Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (45 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

As soon as I return to America, I arrange to fly out to Ann Arbor to meet Ernest Fontheim—he seems excited to meet me, tells me to stay at Weber’s Inn for its indoor pool and fine hospitality. We debate dates, and shyly discuss the wonder of discovering each other. He cannot see me the night I arrive, then he suggests I stay only one night; our interview will last less than a day. Despite those restrictions, I am thrilled. In the back of my mind, I have Jean-Marc’s warning about not relying on ninety-year-olds, or, at least, not expecting much from ninety-year-olds, but I am too excited to know someone who knew Hans and Valy, intimately; someone who can provide answers—even to the simplest things, like where and how they lived. How they fell in love! What their love was like—and what they experienced each day, how they experienced each day, from the most minute, to the broadest expression of their time.

“As you know,”

Ernest wrote Ilse Mayer,

“[Hans] was alone in Berlin [i.e., without his parents] and shared a furnished room with another young Jewish man of roughly the same age, Karl-Hermann Salomon, in a fifth-floor walk-up apartment in the

Hinterhaus

of Brandenburgische Strasse 43, Berlin-Wilmersdorf.”

This meant the “backhouse”—these old Berlin buildings had a “front” and a “back,” with a courtyard in between, or even two courtyards and more buildings, all connected to the same address. When I first visited, I hadn’t known which part of the building they lived in. I had just wandered through, looking up, looking around.

They sublet the room from a Jewish widow, a certain Mrs. Striem. I vaguely remember that Hans told me that before being drafted to work for Siemens he went to the Chemieschule. That was a school run by the Jewish community of Berlin where students could learn the elementary aspects of chemistry to enhance their employment opportunities abroad in case they could still emigrate. For many of the students, the Chemieschule also served as a substitute university. Hans and Karl-Hermann were not close personally, and in fact Hans felt that KH often rubbed him the wrong way. I myself lived at home, a few blocks away at Eisenzahnstrasse 64 where my family (my parents, my younger sister, and I) sublet two rooms in a larger apartment belonging to an aunt and uncle of my mother. In addition to my family and my mother’s aunt and uncle, the latter’s son and two unrelated widows [all together nine people] lived in the apartment which originally only served my mother’s aunt and uncle. In those days all Jews in Berlin were squeezed together in so-called Jew-houses. That was one of the great ideas of the Generalbauinspektor für die Reichshaupstadt, Albert Speer. I had somewhat strained relations with my parents and Hans was all alone in Berlin. So we became each other’s confidants and did many things together in our limited free time.

At first I think, when Ernest arrives in the crisp, freezing morning to get me, crunching across the snow in practical boots and a massive jacket, Jean-Marc is wrong. Ernest is brilliant. He is rounding past ninety, and he is stooped, held up as much by his suspenders as his ever-sagging spine, his face craggy, his voice, within an hour of talking, loses energy, tone, and level. He still drives, a faux-fur-lined hunter’s cap pulled down tightly over his ears, and he banters without pause as we head from the inn into a cluster of professors’ homes in the Michigan suburbs. He is shyly pleased I have made so much effort to meet him, makes a huge fuss over the cookies I brought to give him and his wife. But then I am disappointed beyond reason: he is happy

to welcome me into his home, but also adamantly determined that he will write his own memoirs. He is guarded with me and my three recording devices, my videos; he is afraid that I will publish his story before he can. That I will take it from him; render it mine and not his. He will not, he says patiently, but intractably, reveal anything further than what I have already read in my letter—or rather, his letter to Ilse, that Carol gave me in London. He will not give me anything further, nothing beyond the story of Hans, he will offer nothing about his own miraculous saving. He has given a testimony to the Holocaust Museum, he says, and as he sees me write that down, he adds that the contents of that interview are sealed until the event of his death or the publication of his memoirs. At the end of our first two and a half hours of speaking, he says, essentially,

anything that is not about Hans is off-limits to you

.

