Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (15 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

In fact, he continues, there were a hundred sixty-five full

Juden

who survived at the hospital, eight hundred in all who survived in Berlin. Later I will read books on the hospital, and try to talk to those who worked there. Valy worked in the children’s ward of the hospital, when there were still children in Berlin. But, slowly, the Jewish kids in the city emigrate or are sent away.

“The children’s group was discontinued, and I became superfluous and left,”

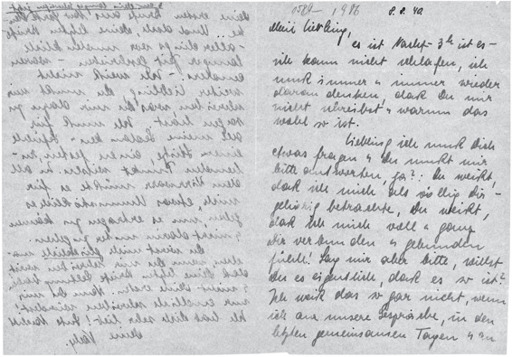

Valy writes in April 1940.

“Three afternoons a week I now teach health and nutrition issues. . . . In this manner I am able to make some money without taking on work in the afternoons. During the mornings I go to the hospital where I do not learn a whole lot, but still something. I lead my life the way I’ve been doing for the past 2 years: In a spirit of waiting, without much joy or hope. But, my darling, don’t feel sad for me; I want you to know that I have people around me—women,—you know that only women are left here?!”

Among the survivors, I will find no one who remembers the name Valerie Scheftel.

Like a handful of other academics, Pomerance had already been to the archives in Bad Arolsen once, but on a very tightly controlled tour with no opportunity to explore on his own. “Up until now, it has served the purpose of what its title is—the International Tracing Service—in other words, finding out fates,” Pomerance says. After the war, he continues, “descendants were left without really knowing exactly how or where their relatives died. People need a sense of finality, and that’s what the ITS has been offering people—family members—for decades.”

Pomerance mentions that he was shown a book in Arolsen that I might see there, too; it documents the number of lice on the heads of individual prisoners. “When you see those documents,” he says, “you think, ‘My goodness, there are people counting the number of lice on inmates’ heads.’ It’s part of the whole, greater picture. It kind of adds to the incomprehensibility of it all.” Even such a small mention in this type of file was enough to secure for a former prisoner the postwar indemnity payments. Or it might simply be the only evidence that a person lived at all.

“It is incredible what still can, all of a sudden, be discovered,” he remarks, musing on the discovery, in 2000, by the Jewish community of Vienna of a trove of files documenting the wartime history of the community that had languished, unattended to, in an attic for more than sixty years: all that yearning, all those efforts to escape, documented on curling paper, stuffed into filing cabinets, forgotten. Part

of that wealth of information was uploaded to the Web, waiting for those with names to search for. I tell him that at the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance, I found the Gestapo mug shots for my grandfather’s older half brother and his wife—Manele and Chaja Wildmann. It will be years before I realize that the trove of files we spoke of that day included a number that directly affected my family—that gave both reassurance and finality to Manele’s story.

But I don’t have that information yet.

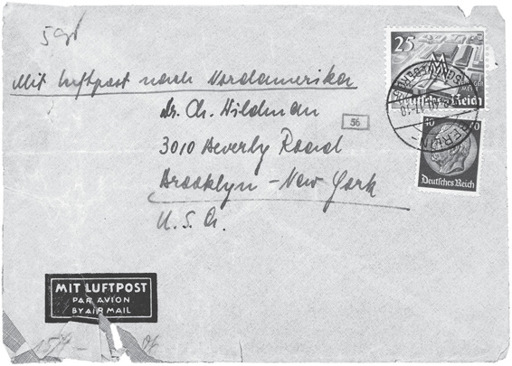

Instead, what we speak of is this: Nearly seventy years on, many believe that there are few “new” Holocaust discoveries to be found at Arolsen. Revelations, if they can be called that, are more likely to be of the kind I found in my parents’ basement, in the words of the victims preserved for seven decades, the pleas for help. There is great interest in the large body of letters, relatively intact, written by Jews trapped in Europe to those outside. They give texture to the destruction, depth to the history, a personal understanding of something so massive, so incomprehensible, it can otherwise seem too fantastic to absorb.

The night before I interview Pomerance, I meet with Dr. Andrea Löw from the Institute of Contemporary History at a trendy little waffle shop filled with purposely mismatched flea market furniture and attractive, hip twenty- and thirtysomethings in the Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood of former East Berlin. She is thirty-four, and she is the first person I tell on this journey that I am pregnant. I blurt it out, perhaps because we are surrounded, crushed in, by baby carriages; perhaps because she is only slightly older than I; and perhaps because, as always when I start on a Holocaust project, I feel very conscious of my own Jewishness. I tell her I am growing a little Jew. I am not sure she finds this amusing.

