Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) (8 page)

Read Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: James Baikie

Tags: #History

Now we turn to the right up the Vicus Tuscus towards the Forum Romanum, the centre of the city's life. As we pass along the street we meet a constant stream of wayfarers, while an equally constant stream flows in the same direction as that in which we are going. Here is a senator, looking down with supreme contempt on the plebeian crowd, as he passes in his litter, borne high on the shoulders of his slaves, towards the Forum. Behind him follows a perfect crowd of his retainers and hangers-on, who live on the pickings that he flings to them, and shout for him in public, and do all his dirty work in private.

Here comes another litter, more gorgeous still. In old times it would have been closed, for a Roman matron of the great days of the Republic kept herself very much to herself. It was her glory that she "stayed at home and spun wool," and when she was obliged to go abroad she went as quietly and unobtrusively as possible. But times are changed, and the Roman ladies go everywhere, have a voice in every question and a finger in every mischief, and pride themselves on drawing the gaze of every eye when they parade their splendours through the city. So Julia, or Sempronia, or whoever she may be, sits unabashed in her open litter, her arms and fingers glittering with gold and jewels, her very sandals flashing with precious stones, the picture of insolent pride. I wonder how many blows and tears that magnificent toilet of hers, and that miraculous piece of hair-dressing that crowns her head, cost her poor slaves this morning. For a proud Roman dame would never deign to exchange words with such cattle as her slaves; a sign with the finger is the utmost condescension by which she will reveal her will, and if she is misunderstood, the lash is the least reward for the poor waiting-woman's blunder.

Take care how you tread, for this street is absolutely the worst paved way in Rome. The contract for it was given to Verres, that rascal whom Cicero prosecuted for his cruelty and swindling in Sicily; and he cheated the city over it, as he always did. In fact, it is so bad that Verres himself never would walk over it, but always preferred to go round by another way. Look at that fellow going past swathed in a long white robe of the finest Egyptian linen. The shaven head, the thin bronzed features, and the furtive look tell you that he is a priest of Isis, the great Egyptian goddess whose worship has become so popular in Rome of late. The priests of Isis are men to be on your guard against, for all the superstition and wickedness of Rome have drawn to this strange Oriental faith, and if there is any mischief stirring in the city, it will be strange if you do not find a priest of Isis at the centre of it.

But now we have reached the Forum. Look around well, for nowhere in the world will you see so much splendour and wealth. On your right hand, as we pass into the corner of the Forum, stands the temple of Castor and Pollux, built on the very site of the spring where the great Twin Brethren watered their horses as they rode in with the news of the victory at Lake Regillus. Splendid as it is, however, it is completely dwarfed by the huge building on the left. This is the great Court-House, the Basilica Julia, begun by Julius Cæsar and completed by Augustus. If you can squeeze in through the crowd (for a famous case is being heard), you will see the eighty judges seated on the bench, all the most famous lawyers of the Empire arrayed on either side beneath, for prosecution or defence, and the vast hall and galleries packed almost to suffocation with interested spectators.

