Paul Revere's Ride (60 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

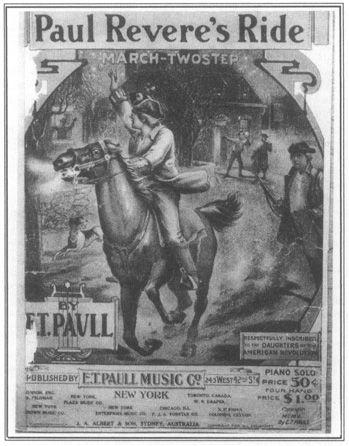

The interpretative mood in this era was also captured by a piece of music titled “Paul Revere’s Ride; a March-Two Step,” published in 1905 by E. T. Paull, a prolific composer of popular music. This musical version of the midnight ride began with the faint hoofbeats of a galloping horse. It advanced through movements that the composer called the “The Cry of Alarm,” “The Patriots Aroused,” “The Call to Arms” (double fortissimo), the Battle of Lexington and Concord (triple fortissimo), and “The Enemy Routed” (quadruple fortissimo). The piece was advertised as “one of E. T. Paull’s greatest marches,” no modest claim for the composer of “The Burning of Rome” and “Napoleon’s Last Charge.” His rendition of the midnight ride was “respectfully inscribed to the Daughters of the American Revolution.”

24

In Boston, the Daughters of the American Revolution actively promoted the reputation of Paul Revere. They took an active part in the rescue and preservation of Paul Revere’s home, which had become a rundown tenement in Boston’s North End. To preserve it, a voluntary society was founded with the name of the Paul Revere Memorial Association. It acquired title to the house, restored it with high enthusiasm, and opened it to the public in 1908 as a shrine of the Revolution. Today, the Paul Revere House is the only 17th-century building that survives in what was Old Boston.

25

In 1891, the first full-length biography of Paul Revere was published by Elbridge Henry Goss, a Boston antiquarian. It was a classic specimen of a two-volume Victorian “Life and Letters” biography, mainly a compendium of primary materials in two thick volumes, handsomely embellished with many illustrations and facsimiles. Goss was mostly interested in his subject as Colonel Revere, a political and military figure. Nearly 100 pages (of 622 in

the two volumes together) were devoted to the Penobscot Expedition alone. Very little attention was given to Revere’s private life.

The Filiopietists in Full Cry. This musical version of the militant Paul Revere had a grand crescendo scored quadruple fortissimo. (Brandeis University Library)

The major contribution of the work was to assemble and reprint primary evidence of Revere’s public life. Goss was given access to Revere manuscripts by the family. He published for the first time many letters and documents, including Revere’s deposition on the midnight ride, and also collected much colorful testimony from Boston families who preserved the folklore of the event. Every subsequent student of Revere’s life is heavily in Goss’s debt for the materials that he collected. Wherever possible, the author allowed Paul Revere to speak for himself. His chapter on the midnight ride consisted entirely of a transcription of Revere’s fullest account, with explanatory footnotes.

26

The larger purpose of the book was to celebrate Paul Revere’s qualities of character, as one of Boston’s “truest, most noble and patriotic sons.” In 1891, Elbridge Goss expressed a complete confidence that Revere’s reputation would continue to grow. “As time goes on,” he wrote, “such lives as his will be studied, honored, cherished and remembered with still greater reverence.”

27

U.S. v. The Spirit of ‘76: Paul Revere and the American Anglophiles

U.S. v. The Spirit of ‘76: Paul Revere and the American Anglophiles

Goss’s prediction proved to be right in one way, but wrong in another. Revere continued to be studied, but not always with “greater reverence.” In the 20th century, strong countervailing tendencies also began to appear. One of them was a new sympathy in the United States for the British side of the American Revolution. The late 19th century was a moment of Anglo-American rapprochement, when writers on both sides of the Atlantic suddenly discovered a sense of solidarity among the “Anglo-Saxon” nations. One result in academic scholarship was the “imperial school” of George Louis Beer and Charles Maclean Andrews, who rewrote early American history from the perspective of London and the Empire. Another was a circle of antiquarians who included Elizabeth Ellery Dana, Charles Knowles Bolton, and especially William Clements (1861-1934), a wealthy Michigan industrialist, and Harold Murdock (1862-1934), a prominent Boston banker.

This circle of American Anglophiles studied the outbreak of the Revolution as an Anglo-Saxon Civil War. They searched British homes and archives and unearthed many new primary sources on the Revolution, which they purchased from their impoverished owners and carried home in triumph to the United States. At the same time they also contributed many secondary studies, laboring to explode the patriot myths of American innocence on the one hand and British oppression on the other.

28

They showed no animus against the more conservative American revolutionaries, who were regarded as Anglo-Saxons too (even one who was half Huguenot), but they were strongly hostile to America’s Revolutionary myths. Paul Revere continued to be celebrated by these authors, but more for his character than his cause. One called him a “man of solid substance,” who was “quite unconscious of the heroic figure which he was to make in history.” At the same time Longfellow’s legend of the midnight ride was derided, and the patriot myths were furiously attacked. Behind this work lay a dream of Anglo-Saxon solidarity that was as romantic in its own way as Longfellow’s myth of the lone rider.

