Pastoral (6 page)

Authors: Andre Alexis

Gift, let me put it by and begin again.

Make me anew in the fire of your true love.

Make me in the balm of your mercy. Teach me

The divine art, forgiveness, that brings peace,

And in peace let me know love again, new forged

From the broken remnants of my ruined Self.

Amen.

This prayer was not what she needed. The time would come for forgiveness and

rebuilding, but not yet. Not until she had settled matters for herself.

rebuilding, but not yet. Not until she had settled matters for herself.

During his first months in town (with Lowther's guidance and, most often, his company), Father Pennant took to exploring the

fields and woods around Barrow: open fields, abandoned farms, fields lying

fallow. All of this walking and looking was done to familiarize himself with

the new world: shrews, deer mice, milkweed, monarch butterflies, deer flies,

horseflies, blackflies, dragonflies. He noted what he saw, where and when

things were seen, and he drew (precisely and beautifully) the flora and fauna

of the place. His forays brought him considerable pleasure, as well as

instilling the sense that he was getting to know the land at the same time as

he got to know the people who lived on it.

fields and woods around Barrow: open fields, abandoned farms, fields lying

fallow. All of this walking and looking was done to familiarize himself with

the new world: shrews, deer mice, milkweed, monarch butterflies, deer flies,

horseflies, blackflies, dragonflies. He noted what he saw, where and when

things were seen, and he drew (precisely and beautifully) the flora and fauna

of the place. His forays brought him considerable pleasure, as well as

instilling the sense that he was getting to know the land at the same time as

he got to know the people who lived on it.

In all of this, Lowther was a wonderful companion. He was a naturalist of

sorts, infallible when it came to birds and trees. He could, for instance, tell

most birds by their song, and it was a pleasure to walk with him, if only

because it greatly increased Father Pennant's awareness of the sounds this bright world made. Moreover, April and May

provided them with ideal weather: sunshine, light rain from time to time, cool

nights, more sunshine. The plants were nourished and thriving and it was

exquisite to go out on dew-wet mornings to explore the greening: weeds,

flowers, cow manure, sheep shit, the wet spoor of deer, coyotes and, in one

field, what looked to be the spoor of a bear, fresh.

sorts, infallible when it came to birds and trees. He could, for instance, tell

most birds by their song, and it was a pleasure to walk with him, if only

because it greatly increased Father Pennant's awareness of the sounds this bright world made. Moreover, April and May

provided them with ideal weather: sunshine, light rain from time to time, cool

nights, more sunshine. The plants were nourished and thriving and it was

exquisite to go out on dew-wet mornings to explore the greening: weeds,

flowers, cow manure, sheep shit, the wet spoor of deer, coyotes and, in one

field, what looked to be the spoor of a bear, fresh.

One day, when Lowther was unexpectedly called away and could not go with him to

the old Stephens place, he warmly insisted Father Pennant explore the abandoned

farm on his own. The farmhouse looked to be sturdy, though it smelled of wood

that had rotted. The barn was ready to collapse on itself, as if a great hand

had pressed down on it and burst its roof. Decades previously, the Stephenses

had planted apple trees in a modest, ordered grove: thirty trees in tight rows,

five by six. At a distance from the apple trees there were other trees

(willows, birches and maples), tall, yellowed grasses, thistles, buttercups and

an unexpected clump of purple lilac bushes that intoxicated with their perfume.

A brook, a tributary of the Thames, ran across the property: narrow, four feet

across, its waters clear as glass, its banks low and rounded to an overhang in

places. In and around the brook: turtles, frogs and small fish that swam like

living slivers of birch bark. Beyond the brook, a wide, open field, alive with

grasshoppers, crickets and mice.

the old Stephens place, he warmly insisted Father Pennant explore the abandoned

farm on his own. The farmhouse looked to be sturdy, though it smelled of wood

that had rotted. The barn was ready to collapse on itself, as if a great hand

had pressed down on it and burst its roof. Decades previously, the Stephenses

had planted apple trees in a modest, ordered grove: thirty trees in tight rows,

five by six. At a distance from the apple trees there were other trees

(willows, birches and maples), tall, yellowed grasses, thistles, buttercups and

an unexpected clump of purple lilac bushes that intoxicated with their perfume.

