Pagan's Daughter (6 page)

Navarre mumbles something that could be an apology. I don’t even bother. It can’t get much worse for me, now: an apology won’t make any difference.

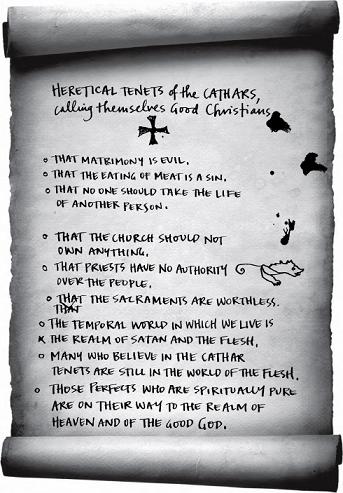

‘Babylonne,’ says Benedict, peering at me with his muddy green eyes, ‘would you rather live in darkness, among those damned for eternity, than follow the difficult path of righteousness?’

Beg pardon?

‘Because that’s what you’ll be doing, if you fail in your life here.’ He sighs again. ‘If you do not wish to become a Perfect, in pious communion with other women dedicated to the way of Christ, then you will have to get married. There is no other choice.’

What?

‘Oh, but—’

‘We can’t do that, Holy Father!’ Navarre jumps in. She sounds worried. ‘We can’t marry her off! Her mother would never have allowed it!’

And suddenly Gran interjects. ‘She might be a bastard,’ Gran creaks, ‘but she is Mabelia’s bastard. We can’t endanger her immortal soul.’

Benedict frowns. I don’t think he’s used to having women argue with him.

‘Then you must look to your own strength,’ he says irritably. ‘It seems to me that you must either suppress the demon in her, or condemn her to marriage.’

You can’t be serious. Condemn

me

to marriage? Who on earth would want to marry

me

?

‘My sister died a martyr,’ Navarre frets. ‘We owe it to her memory that her child be kept from sin. Babylonne might deserve perpetual torment, but her mother is in Heaven now. Should we keep her child from her, by condemning Babylonne to eternal damnation on earth?’

‘Babylonne can always repent on her deathbed,’ Benedict points out, as if I’m not even here. ‘The

consolamentum

will save her then.’

‘But suppose, when she dies, there are no Perfects around to give her the

consolamentum?

’ says Navarre. ‘If that were to happen, I would have failed her mother. We all would. And I swore that I would never fail Mabelia.’

‘You

swore?

’ Benedict draws himself up in his seat. ‘With an

oath?

’

‘Oh no!’ It’s wonderful to see Navarre looking so cowed. ‘I mean, I made a promise. To God. I didn’t take any oath.’

‘Babylonne!’ It’s Gran. She’s come to life again. ‘Out,’ she says, and jerks her chin at the back door.

What? You’re not serious.

‘Yes, Babylonne. Out you go. You shouldn’t be here.’ Navarre doesn’t want me to see her being scolded by a Good Man, any more than Gran does. ‘Go and chop the wood.’

‘But—’

‘Do it!

Now!

’ Navarre turns to Benedict. ‘You see, Father? She’s so disobedient.’

I should have known it. They’re going to marry me off without even waiting to hear what

I

might say on the subject. Not that my opinion counts for anything. But they could at least let me stay and listen.

Chop the wood. Hah! I don’t need to chop the wood; it’s in splinters already. But if they don’t hear the sound of chopping, they’ll probably throw

me

on the fire. For disobeying orders in front of Benedict de Termes.

Out into the little yard, where Navarre’s beans are failing. (Not enough sun for those beans, because the walls are too high.) Mud and dung and old straw and—yuk! Rats in the woodpile again. I honestly can’t understand why those rats stay around, since there’s never a scrap of food to eat. Perhaps they know about Perfects. Perhaps they know that Perfects can’t kill any living creature— not even a rat.

If you ask me, we should get ourselves a dog. A really good rat-killer. If our dog killed the rats, we couldn’t be blamed for it, could we? And we could name him after the King of France.