29

The American Anglophiles produced a large crop of monographs on the battles of Lexington and Concord. Among them was Frank Coburn’s study,

The Battle of April 19, 1775,

privately published in 1912. Coburn reconstructed the details of the battle with great care, and traced on his bicycle the routes of the midnight riders and the marching armies, calculating distances on his bicycle speedometer, calibrated in eighty-eighths of a statute mile. The result was an interpretation that mediated not only between Britain and the United States, but also between Lexington and Concord, and even between the partisans of Paul Revere and William Dawes. Coburn summarized his theme in a sentence: “I am glad to add,” he wrote, “that the bitterness and hatred, so much in evidence on that long ago battle day, no longer exist between children of the great British nation.”

30

Anglophile interpretations acquired a new urgency during the First World War. In 1917, an American film about Paul Revere’s ride was ordered to be seized under the Espionage Act, on the ground that it promoted discord between the United States and Britain. The case was heard in the Federal District Court of Southern California, and called

United States

v. The Spirit of Seventy Six.

31

An Age of Disbelief: The Myths of the American Debunkers

An Age of Disbelief: The Myths of the American Debunkers

At the same time, another line of interpretation was also developing—a school of historical skepticism that was hostile to the myth of the midnight ride for different reasons. Early expressions of this attitude appeared in an unexpected place—the writings of the Adams family. They had a score to settle with Paul Revere. In the early republic Revere had become a high Federalist, in company with many merchants and manufacturers in New England who had little liking for the presidency of John Adams, and even less for what Boston regarded as the “apostasy” of John Quincy Adams. That hostility was reciprocated by the Adams family toward Boston in general, State Street in particular, and Paul Revere

among the rest. The Adamses expressed strong resentment against what they regarded as the absurd inflation of Paul Revere’s reputation. In 1909, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., expressed his outrage “in the matter of Mr. Longfellow, and the strange perversion he has given to historical facts as respects Paul Revere and his famous ride.” Adams wrote that the duty of the historian was to “exorcise, so to speak, a popularly accepted legend.” Adams’s strongest resentment was against Longfellow, but there was no love lost for Paul Revere.

32

Others were happy to take up this task of historical “exorcism.” As early as 1896, Helen More contributed a sarcastic scrap of light verse called “What’s in a Name?” which suggested that William Dawes did the work and Paul Revere got the credit.

Tis all very well for the children to hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere;

But why should my name be quite forgot

Who rode as boldly and well, God wot?

Why, should I ask? The reason is clear—

My name was Dawes and his Revere.

33

The prominence of William Dawes increased when his descendant Charles Dawes became Vice President of the United States under Calvin Coolidge. Several accounts asserted (with as much inaccuracy as Stiles and Longfellow) that Dawes had succeeded in reaching Concord when Paul Revere was arrested. There was no truth in this idea, but it was widely repeated.

In the popular press, Paul Revere became increasingly an object of good-humored derision. The

Boston Globe

on April 19, 1914, marked the anniversary of the midnight ride by publishing an irreverent satire called “The Ride of the Ghost of Paul Revere, by Two Long Fellows.”

It was two by the village clock

When his inner tube gave a hiss.

He felt the car come down with a shock,

He jacked, and pried, and pumped, and said,

“I wish I’d come on a horse instead.”

This mood grew stronger in the era that followed the First World War, when patriotic symbols everywhere came to be regarded with increasing suspicion. The word “debunk” was first recorded in 1923 to describe this new school of historical criticism. The legend of Paul Revere’s ride instantly became a favorite target. There was little anger or hostility in this literature, but much good-natured contempt, and sophomoric humor that rings strangely in the ear of another generation.

34

Even Paul Revere’s horse was debunked. Patriotic engravers in the 19th century had represented Brown Beauty as a fine-boned thoroughbred. Debunkers in the 20th century took pleasure in proclaiming that Paul Revere was actually mounted on a plodding plough horse. That revision was as mistaken as the image it was meant to correct, but it came to be widely repeated in the 1920s, and has crept into the historical literature.

In 1923, one exceptionally bold debunker went so far as to assert that the midnight ride never happened at all. At that point, the President of the United States felt compelled to intervene. “Only a few days ago,” Warren Harding declared with high indignation, “an iconoclastic American said there never was a ride by Paul Revere.” The President was shaky in his facts, but rock-solid in support of Paul Revere. “Somebody made the ride,” he reasoned, “and stirred the minutemen in the colonies to fight the battle of Lexington, which was the beginning of independence in the new Republic in America. I love the story of Paul Revere, whether he rode or not.”

35

Through the 1920s, debunkers were strongly resisted by filiopietists who defended the patriot myths with high enthusiasm, sometimes in surprising ways. In 1922, Captain E. B. Lyon of the U.S. Army followed the path of Paul Revere’s midnight ride in a military aircraft, dropping “patriotic pamphlets” along the way.

36