A brook, a tributary of the Thames, ran across the property: narrow, four feet

across, its waters clear as glass, its banks low and rounded to an overhang in

places. In and around the brook: turtles, frogs and small fish that swam like

living slivers of birch bark. Beyond the brook, a wide, open field, alive with

grasshoppers, crickets and mice.

As it had done when he was beside the Queen, the water held Father Pennant's attention for a time. It ran pure and quick, looking like a strand of clear

muscle. And it seemed to Father Pennant as if he could have lifted the brook

out of its channel, as he would ligaments and fascia from an animal he had

dissected. What was it about the streams in this part of the world?

muscle. And it seemed to Father Pennant as if he could have lifted the brook

out of its channel, as he would ligaments and fascia from an animal he had

dissected. What was it about the streams in this part of the world?

Father Pennant stepped across the brook at its narrowest point and began to

explore the rest of the field. The land was so alive, it felt as if he could

have put a hand down into the tall weeds, without looking, and picked up a

living creature. And he was thinking how much he would have liked to hold a

deer mouse or a shrew in the palm of his hand when he heard a

click

like the sound of a twig snapping and a cloud of gypsy moths rose from the

grasses.

explore the rest of the field. The land was so alive, it felt as if he could

have put a hand down into the tall weeds, without looking, and picked up a

living creature. And he was thinking how much he would have liked to hold a

deer mouse or a shrew in the palm of his hand when he heard a

click

like the sound of a twig snapping and a cloud of gypsy moths rose from the

grasses.

That in itself was strange. Gypsy moths usually ate tree leaves. They were the

last thing one would have expected to find in the tall grass. But stranger

still, the moths flew up as one and formed, with their wings and bodies, two

distinct shapes. First the moths aligned themselves in such a way as to create,

from Father Pennant's perspective, an elongated loop:

last thing one would have expected to find in the tall grass. But stranger

still, the moths flew up as one and formed, with their wings and bodies, two

distinct shapes. First the moths aligned themselves in such a way as to create,

from Father Pennant's perspective, an elongated loop:

There could be no mistaking this for a random configuration. Then, as if to

confirm that very thought â that they had purposely created a loop â the gypsy moths dispersed then regrouped to form a flawless circle:

confirm that very thought â that they had purposely created a loop â the gypsy moths dispersed then regrouped to form a flawless circle:

They fluttered in formation for some time before falling to the ground.

Father Pennant had never seen nor ever heard of anything like this. He was at

first puzzled, unable to quite believe what had happened. He had been surprised

by the first pattern the moths made (the loop), but he was, as time passed,

frightened by the circle they had formed. He could not help feeling that such a

perfect circle had some special meaning, a meaning meant for him alone, but he

couldn't for the life of him imagine what it might be. It was as if some being had

spoken to him in an extraordinary language and expected him to understand. But,

if so,

who

had sent the insects to âspeak' with him?

first puzzled, unable to quite believe what had happened. He had been surprised

by the first pattern the moths made (the loop), but he was, as time passed,

frightened by the circle they had formed. He could not help feeling that such a

perfect circle had some special meaning, a meaning meant for him alone, but he

couldn't for the life of him imagine what it might be. It was as if some being had

spoken to him in an extraordinary language and expected him to understand. But,

if so,

who

had sent the insects to âspeak' with him?

No, there had to be something wrong with the moths. He looked about the field,

but though there had been quite a number of them, Father Pennant could find

none on the ground. Here was another puzzling thing: it wasn't possible for so many moths to vanish so quickly. Thinking that deer mice must

have eaten them all, he gave up his search for moths after half an hour,

disappointed. He drew what he had seen:

Lymantria dispar

, brownish-grey with a brown fringe at the bottom edge of its wings when the

wings were closed, its antennae like two delicate, minuscule feathers, its body

a narrow, umber cylinder with six thin white stripes that transversed it at

almost regular intervals. Perfectly common. They had been gypsy moths, no doubt

about it, despite the strangeness of their behaviour.

but though there had been quite a number of them, Father Pennant could find

none on the ground. Here was another puzzling thing: it wasn't possible for so many moths to vanish so quickly. Thinking that deer mice must

have eaten them all, he gave up his search for moths after half an hour,

disappointed. He drew what he had seen:

Lymantria dispar

, brownish-grey with a brown fringe at the bottom edge of its wings when the

wings were closed, its antennae like two delicate, minuscule feathers, its body

a narrow, umber cylinder with six thin white stripes that transversed it at

almost regular intervals. Perfectly common. They had been gypsy moths, no doubt

about it, despite the strangeness of their behaviour.