I don’t want my life in print before I write it myself

. I reassure him I won’t take his story. I understand his determination; in fact, I admire it. It is, in a way, a version of what the former Kindergartenseminar student Inge Deutschkron said to me in Berlin—we American Jews, so anxious to scoop up these stories, to take them for ourselves, we help ourselves to them, as though they are our birthright. We try to take more than our fair share, really. And here is Ernest Fontheim, who lost his whole family—who am I to take

his story, too? Who am I to steal the narrative, the one thing he retained?

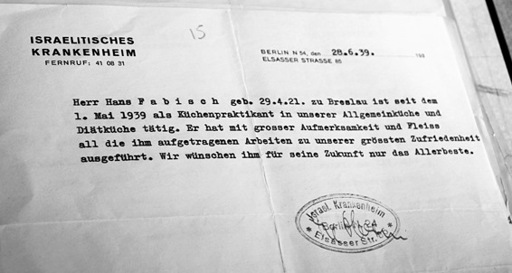

The Jewish Hospital’s notes on Hans, 1939. “We wish him only the best for his future.”

And yet I am also, selfishly, terribly frustrated. I offer to write a separate book—a separate something—

I could be your interlocutor,

I say, thinking this might be a solution.

I can write your story—you can dictate it.

He smiles and says, “That’s generous,” but he declines.

But, as Ernest said on the phone, he is willing to talk a bit about Hans. The two men met on the first day they were conscripted for forced labor at the

Elektromotorwerk

—the electronic motor division—of Siemens on April 29, 1941, Hans’s twentieth birthday. Explains Ernest, “He was almost exactly a year and a half older than I. We hit it off from the very first day. We had similar backgrounds, similar education, a similar sense of humor, and looked at life and our situation in much the same way. In many ways he was an inspiration for me.” Both had been pulled from school far too young. The two young men were from an intellectual tradition, and now they were dying intellectually, banned from all cultural events and academic pursuits. It was daily agony; so together they gathered a group of young Jews, all forced laborers, all with connections to Jews banned from their professions. They set up an underground salon, in essence: after the factory shift, the older Jews gave lectures to the younger ones: an architect; a former epidemiologist, who had run the city of Berlin’s epidemic response team from the city hall before 1933. For a moment, the disorienting, impoverishing, impact of all these accomplished Jews suddenly finding themselves without a perch, without their status, without their jobs, their livelihoods, was temporarily suspended. It was a respite from the desperation, and exhaustion. Someone had managed to scrounge an old phonograph, and others had saved recordings from symphonies. They played them, very, very quietly so as not to alert their neighbors, and they closed their eyes, pretending they were back in the concert halls of their youth.

Ernest and Hans began work each morning at six a.m., a shift that lasted until four p.m., with two thirty-minute breaks. To make the six

a.m. clock-in, which meant a 5:45 arrival at the factory gates, Hans and Ernest would take the first S-Bahn train of the morning, which left their area of Berlin at 5:15. The streets would be as black as the inside of a closet, an unnatural urban inky hue, with streetlights darkened and apartment buildings shuttered, all prevented from emitting light so as not to attract bombers. Ernest and Hans would meet at the corner of Kurfürstendamm at a precise moment and whistle to each other. They were exhausted, constantly, and the companionship was as much motivational as it was practical. At Siemens, they were hustled into packs of Jewish workers, separated from their Aryan counterparts. Jews were not allowed to be sprinkled among the other workers, lest they perform sabotage, undermine the effort. All movement was strictly patroled. Jewish workers ate lunch standing, at their workspace—Aryans could use a cafeteria—and bathroom breaks for Jews were at nine a.m. and one p.m., in a group, led by a foreman. Visiting the toilet alone was not an option.