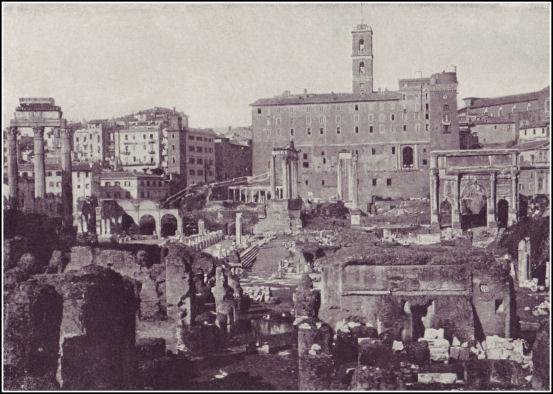

THE ROMAN FORUM

Close beside you, as you stand between the Temple of the Twins and the Basilica, is the spot where one of the darkest tragedies of Roman history befell. Here, in early days, stood a line of butcher's stalls, and it was from one of these stalls that Virginius snatched the knife wherewith he struck his fair young daughter Virginia to the heart, when nothing else could save her from slavery and shame. On your left hand, enclosed by a marble balustrade, is another spot sacred in the ancient traditions of Rome. For it is written that in the days of old a great chasm opened in the midst of the Forum, and could by no means be filled up; and when the counsel of the gods was sought, answer was given that the chasm would never close until what was most precious in Rome was cast into it. Then some were for throwing one rich treasure, and some another, into the gulf, but all to no avail; when at last Marcus Curtius, a noble Roman youth, dressed himself in full armour, mounted his charger, and crying that the most precious thing in Rome was the life of its youth, spurred his steed across the Forum and leaped, horse and man, into the dark abyss. And forthwith the gulf closed, and great awe fell upon all who beheld, and the place is held sacred even unto this day.

Turn now to your left and look towards the western end of the Forum, past the Lacus Curtius, as it is called, and the great pillars that adorn the square. Behind all, and closing the view to the west, towers the Capitoline hill, bearing on its southern spur a group of splendid buildings, the Temple of Concord, the Temple of our new Emperor Vespasian, the Portico of the Twelve Gods, the solid masonry of the Public Record Office, and, dominating and crowning everything, the superb Temple of Jupiter of the Capitol, the Father-God of Rome. There, on the northern spur of the hill, is the ancient citadel of Rome, and beside it the Temple of Juno Moneta, where the coinage is struck, and whence the word Mint shall be used henceforth as the name of all such places. On the gloomy rock face of this spur is the Tullianum, the horrible prison where offenders against the State languish out their lives, or die swift and violent deaths.

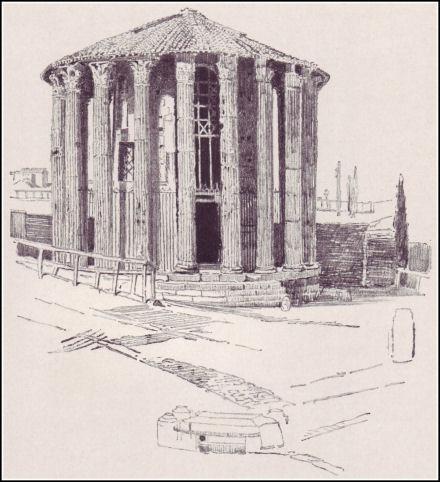

TEMPLE OF MATER MATUTA

Beneath the Capitoline, and just behind the Forum, stands the beautiful Temple of Saturn. And here, right across the western end of the square, runs a marble balustrade and terrace, decorated along its face with the brazen beaks of captured galleys. This platform is the famous Rostra, from which the leaders of Rome address the gatherings of the people in time of stress and excitement. Many a time the Forum has rung with the winged words spoken by men like Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, or later by Cicero and his rival orator Hortensius, from this famous terrace. Nor has it been without its tragedies, as well as its triumphs of oratory. Here were exposed the severed heads of the victims in those mad welters of bloodshed that marked the successive supremacies of Marius and Sulla, and here the head and hands of Marcus Tullius Cicero, supreme of all speakers who have used the Latin tongue, were nailed, by order of his slayer, Mark Antony, to the balustrade that had echoed to his great orations. It suggests what Roman manhood and womanhood had fallen to in those days when one remembers that a soldier like Antony thus derided his fallen foe, and that Antony's wife Fulvia came forward to the Rostra, looked scornfully upon the dead face, and then, drawing a golden hairpin from her headdress, thrust it through the tongue that had once been so eloquent in the cause of Rome.