Or had he been dreaming? He waved his right hand before his eyes. And saw it.

He cleared his throat and heard the sound. Aside from the fact that he had just

witnessed something unaccountable, he was â or felt he was â as normal as could be: a Catholic priest in Barrow at a time of year â mid-spring â when gypsy moths are about.

He cleared his throat and heard the sound. Aside from the fact that he had just

witnessed something unaccountable, he was â or felt he was â as normal as could be: a Catholic priest in Barrow at a time of year â mid-spring â when gypsy moths are about.

As he always did when he was bewildered or thought about God's grandeur and mystery, he kneeled down to pray. He kneeled in the weeds, among

the insects and rodents, and prayed for enlightenment. What were his duties,

now that he had been given a vision?

the insects and rodents, and prayed for enlightenment. What were his duties,

now that he had been given a vision?

There was great comfort in prayer. It was not so much that he felt the presence

of God when he prayed, though he did at times feel His presence and that always

brought him peace. It was that kneeling â head bowed, fingers interwoven and held on his chest â immediately brought to his mind all the times he had surrendered to the mystery

that was the world and to the mystery that was God. Comfort came from the

continuity of submission. Kneeling, praying, he was himself at his most open

and at his most genuinely human: ignorant, hopeful, humble in the face of the

unknown.

of God when he prayed, though he did at times feel His presence and that always

brought him peace. It was that kneeling â head bowed, fingers interwoven and held on his chest â immediately brought to his mind all the times he had surrendered to the mystery

that was the world and to the mystery that was God. Comfort came from the

continuity of submission. Kneeling, praying, he was himself at his most open

and at his most genuinely human: ignorant, hopeful, humble in the face of the

unknown.

The man who had gone to the old Stephens field was, for a time, different from

the man who left it. The new Father Pennant was rattled and uncertain. On

entering the field, he'd believed he was getting to know the county and its people. Barrow and the land

around it had struck him as marvellously new, but not mysterious in any

metaphysical sense. The certainty that Barrow and Lambton County were ânormal' was taken from him when he saw moths flying in a circle, a fluttering hoop

suspended in mid-air. But this uncertainty wasn't certain either. As the days passed, he grew less sure that he had seen the

moths in wilful pattern. The whole episode began to seem incredible and he was

relieved he'd chosen to keep details of the day to himself. Lowther would almost certainly

have thought him unstable.

the man who left it. The new Father Pennant was rattled and uncertain. On

entering the field, he'd believed he was getting to know the county and its people. Barrow and the land

around it had struck him as marvellously new, but not mysterious in any

metaphysical sense. The certainty that Barrow and Lambton County were ânormal' was taken from him when he saw moths flying in a circle, a fluttering hoop

suspended in mid-air. But this uncertainty wasn't certain either. As the days passed, he grew less sure that he had seen the

moths in wilful pattern. The whole episode began to seem incredible and he was

relieved he'd chosen to keep details of the day to himself. Lowther would almost certainly

have thought him unstable.

He might even have forgotten about the moths, but then, while collecting the

mail one day not long after his episode in the Stephenses' field, he found a postcard for Lowther. It was from Cartmel Priory, in England.