For Andrea’s work, Valy’s letters are just as important as any lists or new information she might come across at ITS. She thinks she

might be able to include a few in a multivolume collection of wartime documents she is helping to compile—her hope is to use the voices of the persecuted to humanize the stiff bureaucratic decrees that bloodlessly lay out, day after day, the orders to discriminate against and separate Jews from German society. Andrea reads a few of my photocopied letters as we eat our waffles. They are fairly typical of this type of correspondence, she says, looking for visas, affidavits, for exit doors. We see Valy’s fear rise from June 1940 when she writes,

“Darling, I have inquired repeatedly when my number will come up. All I get in response is some vague indication of one to two years.”

To the desperation of October 1941:

“Even if there were a possibility to do the expensive detour via Cuba, it would be too late because, meanwhile, German citizens between the ages of 18 and 45 are no longer allowed to emigrate. I cannot tell you how desperately unhappy I am about this!!!! What did you try to do, my darling? Oh, but I am afraid that it all will be to no avail. And I need you so badly! I need to be with you so much. My beloved, you can do so much, why can’t you take me to you? But I know that it will not be possible.”

But Andrea also prods me to consider how my grandfather handled the demands of dozens of cousins and friends, desperate and angry that he got out and they didn’t. It is the first time I discuss this idea of his guilt with someone else. She is sure it would have been awful, and she is also quite certain he was not alone in shouldering this burden, that everyone like him, every single refugee who made it to calmer shores, was engulfed by the burden of having left others behind. We both agree that the weight would have been too much to bear, it was so heavy, it couldn’t be processed daily, it had to be let go of—perhaps that spoke to his idea of

herrlich

, the marvelous, the need to make the world brighter in the midst of all that was so very dark.

We talk about the moral ambiguities of the period: What did my grandfather owe these cousins and friends? Why didn’t he take Valy with him? She herself never says that he left her, exactly, nor that he purposely didn’t take her; I suspect she would not have left her

mother

behind, in Czechoslovakia. And once she decided to come and join him, he was in no position to help—I tell Andrea about the receipts I found in the box of letters, which showed my grandfather was in the process of paying down loans from the National Committee for Resettlement of Foreign Physicians, in amounts so low he couldn’t possibly have had any extra cash to send abroad. He was quite poor in Vienna to begin with—and, like many refugees, he arrived with barely enough to start his own life. In turn, she tells me the story of refugees who tried, unsuccessfully, for years, to get parents out of Germany. They never forgave themselves, she says, though they exhausted every means they had at their disposal. It is a reminder that these stories, so often, have no happy ending, are unhappy at their core.

Our waffles finished, we stand to leave. It seems somehow incongruous, our conversation, set against the brilliance of a June day in Berlin, the city in full bloom, so warm and inviting and hip and cool. Everyone is on a bicycle, there are dozens of children running and playing in the streets of Prenzlauer Berg, and I walk to meet a German friend at an outdoor Vietnamese restaurant with massive paper lanterns that sway above our heads as we eat from terra-cotta bowls; we banter as though I haven’t spent the day immersed in the past. The juxtaposition is jarring. It couldn’t be more different from the postwar newsreel images, and not only because the streets, in many places of this incredible town, bear little resemblance to what was before. The city of Berlin was so incredibly damaged, and so much of what is here is new—though throughout the former East, there remain gaping holes where bombings took out whole buildings. It is a sharp contrast from Vienna, so perfectly preserved or reconstructed it is a museum.

I’m eager to get going. I want to ask people about who Valy might have been and what she might have experienced. But I also want to know what the popular—and academic—expectations are for the Bad Arolsen ITS archives. I want to know, so to speak, whether there is anything in that bag for me.

Before I get to Arolsen, I have two more stops to make. The first is to Wolfgang Benz, one of the preeminent scholars in the field of Holocaust studies and director of the Center for Research on Anti-Semitism, deep in former West Berlin. He was born in 1941, and when he is asked why he is a Holocaust historian, he parries with, “Why do you use a pencil?” He believes ITS is much ballyhoo about nothing—stirred up largely by misinformed Americans. “This was the campaign,” he says, running his hands through wildly unkempt white hair.

“The greatest archives of the Holocaust!”

He makes his voice deep and mean. “

And the Germans! They will not show us! Terrible!

It’s garbage.” He slumps back in his chair. The archives are just “lists,” he tells me. The only “scandal” of Arolsen, he says, is when the “eighty-two-year-old Ukrainian man” asks for compensation for being a forced laborer, and the archive staff is not fast enough with information to ensure he receives payment in his lifetime.

“For normal people, ninety-five percent of the material in Arolsen is extremely dull. It’s just working papers. No decisions. No secrets of the Nazi state . . . Maybe some journalists picture archives as a dark room and you come in and

here lies Hitler’s personal testimony

and here the archivist is like a magician and says, ‘Oh! You cannot read this!’” He makes a face. “It is an

archive

with material concerning German camps. Camps of all types.”

I switch subjects and ask him again about Valy. Are small stories important? His entire manner shifts. “Yes,” he says, immediately. “As historians we can describe what happened. Where it happened. But we cannot exactly describe

why

it happened. The historian cannot describe the suffering of the individuals. Therefore we

need

the memorials. We need the letters, the diaries, the memories of the individuals. As the main part of the picture of what happened.”