Hans and Ernest riveted commutators, the rotary electrical switches for motors. It was long and boring work, always on their feet. Ernest remembers forty or fifty Jewish forced laborers, men and women, old and young; the youngest were two fourteen-year-old boys. None of these laborers had ever worked in a factory before. All were hoping for a swift Allied victory. I expressed surprise he knew so many young people left in the city. But of course, he said, there were kids who were too old for the Kindertransport, or whose families had not been able to get their children on a transport (there was a strict, limited number of spaces) or had simply not opted for it, as they couldn’t imagine separating themselves from their children; there were those whose entire families had tried to emigrate, but were unsuccessful, especially those who tried to leave after Kristallnacht, when the consulates were mobbed and the chances were dim. Among them was

Margot, the woman who would, after the war, become Ernest’s wife, and before that, the woman with whom he would go into hiding. But

though he filled me in on some of the details, under Ernest’s strict instructions, that story can’t be told here.

As harsh as the working conditions were, the hunger was nearly as bad. From the beginning of the war, on the first of September 1939, Germany introduced rationing for all food, says Ernest, stirring a cup of tea. “Dairy. Wheat. Vegetables. Fruits were subject to rationing, and ration coupons were passed out, including to Jews. There were three levels of ration coupons. One was a general consumer—

Normalverbraucher

. Then a higher category, somewhat bigger rations for workers—

Arbeiter

—and then the highest category was heavy workers, people like miners—

Schwerarbeiter

. The work we did at Siemens would have qualified us for workers’ cards, one level up from general consumer. But we didn’t get that. We got ‘normal consumer,’ and then after some time, cards were cut below that of the general consumer. The meat and meat product ration card was totally eliminated so you couldn’t buy any meat anymore, and meat also included poultry, of course. And meat products like sausages and so on. Oh, and also in addition to food, also tobacco was rationed.”

So were clothing cards. They both wore the same clothes they had worn for the last two years. They could not replace them. But Ernest insists they felt only anger and indignation, not fear. They wanted to thwart the system, to thumb their noses at their overseers; they did not think of danger, they thought of escape.

To Carol’s mother, Ernest wrote:

Starting on September 19, 1941, every Jew had to wear a yellow Star of David when appearing in public. That measure not only made us Jews targets of all kinds of harassment, but also enabled the government to issue a list of additional restrictions on our freedoms, which now became easy to enforce. Jews were permitted shopping only one hour per day, from 4 to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, and no shopping at all on Saturday. Under wartime conditions, practically all shopping consisted of food buying. In the era before supermarkets, one had to go to the butcher, the baker, the dairy, and the greengrocer, and in each of these stores there was always a line. If a Jew had stood in line for, say, fifteen minutes, and it was 5 o’clock, he had to leave the store without having bought anything. Any German had the right to get in line in front of a Jew. Even if a merchant would have wanted to serve the Jew after 5 o’clock, he did not dare for fear that one of the other customers might denounce him. Most working Jews returned from their jobs only after 4, some not until shortly before 5 (like Hans and I for example). For these people buying the meager rations became in itself a nightmare.

Both Hans and Ernest were forced to matriculate at Jewish schools after 1938 and that communal experience—combined with some natural teenage rebellion—meant they both felt much more Jewish than their extremely secular, extremely assimilated parents. By the fall of 1941, they were almost defiantly eager to put on the star. That said, everything got harder once the star came on. The curfew imposed on Jews—eight p.m. in winter, nine p.m. in summer—was rigorously enforced by Gestapo spot checks, and it did not mean simply to be inside—it meant to be ensconced in the home at which you were registered. “A classmate of mine came home ten or fifteen minutes after curfew,” says Ernest, explaining how they knew not to test these hours. Gestapo officers were at this tardy friend’s house when he arrived home. “They took him right away. For a half a year he was in what they euphemistically called a ‘work-education’ camp, like a concentration camp. The inmates were brutally treated, they did hard work, with little food.” Ernest’s friend was “a big sportsman, he had a tall muscular figure, and [when] he came out from that year, he was a terrible sight. He was emaciated and looked practically different from how he looked before. So we knew, with that curfew, we had to religiously observe the restriction in order not to have such a fate.” When Hans and his friends met for their intellectual retreats—or just to be,

vaguely, social—it would be for an hour, or two; always they would arrange to break up their meetings in time for all to get home.