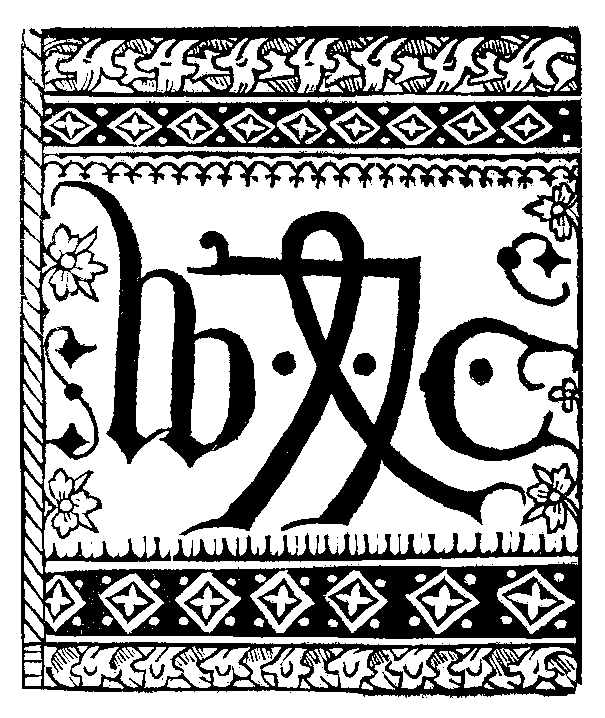

On the front was the picture of an old church. But on the back, where a

signature might have been, was a mark: a one inch by one inch square, with an

element that reminded him of the loop the moths had made:

mail one day not long after his episode in the Stephenses' field, he found a postcard for Lowther. It was from Cartmel Priory, in England.

On the front was the picture of an old church. But on the back, where a

signature might have been, was a mark: a one inch by one inch square, with an

element that reminded him of the loop the moths had made:

Father Pennant kept the postcard until evening when he and Lowther were at the

dining room table. Lowther had, as usual, prepared a lovely meal â white fish, olive bread, lemons, capers, a vinaigrette, a tossed salad. He

seemed slightly distracted, or perhaps more thoughtful, but it did not detract

from his duties. (The rectory would smell of the olive bread he'd made, for days.)

dining room table. Lowther had, as usual, prepared a lovely meal â white fish, olive bread, lemons, capers, a vinaigrette, a tossed salad. He

seemed slightly distracted, or perhaps more thoughtful, but it did not detract

from his duties. (The rectory would smell of the olive bread he'd made, for days.)

â Lowther, said Father Pennant, a postcard came for you today. I hope you don't mind, but I was struck by this lovely woodcut on the back, so I hung on to it

for a bit. Do you know where the woodcut comes from?

for a bit. Do you know where the woodcut comes from?

Lowther took the postcard.

â Yes, he answered. This is from Heath, the man who was with me when we first

met. He was adopted, but a long time ago he found out his real family's descended from William Caxton, the owner of the first printing press in

England. That woodcut is Caxton's symbol.

met. He was adopted, but a long time ago he found out his real family's descended from William Caxton, the owner of the first printing press in

England. That woodcut is Caxton's symbol.

â Oh. It looked like a rune.

â Nothing that exotic. Just a signature. You know, Heath and I have known each

other since grade school. And he's been using that woodcut for a long time. I don't even notice how it looks anymore. It is beautiful, though, isn't it?

other since grade school. And he's been using that woodcut for a long time. I don't even notice how it looks anymore. It is beautiful, though, isn't it?

â What does he do for a living?

â That's hard to say. He used to be a farmer. Then he worked for Massey Ferguson. Then

he made a lot of money selling a fertilizer he invented. He still farms a

little, but now, I think, he mostly invents things.

he made a lot of money selling a fertilizer he invented. He still farms a

little, but now, I think, he mostly invents things.

â I'd like to meet him again, said Father Pennant. We never got a chance to talk.

So it was that, three weeks after the incident with the moths and a week after

Heath Lambert had returned from the Lake District â where he'd been travelling â Father Pennant was in a house at the outskirts of Oil Springs waiting for

Lambert to come in from a back garden where he was gathering rhubarb leaves to

use in an insecticide.

Heath Lambert had returned from the Lake District â where he'd been travelling â Father Pennant was in a house at the outskirts of Oil Springs waiting for

Lambert to come in from a back garden where he was gathering rhubarb leaves to

use in an insecticide.

Other books

Musical Beds by Justine Elyot

Constable Evans 02: Evan Help Us by Rhys Bowen

The Girls by Helen Yglesias

And Then One Day: A Memoir by Shah, Naseeruddin

Healing the Wounds by M.Q. Barber

The Game of Seduction (Arrington Family Series) by Candace Shaw

They Walk by Amy Lunderman

The Ring Bearer by Felicia Jedlicka

Allegiance Sworn by Griffin, Kylie

No Limits by Alison Kent