Pediatric Examination and Board Review (135 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

10.

(A)

Osteochondritis dissecans injuries are much more common in the skeletally immature athlete; however, they are more frequently associated with overuse (see

Figure 79-3

). Boys in the second decade of life are most affected. The etiology is multifactorial and thought to result from cumulative microtrauma to the subchondral bone leading to stress fracture and, ultimately, collapse. The child often presents with mild to moderate chronic pain that is associated with activity. Treatment of this lesion depends on whether the cartilage is intact, partially attached, or completely detached.

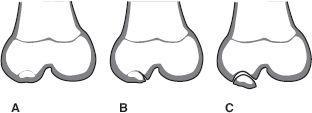

FIGURE 79-3.

Various forms of the osteochondritis dissecans lesion found in children.

A.

Defect in ossification center without cartilage defect.

B.

Lesion with a hinged flap.

C.

Complete separation of bone and cartilage, which can lead to loose body in the knee joint. (Reproduced, with permission, from Skinner HB. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006: Fig. 11-27.)

11.

(A)

It is reasonable to assume that a 12-year-old girl is not yet skeletally mature. Therefore, the highest risk of injury associated with knee trauma is a physeal injury to the distal femur or proximal tibia. Physeal, or growth plate injuries are best treated with casting and crutches and merit a referral to a pediatric orthopedist because there is increased risk of growth arrest. Tibial tubercle avulsion injuries can best be diagnosed on a lateral radiograph of the knee and also merit an orthopedic evaluation. ACL injuries do occur in skeletally immature athletes. The management of ACL injuries at this age is controversial. In the setting of physeal injuries, a number of nondisplaced Salter-Harris 1-2 fractures can be difficult to see on plain radiographs. Often a follow-up radiograph obtained 24-48 hours postinjury or 10-14 days postinjury will demonstrate the fracture line or a periosteal reaction. MRI, CT, and bone scan are all sensitive and specific for identifying physeal fractures. Clinically, pain at the end of long bones is a physeal injury until proven otherwise.

12.

(B)

Osteochondritis dissecans lesions are most common in boys 9-18 years old. Patellofemoral pain and patellar dislocations are associated with underlying patellar instability and malalignment, a clinical finding more common in females. Females tend to have valgus knee alignment that is often associated with flat feet. These cause overpronation and abnormal patellar tracking on the femur. Females often have “looser” ligaments and relatively weaker supporting muscles such as the quadriceps and hamstring muscles. ACL injuries are more common in females because of the above factors and the frequent presence of a smaller bony notch on the femur for the ligament to pass through. Hormonal influences are also thought to play a role in increasing a female’s risk of ACL injury.

13.

(B)

Osgood-Schlatter disease is inflammation and pain at the tibial tubercle seen in growing prepubescents (see

Figure 79-4

). It results from repetitive microscopic injuries that produce inflammation of the apophysis of the tibial tuberosity and partial avulsion of the tibial tubercle. Patellofemoral pain syndrome is the most common cause of adolescent knee pain, particularly in females. It is often referred to as anterior knee pain. There are many contributing factors (see next question). Plica syndrome is a painful band of synovial tissue that snaps on the undersurface of the patella causing pain. Iliotibial band syndrome is tendonitis causing lateral knee pain—most common in runners.

FIGURE 79-4.

Osgood-Schlatter disease. The radiographs would show characteristic fragmentation of the tibial tubercle apophysis, similar to that shown in the diagram. (Reproduced, with permission, from Skinner HB. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006: Fig. 11-29.)

14.

(C)

Anterior or patellofemoral pain is associated with a variety of physical findings including flat feet, knock knees (valgus knees), and increased internal hip rotation (femoral anteversion). Obesity also contributes to the presence of anterior knee pain. Functionally, weak quadriceps muscles, tight hamstrings, and patellar instability contribute to the development of patellofemoral pain. The Q angle refers to the relationship of the quadriceps and patella vectors. One line is drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine and bisects the mid-superior pole of the patella. A second line is drawn from the mid-patella to the mid-patellar tendon. An angle more than 20 degrees is associated with lateral patellar tracking and increased stress on the patellofemoral joint.

15.

(E)

Patellofemoral pain has often been referred to as “theater knee” because weight-bearing activities and prolonged sitting tend to increase anterior knee pain. Sitting with the knee extended or performing exercises with a straight leg do not require stress to be placed across the patellofemoral joint, therefore usually do not hurt, and are often used as early exercises to start strengthening the leg without aggravating the patella and its surrounding structures.

16.

(D)

Obese and rapidly growing adolescent boys are at highest risk for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). There is often no associated trauma. Symptoms are often gradual but can be acute in onset. Pain is noted as well as limited range of motion. The typical “ice cream falling off the cone” is noted on AP and frog leg films of the hip. An irregular widening of the epiphyseal line is seen and the epiphysis is displaced downward and posterior. Emergent referral to an orthopedic surgeon is needed.

17.

(E)

The most likely diagnosis for this child is Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, an avascular necrosis of the femoral head. This is most commonly seen in elementary school age children, more often boys. Often an injury precedes the symptoms and the initial radiographs are normal.

S

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Bernstein J.

Musculoskeletal Medicine

. Rosemont, IL: AAOS Publications; 2003.

Fleisher GR.

Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2010.

Harris SS, Anderson SJ.

Care of the Young Athlete.

2nd ed. Rosemont, IL: AAOS and AAP Publications; 2009.

CASE 80: A 15-YEAR-OLD AND A 17-YEAR-OLD WHO COLLAPSE DURING A MARATHON

You are working in the emergency department on a Saturday afternoon watching the local marathon race on television. The announcer has just stated that the outside temperature is 95°F (35°C) and the humidity is 80%.

A 15-year-old female marathon runner is brought into the emergency department complaining of spasms in her calf muscles, mild lower abdominal pain, and thirst. She states she is competing in her first marathon, softball is her usual sport, and she didn’t train much for this race. She did drink some water every 3 miles at the fluid stations then collapsed at mile 16. Her weight is 85 kg. Her vital signs are: pulse 96 bpm, blood pressure (BP) 110/70 mm Hg, respiratory rate 28, temperature 99.9°F (37.7°C). She is wearing a tight-fitting, dark long-sleeve shirt over a tank top and matching shorts. Upon removal of her garments she was noted to have sunburned skin without blistering on her face, back, chest, and upper and lower extremities. She appears profusely sweaty and has tight gastrocnemius muscles with spasms.

SELECT THE ONE BEST ANSWER

1.

Which diagnosis most likely explains this athlete’s symptoms?

(A) sunburn

(B) dehydration

(C) heat exhaustion

(D) heat cramps

(E) heat stroke

2.

Which of these factors contributed the most to this girl’s illness?

(A) obesity

(B) dehydration

(C) clothing

(D) sunburn

(E) excessive exercise

3.

What is the best initial treatment for this 15-year-old?

(A) intravenous (IV) fluid replacement with normal saline

(B) salt tablets

(C) unlimited oral intake of a standard electrolyte solution

(D) unlimited oral intake of water