Pagan's Daughter (26 page)

When he sees me, he frowns.

‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’ he asks— but he’s not addressing me. (Corpse-breath mumbles something in my ear, the turd.) ‘Who gave you permission to leave your post?’ Loup continues, as the grip around my chest loosens. ‘What do you think this is, market-day? Who do you think you are, the Archbishop of Narbonne? Get back up on the walls!

Now!

’

Release! My feet hit the floor as Corpse-breath beats a hurried retreat; he’s smaller than I thought, and older, with a face that looks as if it’s been used as a whetstone for the last thirty years, all scored and pitted.

‘By the by,’ Loup adds, in a bored, impatient voice that he raises for the benefit of those on the stairs, ‘if you lay a hand on this one, you’ll have Pons de Villeneuve to answer to. This one’s kin to Bernard Oth.’

He nods at me before turning back to the archer. And here I am, on my own, abandoned again. What shall I do? Thank him? Slip out quietly, back into that crowd of rutting swine? Try to fetch another bucket of water?

Maybe I’d be better off with the women after all. Maybe Gerard de la Motta was right. God, I’m starting to shake. Like a triple-damned

coward

.

I can’t do this. I can’t

bear

this. I wish Isidore was here.

‘Well, it’s all fresh sinew,’ the archer is saying. ‘Useless until it’s dried . . .’

Wait. What’s that sound? Horns? Trumpets? Loup lifts his head. So does the archer. Everyone on the staircase falls silent, listening.

It’s Loup who finally speaks. In a harsh drawl that matches the crooked line of his mouth, he says, ‘Well— there’s the parley come to an end. Now at last the fight will begin.’

And his chain mail clinks as he shifts his weight to his back foot.

Once there was a beautiful princess who lived trapped in a mighty castle ...

No. On second thoughts, I don’t want to be a princess. I don’t want to live in a castle.

One morning, Babylonne woke up in her own bedroom in the house of Father Isidore Orbus. When she got dressed, she put on a pair of boots and a silk-lined gown. Then she went downstairs, where Father Isidore was waiting. He smiled and said, ‘It’s time for your reading lesson—unless you’d like to go and buy pen and ink first?’

Father Isidore. I hope he’s all right. It’s been a week, now—anything could have happened.

Lord our Heavenly Saviour, let him be all right. I’m so worried about him.

‘Oh, we’ll be fine,’ Maura’s saying. She and Grazide are sitting across the room from me, near their stone trough. But they’re not washing. They’re just sitting and talking as they delouse each other. ‘Don’t trouble yourself, Grazide, there’s nothing to be afraid of. Nothing at all.’

‘But the food can’t last forever.’ Grazide is beginning to fret. ‘What if it runs out? What if we have to surrender?’

Maura waves a careless hand. ‘Listen,’ she replies, ‘I was at the siege of Montferrand sixteen years ago. I’ve been through it all before, and let me tell you this: the garrison never comes out of it well, but people like us . . . pah!’ She clicks her fingers. ‘We’re not important enough to attract attention.’

‘But—’

‘Besides, no matter what a man’s fighting for, he always needs his washerwomen. Men are all the same—they can cook for themselves, they can draw water and milk cows and make bread if they have to, but they won’t wash clothes. I’ve never met a man yet who’ll scrub his own drawers. So don’t worry—we’re safe.’

‘But what if they start rationing water?’ It’s Dim who speaks, in his hoarse little voice. He’s been hanging around a lot—I don’t know why. I don’t know who he belongs to, or where he comes from. He just seems to spend most of his time curled up near the laundry woodpile. ‘I’ve heard that the water in the well might get low,’ he adds. ‘What if you can’t wash clothes any more?’

‘Then we’ll find something else to do,’ Maura retorts. ‘We’ll empty crap-buckets or scrape blood off the walls. Don’t worry—there’ll always be some unpleasant job that no one else wants to get stuck with. You watch.’

Suddenly she stops, listening hard. It’s that singing again, faint and sweet. The Roman priests must be marching around outside the walls barefoot, singing their Latin songs. I saw them at it the day before yesterday, when I was up on the ramparts bringing rocks to hurl at the French.

