move, though Passepartout hoped that the beast would stand still. If he did take too many steps in any direction, he and his riders might find themselves cut in half.

He scrambled back up the rope ladder and pulled up the rope after him. He coiled it on the floor below one of the howdah seats. Mr. Fogg was already sitting on the neck of the beast. He had closely observed the command words and hand and touch signals used by the mahout. He used them now as if he had been in the profession for years. So far, the animal had obeyed him. Would it continue to do so when it suddenly found itself elsewhere and surrounded by hostile humans?

Passepartout, unable to consult his watch, mentally counted off the seconds. He was sitting on the saddle between the howdah seats, his unfolded jackknife in his hand. He felt pathetically helpless, and he wondered what the nine hundred and sixty years of life that he was throwing away would have been like. Ah, to see what 2842 A.D. held for him! Or even 1972! When the Eridaneans had exterminated the verminous Capelleans, then they could change the world. Would it take more than a hundred

years? Would not Earth be a paradise, a veritable Utopia, with all war, crime, poverty, disease, and hatred wiped out forever? Why should he be denied the fruits of his labor because of this madman whose placid back was now before him?

But if a cause is to win, it must do so over the bodies of martyrs, as someone, probably an Englishman, had once said. It was his misfortune to be one of those martyrs. Still, a martyr should not sacrifice himself unless the cause could profit by it. There would be no profit to anybody tonight except the rajah of Bundelcund.

Yet, had not Fogg said that, for him, the unforeseen did not exist?

But what if he had foreseen that the rajah would die but they would die too?

No, Fogg was a gentleman, and he did have a kind heart. He would not ask his servant, and his colleague, to be killed also. Not unless it was necessary, Passepartout thought, his heart drooping now like a flag on a breezeless day. But what could they do with only small knives against rifles and spears?

“Ah,

mon

...”

And they were there “...

Dieu!

”

Fogg had not been as blind as Passepartout had thought. A spy had long ago managed to report where and in what manner the distorter was located and guarded. Fogg had not told Passepartout about this simply because he was not sure that the situation had not changed since the report. It would not do to have Passepartout all set for one environment and suddenly be faced with the unexpected. It might throw him too much off balance. The poor fellow was in a state of terror as it was.

Indeed, Fogg would have left him behind if he had not been sure that Passepartout would be thoroughly capable once the action began. No genuine coward would have survived to the age of forty in this secret war. Nor would Stuart have entrusted his mission to anybody who had not proved himself many times over. To fear is not to lack courage.

His main concern was the behavior of Kiouni. His training as a war elephant was only half-completed. Even a seasoned old veteran might go into hysterics.

The transit was made instantaneously. There was no sense whatsoever of passage through time or distance. Their ears were battered with a great clanging as if they were standing a few inches below a bell as large as the bungalow. Its sound was shattering, and Fogg and his aide, though holding the jack-knives with their fingers, had to thrust the ends of their thumbs into their ears.

Kiouni bolted; his trunk was raised and he was, seemingly, shrilling panic through it. He could not be heard above the hideous clanging, which, as always, tolled nine times. This auditory phenomenon accompanied the operation of a distorter at both the receiving and transmitting ends. The site of the watch they had left behind would be loud with nine clangs, loud enough to carry faintly to Sir Francis and the Parsi even with some miles of mountain and forest deadening it.

The theory accounting for the noises was that the distortion of the space in the area around the devices caused a condensation and bending of the electromagnetic field of the Earth itself. The return to a normal state resulted in atmospheric disturbance and consequent clangings. This theory was disputed, but it did not matter what made the noises. They were unavoidable and, unfortunately, acted as an alarm.

Fogg saw at a glance that the rajah had not moved the distorter since the report. Its location was something that only an Oriental would dream up.