Louis, you mangy son of a toothless bitch

, we could say.

Come here and soak Gran’s bread for her!

Gran might profit from a mouthful of dog-piss once in a while.

Yes, it would be good to have a dog. Except that the poor creature would die of starvation, because we couldn’t feed him any meat. He would have to live on fish and barley, and that’s not much of a life for a dog.

Probably better than

my

life, mind you. I don’t know. Maybe I should get married. Except that—well, what if it endangers my immortal soul? I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to come back as an earwig when I die. I want to go to heaven.

There once was a beautiful princess condemned to live the life of a peasant girl. One morning, when she was chopping wood, atiny creature sprang out. It was a little silver demon, with glowing red eyes, and it said to her, ‘Beautiful maiden, if you marry me, I will give you three wishes ...’

Tah! This axe is getting blunt. I can’t sharpen it, though, because the water is inside. And I can’t go back inside because I might overhear Navarre talking about the kind of husband she wants for me: a husband who’ll beat me thoroughly every night before we go to bed.

Oof!

There. You see? This axe is too blunt. It’s going to keep getting stuck in the wood. I hate it when the axe gets stuck in the wood. I can never pull it out; I haven’t enough strength in my arms. Where’s the maul? That might help. I could knock out the blade with the maul.

‘Psst! Babylonne!’

What—?

Oh. It’s Sybille. Hanging out of the loft window.

Just ignore her, Babylonne.

‘So you’re going to be married?’ she titters. (I

knew

she was eavesdropping.) ‘I don’t envy you your husband. Ugh!’

‘What do you mean?’ They can’t have made a decision! Not yet! ‘What husband?’

Titter, titter.

‘What husband?’

You smirking slab of pig’s tripe! ‘Tell me!’

She does, because she wants to. She’s dying to. I can see it in her face.

‘He’s a relative of Pons Saquet,’ she says. ‘He lives out near Lanta, and he’s so old that he won’t imperil your immortal soul.’ Titter. ‘You know.’ She lowers her voice until it’s a hiss. ‘With

fornication

‘You mean—he’s impotent?’

‘He’s ancient.’ She snickers behind her hand. ‘He keeps seeing giant olives bouncing around his bed.’

Oh no. Not the giant olive man. I’ve heard Lombarda de Rouaix talking about him.

‘You’ll have to feed him, and wipe his bottom, and save him from the giant olives,’ Sybille continues maliciously. ‘And then, when he dies, you’ll become his son’s servant—because what use will you be otherwise?’

Lanta. That’s a little hamlet east of here. It would be worse than Laurac.

Much

worse than Laurac.

Do they seriously expect me to spend the next ten years cleaning up after an incontinent old man in the middle of nowhere?

If so, they’re going to be sadly disappointed.

Once there was a beautiful princess whose wicked stepmother wanted her to marry an evil sorcerer. But if she did marry him, the sorcerer would cast a spell on the princess. During the day, she would turn into a donkey. Only at night would she return to her true shape.

The princess didn’t want this to happen. So she had no choice but to open her dead mother’s magic chest, and take out her dead mother’s magic boots, which would take her halfway across the world in the blink of an eye ...

Will this night never end? I seem to have been lying in bed forever.

It’s so uncomfortable, too, with all this stuff hidden underneath me. I can feel the money digging into my back: two livres tournois and a handful of Caorsins. That’s a fair share, I think. It’s much less than my dowry would be. Navarre would be losing more than two livres tournois, if I was stupid enough to stay around. And the scissors—well, I

must

have the scissors. As well as Gran’s winter hose and fur-lined boots. I mean, I can’t wear sandals, can I? And boots don’t really work without hose.

Scissors, boots, hose, money. Altogether, they’d be worth less than the dowry I’d have to pay that crazy old man and his son. It’s not as if I’m stealing. I’m just solving Navarre’s problem in another way. In a

better

way.