God, I’m so tired.

‘There they go,’ says Maura, straining to catch the sound of the distant chorus. ‘You’d think they’d have better things to do.’

‘It’s the same time every day, have you noticed?’ Grazide remarks. ‘I wonder why?’

Maura shrugs. ‘Personally, I don’t mind it,’ she confesses, turning her attention to Grazide’s scalp. ‘I wish they’d change their tune, though. Sing something a bit livelier. Like “The Red-combed Cock”, for instance.’

She and Grazide laugh, the way they always do when they hear a smutty joke. Grazide actually starts to sing about a red-combed cock perching in a lady’s chamber, but she stops suddenly as someone sticks his head through the door.

Whoops! It’s Gerard de la Motta.

With any luck he won’t see me, though. I chose this seat deliberately, because I’m shielded by a great big pile of dirty washing.

‘Are you looking for Babylonne, Master?’ Maura says cheerfully. ‘She’s not here, I’m afraid.’

‘Are you sure?’ I can’t see Gerard’s face any more, but he sounds suspicious. ‘She doesn’t seem to be anywhere else.’

‘You can have a look if you like.’ Maura farts before continuing. ‘Mind those silk drawers, though. If you touch ’em when they’re wet, it will leave a stain. And I just cleaned all the stains off.’

‘Um—er—no, that’s all right,’ Gerard mutters. There’s a brief silence, broken at last by Grazide’s guffaw.

‘ “If you touch ’em when they’re wet, it will leave a stain”,’

she chuckles. ‘You’re a dirty sow, Maura!’

‘It’s not my fault if he’s got a lecher’s mind,’ Maura rejoins. ‘Where’s the girl? Babs, my poppet, he’s gone now. You can come out if you like.’

Thank you, God. That’s the second time today. Why can’t he leave me

alone

?

‘If you want to know what I think, I think he’s got a yen for you, my Babsy,’ Maura continues, flicking a dead louse off her thumb. ‘Otherwise he wouldn’t always be chasing you around.’

‘It’s not that.’ (Can’t you think about anything above the waist?) ‘He just doesn’t like me wandering free. He wants to keep me locked up somewhere, because he’s scared of my grandmother.’

‘Hah! Maybe that’s what he

says

,’ Maura replies. ‘They might

say

that they’re against a cuddle in the cow-byre, but they’re all cut from the same cloth.’

‘Not Good Men, though,’ Grazide objects. ‘Good Men really are chaste.’

‘Don’t you believe it.’ Maura speaks with authority. ‘They all need to plant their standards, and the less they do it, the worse they are. Good Men and Roman priests alike.’

You’re wrong, Maura. You’re wrong because you don’t know Father Isidore. Father Isidore really

is

a holy man. He doesn’t even notice if you’re a girl or a boy.

‘Anyway, if I were you, I’d keep away from those Good Men,’ Maura adds, dragging a nit out of Grazide’s hair. ‘Because if this place submits, they’ll be first in the fire.’

‘I know.’ How could I

not

know?

‘They burned ’em at Minerve. They burned ’em at Les Casses. They’ll burn ’em here,’ Maura continues, as if I never even opened my mouth. ‘There’s only one lot that ever comes out of these things worse than the garrison, and that’s the Perfects. You don’t want anybody thinking you’re one of

them

.’

CRA-A-ASH!

By the beard of Beelzebub! What was

that

? It shook the very ground—I can hear someone screaming—don’t tell me they’ve broken through!

Grazide whimpers. Even Maura frowns. Get out of my way, Dim, you stupid boy! Outside, everything’s a mess. There are people running about like startled chickens. Someone’s stretched out on the ground, and . . . ah. I see.

A rock must have come over the wall, and shattered in the middle of the bailey. That poor soul was hit by a flying splinter.

Unless I’m mistaken, the French have finally got their trebuchet to work.

‘Come on,’ says Maura, from behind me. ‘We’d better take this one up to the chapel.’ And she brushes past, shambling towards the wounded man on the ground.

