Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind (28 page)

Read Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind Online

Authors: V. S. Ramachandran,Sandra Blakeslee

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

Brahman is all. From Brahman come appearances, sensations, desires, deeds. But all these are merely name

and form. To know Brahman one must experience the identity between him and the Self, or Brahman dwelling

within the lotus of the heart. Only by so doing can man escape from sorrow and death and become one with

the subtle essence beyond all knowledge.

—Upanishads,

500 b.c.

"The Unbearable Lightness

of Being"

"One can't believe impossible things." "I daresay you haven't had much practice, " said the Queen. "When I

was your age I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible

things before breakfast. "

—

Lewis Carroll,

Through the Looking Glass

"As a rule, " said Holmes, "the more bizarre a thing is the less mysterious it proves to be. It is your

commonplace, featureless crimes which are really puzzling, just as a commonplace face is the most difficult to

identify. "

—

Sherlock Holmes

I'll never forget the frustration and despair in the voice at the other end of the telephone. The call came early one afternoon as I stood over my desk, riffling through papers looking for a misplaced letter, and it took me a few seconds to register what this man was saying. He introduced himself as a former diplomat from Venezuela whose son was suffering from a terrible, cruel delusion. Could I help?

"What sort of delusion?" I asked.

His reply and the emotional strain in his voice caught me by surprise. "My thirty−year−old son thinks that I am not his father, that I am an impostor. He says the same thing about his mother, that we are not his real parents." He paused to let this sink in. "We just don't know what to do or where to go for help. Your name was given to us by a psychiatrist in Boston. So far no one has been able to help us, to find a way to make Arthur better." He was almost in tears. "Dr. Ramachandran, we love our son and would go to the ends of the earth to help him. Is there any way you could see him?"

"Of course, I'll see him," I said. "When can you bring him in?"

Two days later, Arthur came to our laboratory for the first time in what would turn into a yearlong study of his condition. He was a good−looking fellow, dressed in jeans, a white T−shirt and moccasins. In his mannerisms, he was shy and almost childlike, often whispering his answers to questions or looking wide−eyed at us.

113

Sometimes I could scarcely hear his voice over the background whir of air conditioners and computers.

The parents explained that Arthur had been in a near−fatal automobile accident while he was attending school in Santa Barbara. His head hit the windshield with such crushing force that he lay in a coma for three weeks, his survival by no means assured. But when he finally awoke and began intensive rehabilitative therapy, everyone's hopes soared. Arthur gradually learned to talk and walk, recalled the past and seemed, to all outward appearances, to be back to normal. He just had this one incredible delusion about his parents—that they were impostors—and nothing could convince him otherwise.

After a brief conversation to warm things up and put Arthur at ease, I asked, "Arthur, who brought you to the hospital?"

"That guy in the waiting room," Arthur replied. "He's the old gentleman who's been taking care of me."

"You mean your father?"

"No, no, doctor. That guy isn't my father. He just looks like him. He's—what do you call it?—an impostor, I guess. But I don't think he means any harm."

"Arthur, why do you think he's an impostor? What gives you that impression?"

He gave me a patient look—as if to say, how could I not see the obvious—and said, "Yes, he looks exactly like my father but he

really

isn't. He's a nice guy, doctor, but he certainly isn't my father!"

"But, Arthur, why is this man pretending to be your father?"

Arthur seemed sad and resigned when he said, "That is what is so surprising, doctor. Why should anyone want to pretend to be my father?" He looked confused as he searched for a plausible explanation. "Maybe my real father employed him to take care of me, paid him some money so that he could pay my bills."

Later, in my office, Arthur's parents added another twist to the mystery. Apparently their son did not treat either of them as impostors when

they spoke to him over the telephone. He only claimed they were impostors when they met and spoke face−to−face. This implied that Arthur did not have amnesia with regard to his parents and that he was not simply "crazy." For, if that were true, why would he be normal when listening to them on the telephone and delusional regarding his parents' identities only when he looked at them?