I can hear her snoring over there near Gran. They’re both snoring. Gran has to sleep downstairs because of the fire, and Navarre has to sleep downstairs because of Gran. As for me, I’m the one who gets clouted if the fire goes out, so I get to sleep downstairs as well.

Aaagh! Speaking of clouts, my nose is a mess. Throb, throb, throb. (Navarre can’t seem to look at me without hitting me, any more.) But it’s just as well, I suppose, or I might have fallen asleep by accident. I don’t want to miss the first cockcrow. This is my only chance. Unless I make it to the city gates before Dulcie wakes up at sunrise, I’m finished. Navarre will find out that I’ve taken the money and the scissors and the clothes from her chest, and she’ll kill me. She really will. She’ll chop me up with an axe before she can stop herself.

I have to get out of here.

A strangled sound. But the snoring resumes, and all is well. Somewhere a cricket chirps. Somewhere in the distance a baby’s crying. I can’t believe that I’ve come to this point. I can’t believe that it’s really happening. To have actually laid hands on Navarre’s keys—well, that’s a feat in itself, because she’s a notoriously light sleeper. But I did it. I snuck the keys off her belt. I opened the chest. I took out the money, and the scissors, and the clothes. And then I slid the keys back under her blankets.

If I can do all that, I can certainly do the rest. I can certainly reach the Kingdom of Aragon.

That’s the best place for me. Over in Aragon, with all the exiled

faidit

lords—the ones who lost their ancestral lands to the King of France. Like the Viscount of Carcassonne, for example. Or Olivier de Termes. I could cook for them and clean for them. I could mend clothes and throw rocks. I could help them win back Carcas-sonne and Termes from the King, and I would do it proudly. Because I would be serving those valiant knights who have never bent their knees to France. Who are

honourable

and

brave

. Unlike Bernard Oth, my cousin.

I would rather die with the noble

faidit

lords than live locked up with a useless old madman who thinks I’m a giant olive.

The princess knew what she had to do. One night, when all in the castle were sleeping, she disguised herself as a squire and escaped from her wicked stepmother. She went off to join a band of noble nights in shining armour, who had sworn to slay the venomous serpent laying waste to her country.

There! The cockcrow!

Off you go, Babylonne. Quickly, now. Quietly. Don’t make a sound. And don’t forget your bundle—you can’t go without that.

The back door creaks a bit, but it’s all right. Nobody’s moved. (Close the door behind you, remember. And watch out for that chopping block!) Already the sky is lightening, over in the east. Where are my scissors? There. Right.

Hair first.

Ouch! Yeowch! It’s harder than I thought; these scissors must need sharpening. And without a mirror, I can’t be cutting straight. I hope I don’t look too odd. I don’t want to attract attention. And what am I going to do with all this discarded hair? Stick it in my bundle, maybe. Get rid of it afterwards.

If Navarre sees it lying around on the ground, she’ll know what I’ve done. She’ll know that I’ve cut my hair short.

Now for the skirt. Knee-level, I think. It’s going to fray, but I can’t help that. Save the leftover cloth; it might be useful. Stuff it into the bundle too. In fact wrap the money in it, so that the coins won’t chink. Now for the hose. They’re not too big. I was afraid that they might be, but they could be a lot worse.

The boots smell like very, very old cheese—the kind that frightens little children. I hope they last. I have to cross the Pyrenees in these boots, and they already look as if they’re about to lie down and die.

Oh well. I have money. If I must, I’ll buy more boots.

Another cockcrow. I have to hurry, or I’m going to get caught. I won’t throw the bundle over the wall because someone might pick it up before I get to it. I’ll bring it up the woodpile with me.

Careful, now. Here’s the tricky bit. I’m not at all sure about this woodpile. I don’t think it’s very stable. And everything’s so dark, I can hardly see where I’m . . .

Whoops!

That was close. God save us, that log almost rolled out from under me! And the wood’s so noisy, too. It’s rattling. It’s crunching. It’s going to wake somebody up.