They were in a vast room lit by thousands of gas jets. It soared perhaps six stories, ending in a great white dome. The room itself was circular with a diameter of perhaps two hundred yards. Its circumference was set with over three hundred tall and narrow archways—a quick estimate—with a mosaic walk about ten feet wide inside it. This ran completely around the chamber. The walk was set about an inch above the level of the great pool that constituted most of the surface level of the place. The floor was mostly a body of water, and in its center was a circular islet of smooth red marble. This had a diameter of forty feet. Kiouni and his riders had appeared in its exact center, though they did not stay there long.

Kiouni had begun running madly almost at once around and around the edge of the islet. Elephants are splendid swimmers, but even in his panic he had not cared to plunge into the water. The reason, Fogg perceived as he rode around and around, was the large number of large crocodiles in the pool.

Fogg set himself to calming the beast. While engaged in this seemingly hopeless business, he felt a tap on his shoulder. He looked back and then upward. Passepartout was pointing at the ceiling. Fogg saw a square of blackness appearing in the center of the white dome. From it, suspended on a cable, a car was descending. Six dark faces topped by white turbans stared over the sides of the car.

Fogg looked at the archways around the walk. They were still empty.

Passepartout then pointed at the center of the islet. He indicated what they had missed before because the bulk of the elephant had been between the rajah’s distorter and the two men, and both had been too occupied since to look for it.

The device must have been set in the circular depression in the center of the islet. Certainly, it had not just been placed in the hole so the newcomer merely had to stoop over to pick it up. It would be placed within a defense of some kind. What alarmed Passepartout was that the distorter, contained in a watch, was disappearing. It had been placed on top of a cylinder set about an inch below the level of the islet’s surface. Now the cylinder was sinking swiftly into the shaft.

The islet must be hollow with a room beneath the surface. Men below were operating the machinery which raised and lowered the cylinder of stone. They would remove the device from the top of the cylinder and take it to a safe place. Then the rajah’s men would take care of the intruders.

Kiouni had not slowed down in his circular dash. There was no more time for endeavoring to control him. Fogg gestured at Passepartout to take his place, and he rolled off the neck of the beast. His agility would have drawn applause from the professional acrobat, Passepartout, under different circumstances. But the Frenchman was too busy hanging on.

As Fogg slid down the gray wrinkled side, he pushed himself away, landed facing the elephant’s side, fell back, but kept on walking backwards and so saved himself a hard fall on the marble. Whirling then, he yanked from a vest pocket a

watch, twisted its stem, looked down into the hole, and dropped the watch. From first to last, despite his swiftness, he managed to perform with an air of unhurriedness, of perfect aplomb.

The men above him and the men below may have, undoubtedly did, cry out. He could not have heard them since his ears were still ringing. But he did look up and saw, not unexpectedly, that five in the car were brandishing sabers and one was holding a rifle. This looked like a modern rifle, perhaps the Mauser adopted by the Prussian army only the year before. Those in the car could see that the invaders had no firearms. Since no smoke had resulted from his dropping of an object into the shaft, they must have believed that, if it were a bomb, it had failed to go off. Possibly, they had not seen him drop the watch, since his body had been between them and the shaft. Nor would they believe they had to shoot the intruders; they were trapped. They could take their time, dispose of the elephant if it failed to calm down, and overpower the men. Meanwhile, the rajah would have retrieved the distorter in the room.

Fogg believed that the rajah was down there, since it was unlikely that he would allow anyone but himself to handle the invaluable device. In fact, Fogg was certain that there was only one man below, the rajah. The fewer who saw the distorter, the better. It would be, in the eyes of the Hindus, a magical device, one that many would do anything to possess.

Mr. Fogg turned, having extracted and set another watch. With a smooth motion, he tossed it upward into the car, which was now about two and a half stories above the islet. The actions of those he could see became very agitated. Two dived out of the car into the pool. The car disappeared in a spurt of flame

surrounded by smoke. The blast was dimly heard by the two men and Kiouni, but they felt it as if it were a giant hand slapping them. Bits of thin steel and flesh and bone rained over them.