"It's so upsetting," Arthur's father said. "He recognizes all sorts of people he knew in the past, including his college roommates, his best friend from childhood and his former girlfriends. He doesn't say that any of them is an impostor. He seems to have some gripe against his mother and me."

I felt deeply sorry for Ardiur's parents. We could probe their son's brain and try to shed light on his condition—and perhaps comfort them with a logical explanation for his curious behavior—but there was scant hope for an effective treatment. This sort of neurological condition is usually permanent. But I was pleasandy surprised one Saturday morning when Arthur's father called me, excited about an idea he'd gotten from watching a television program on phantom limbs in which I demonstrated that the brain can be tricked by simply using a mirror. "Dr. Ramachandran," he said, "if you can trick a person into thinking that his paralyzed phantom can move again, why can't we use a similar trick to help Arthur get rid of his delusion?"

114

Indeed, why not? The next day, Arthur's father entered his son's bedroom and announced cheerfully, "Arthur, guess what! That man you've been living with all these days is an impostor. He really isn't your father. You were right all along. So I have sent him away to China. I am your real father." He moved over to Arthur's side and clapped him on the shoulder. "It's good to see you, son!"

Arthur blinked hard at the news but seemed to accept it at face value. When he came to our laboratory the next day I said, "Who's that man who brought you in today?"

"That's my real father."

"Who was taking care of you last week?"

"Oh," said Arthur, "that guy has gone back to China. He looks similar to my father, but he's gone now."

When I spoke to Arthur's father on the phone later that afternoon, he confirmed that Arthur now called him

"Father," but that Arthur still seemed to feel that something was amiss. "I think he accepts me intellectually, doctor, but not emotionally," he said. "When I hug him, there's no warmth."

Alas, even this intellectual acceptance of his parents did not last. One week later Arthur reverted to his original delusion, claiming that the impostor had returned.

Arthur was suffering from Capgras' delusion, one of the rarest and most colorful syndromes in neurology.1

The patient, who is often mentally quite lucid, comes to regard close acquaintances—usually his parents, children, spouse or siblings—as impostors. As Arthur said over and over, "That man looks identical to my father but he really isn't my father. That woman who claims to be my mother? She's lying. She looks just like my mom but it isn't her." Although such bizarre delusions can crop up in psychotic states, over a third of the documented cases of Capgras' syndrome have occurred in conjunction with traumatic brain lesions, like the head injury that Arthur suffered in his automobile accident. This suggests to me that the syndrome has an organic basis. But because a majority of Capgras' patients appear to develop this delusion "spontaneously,"

they are usually dispatched to psychiatrists, who tend to favor a Freudian explanation of the disorder.

In this view, all of us so−called normal people as children are sexually attracted to our parents. Thus every male wants to make love to his mother and comes to regard his father as a sexual rival (Oedipus led the way), and every female has lifelong deep−seated sexual obsessions over her father (the Electra complex). Although these forbidden feelings become fully repressed by adulthood, they remain dormant, like deeply buried embers after a fire has been extinguished. Then, many psychiatrists argue, along comes a blow to the head (or some other unrecognized release mechanism) and the repressed sexuality toward a mother or father comes flaming to the surface. The patient finds himself suddenly and inexplicably sexually attracted to his parents and therefore says to himself, "My God! If this is my mother, how come I'm attracted to her?" Perhaps the only way he can preserve some semblance of sanity is to say to himself, "This must be some other, strange woman." Likewise, "I could never feel this kind of sexual jealousy toward my real dad, so this man must be an impostor."

This explanation is ingenious, as indeed most Freudian explanations are, but then I came across a Capgras'

patient who had similar delusions about his pet poodle: The Fifi before him was an impostor; the real Fifi was living in Brooklyn. In my view that case demolished the Freudian explanation for Capgras' syndrome. There may be some latent bestiality in all of us, but I suspect this is not Arthur's problem.