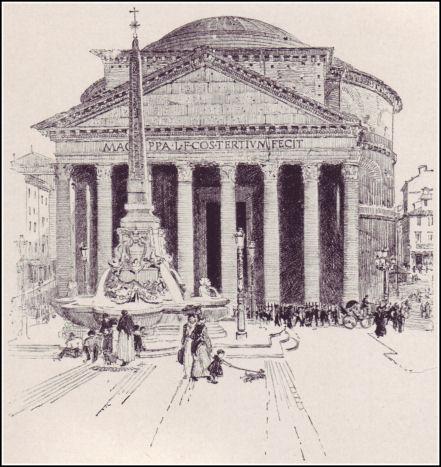

THE PANTHEON

At the south end of the Rostra stands an inconspicuous stone, which yet has its own interest; for this is the Golden Milestone, and from it all the roads of the world are measured. The curious column at the other end of the terrace is an old and famous memorial. It is the Duilian Column, erected to commemorate the great victory won by our old friend Gaius Duilius (him who was always to be accompanied by flute-players) over the Carthaginian fleet at Mylæ; and these ugly monsters projecting from it are the rams of the Carthaginian galleys captured in that great victory.

Glance now along the north side of the Forum before we turn homewards again. Standing back a little from the open square is the Senate House. It has no very special interest, for it is comparatively new-at least, it is only 120 years old. The famous old building which had heard all the debates and witnessed all the triumphs and tragedies of 500 years, which had seen all heads bowed when the news of the dreadful slaughter of Cannæ arrived, and had echoed to the shouts of joy that hailed the victory of Zama, was burned in 52 B.C. during a riot which rose over the funeral of that most abandoned scamp, Publius Clodius. Apart from its memories, the old building had not much to commend it. It was the chilliest place in Rome, for even in mid-winter there was no means of heating it, and the stately senators sat and shivered, with chattering teeth and red noses, no matter how warm the debate might wax. On one bitter January day in Cicero's time, the cold was so unbearable that the Speaker had to dismiss the Senate, and it is sad to have to tell that the vulgar crowd in the Forum, instead of sympathizing with the chilly legislators, laughed and jeered at their blue pinched faces and shaking hands. The new building is more comfortable than the old, but the glory has departed, though the comfort has increased. Nobody cares now what the Senate may say or do.

In front of the Senate House lies a slab of black marble, guarded by two lion-crowned piers, and fronted by an altar. The famous "Black Stone" of Rome is one of its most sacred relics, for here, as our fathers have told us, lie that which was mortal of Romulus, who founded the city, since that day when he himself was translated to heaven, and became one with the gods. East of the Senate House is the little Temple of Janus, the two-faced god, whose gates may never be shut save when Rome is at peace with all the world. Beyond it runs the Argiletum, the booksellers' street of Rome, where all the book-fanciers come to buy the costly rolls of parchment that make libraries the luxury of the few and wealthy. Another stately Court-House, the Basilica Æmilia, completes the circuit of the Forum.

Perhaps we have seen enough for one day. At all events, we have been at the heart of Rome, and we have seen more splendours crowded and heaped together than we are ever likely to see in any other spot of equal size in all the world. Besides, if we are to see the Triumph of Vespasian and Titus, which will take place in a few days, we need not weary ourselves out beforehand with sight-seeing. So we leave the Forum, with all its memories of glory and disaster, heroism and shame, and, passing along the Sacred Way, we stroll eastwards home to the house of Publius on the Esquiline.

The Triumph

N

OW

we are to have the chance of seeing the most splendid sight that even the Eternal City can ever show us. For you must know that the Romans, a race of soldiers, had decreed for their victorious generals the privilege of passing in triumph with their armies through the city, on their return from the wars. Only, as was most meet, this honour, which was the highest Rome could give, was most jealously guarded; nor was it bestowed for trifling feats of war, until in later days some of the emperors, mad with pride, dishonoured it to be the plaything of their own folly. Thus, Caligula celebrated a triumph for having made the legions gather shells on the shores of the Channel, and Nero because he had gained a prize at the Olympic Games by singing on the public stage. But for a real triumph the conditions were severe. The victor must have commanded independently through the campaign. He must have been victorious in all his battles, and pressed every advantage to its utmost; and he must have led his victorious army safely home. Above all, a true mark of the bloodthirsty Roman, his army must have slain, in a single battle, at least 5,000 of the enemy.