115

A better approach for studying Capgras' syndrome involves taking a closer look at neuroanatomy, specifically at pathways concerned with visual recognition and emotions in the brain. Recall that the temporal lobes contain regions that specialize in face and object recognition (the what pathway described in Chapter 4). We know this because when specific portions of the what pathway are damaged, patients lose the ability to recognize faces,2 even those of close friends and relatives—as immortalized by Oliver Sacks in his book

The

Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

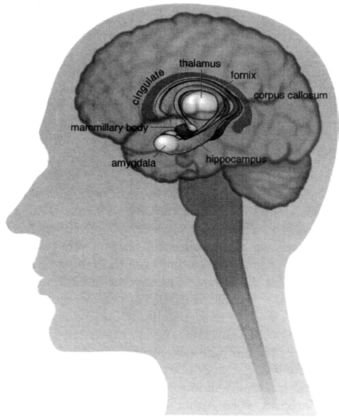

In a normal brain, these face recognition areas (found on both sides of the brain) relay information to the limbic system, found deep in the middle of the brain, which then helps generate emotional responses to particular faces (Figure 8.1). I may feel love when I see my mother's face, anger when I see the face of a boss or a sexual rival or deliberate indifference upon seeing the visage of a friend who has betrayed me and has not yet earned my forgiveness. In each instance, when I look at the face, my temporal cortex recognizes the image—mother, boss, friend—and passes on the information to my amygdala (a gateway to the limbic system) to discern the emotional significance of that face. When this activation is then relayed to the rest of my limbic system, I start experiencing the nuances of emotion—love, anger, disappointment—appropriate to that particular face. The actual sequence of events is undoubtedly much more complex, but this caricature captures the gist of it.

After thinking about Arthur's symptoms, it occurred to me that his strange behavior might have resulted from a disconnection between these two areas (one concerned with recognition and the other with emotions).

Maybe Arthur's face recognition pathway was still completely normal, and that was why he could identify everyone, including his mother and father, but the connections between this "face region" and his amygdala had been selectively damaged. If that were the case, Arthur would recognize his parents but would not experience any emotions when looking at their faces. He would not feel a "warm glow" when looking at his beloved mother, so when he sees her he says to himself, "If this is my mother, why doesn't her presence make me

feel

like I'm with my mother?" Perhaps his only escape from this dilemma—the only sensible interpretation he could make given the peculiar disconnection between the two regions of his brain—is to assume that this woman merely resembles Mom. She must be an impostor.3

116

Figure 8.1

The limbic system is concerned with emotions. It consists of a number of nuclei (cell clusters)

interconnected by long @−shaped fiber tracts. The amygdala

—

in the front pole of the temporal

lobe

—

receives input from the sensory areas and sends messages to the rest of the limbic system to produce

emotional arousal. Eventually, this activity cascades into the hypothalamus and from there to the autonomic

nervous system, preparing the animal (or person) for action.

Now, this is an intriguing idea, but how does one go about testing it? As complex as the challenge seems, psychologists have found a rather simple way to measure emotional responses to faces, objects, scenes and events encountered in daily life. To understand how this works, you need to know something about the autonomic nervous system—a part of your brain that controls the involuntary, seemingly automatic activities of organs, blood vessels, glands and many other tissues in your body. When you are emotionally aroused—say, by a menacing or sexually alluring

face—the information travels from your face recognition region to your limbic system and then to a tiny cluster of cells in the hypothalamus, a kind of command center for the autonomic nervous system. Nerve fibers extend from the hypothalamus to the heart, muscles and even other parts of the brain, helping to prepare your body to take appropriate action in response to that particular face. Whether you are going to fight, flee or mate, your blood pressure will rise and your heart will start beating faster to deliver more oxygen to your tissues. At the same time, you start sweating, not only to dissipate the heat building up in your muscles but to give your sweaty palms a better grip on a tree branch, a weapon or an enemy's throat.