I suppose I’d better help, since I’m on infirmary duty. I wish I didn’t have to, though. I hate this job. I’d rather do

anything

else. I’d rather carry sand, or draw water, or pass bolts to the men who arm the ballista, up on the walls in full view of the French. I’d rather shovel

manure

than move the wounded.

Not that there have been many wounded yet, but there will be.

‘Mercy on us,’ says Maura, as she rolls the limp figure onto his back. God’s death! That’s too . . . that’s too much. I can’t look.

He’s lost half his face.

CRA-A-ASH!

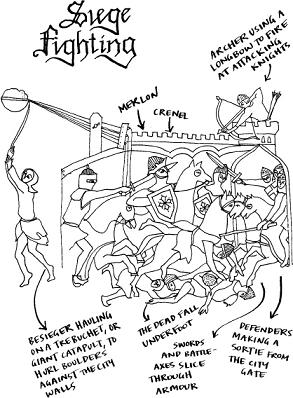

Help! Another one! But it didn’t sound close—it must have hit the wall. Yes, up there. It must have knocked a merlon off the ramparts.

‘Come

on

!’ Maura snaps. ‘Take his feet, will you?’

Take his feet. Yes. There’s nothing wrong with his feet. If I keep my eyes fixed firmly on his feet, I won’t be sick. Someone’s still screaming somewhere, and here comes Olivier, running across the bailey. He’s pulling a surcoat on over his chain mail, which chinks with each step. He has the ruffled hair and creased face of a man who’s just woken from a heavy sleep.

If he’s been sleeping, things can’t be too bad. Can they?

Vasco is with him.

‘. . . aimed at the weakest point,’ Vasco’s saying. ‘But they’re firing wide.’

‘We have to get out there somehow,’ Olivier mutters.

‘Get out there and burn it.’

‘Move, you slug!’ says Maura, and she’s talking to me. Right. Of course. This is no time to stand and stare. As we shuffle towards the keep, I can hear somebody crying. I can see shards of rock scattered around— shards that might be useful, if they’re collected. All the children should be made to collect those chips of rock.

Suddenly, the wounded man whimpers.

‘It’s all right, my lad,’ says Maura. (At least he’s alive.) Inside the keep, there aren’t many people. The Great Hall’s practically empty; everyone must be up on the walls. I recognise the soldier who’s asleep on a pile of straw under a bench. He’s the one who took my Caorsin from me by the well, a couple of days ago.

Doesn’t he

ever

do any work?

CRA-A-ASH!

Another missile. Closer, this time. God preserve us.

‘The French are in a hurry,’ Maura wheezes. The wounded man gurgles with each breath, and it’s a terrible sound. I’d rather hear rocks hitting the walls. At the base of the stairs, Maura shifts her burden. She’s beginning to pant. ‘Got him?’ she asks.

‘Yes.’

‘Not much farther.’

Maybe not, but what good will it do? This man is dying, I’m sure of it. And taking him to Gerard de la Motta won’t help. On the contrary. Gerard’s no physician.

If these stairs don’t kill the poor wretch, Gerard de la Motta certainly will.

‘Make way!’ yells Maura—because who knows what careless fool might be hurtling down towards us? Oof! I must be bearing most of the weight now, and it’s quite a load. He’s a big man, this one; his feet are as long as my forearm. We’re leaving a trail of blood behind us. (Somebody’s bound to slip on it.) And here we are at the chapel.

At last.

‘We’ve got another!’ Maura announces, for the benefit of the Perfects who turn to watch us come in. ‘Where do you want him?’

I’d be laughing, if I wasn’t so heartsick. Look at the way they all cringe at the sight of Maura’s huge, bouncing body and sweaty face! Only the old Gascon sergeant wearing homespun doesn’t seem to notice Maura. He’s more interested in what she’s carrying.

‘Who is it?’ he asks in his thick, crunchy voice. (It’s like the sound of seeds being ground in a pestle.) ‘Does anyone know?’

No one does. At least, no one says anything. Certainly not the half-dozen men lying on the floor, who are probably incapable of speech anyway. The amputee by the altar will never talk again, in my opinion. He’s dying. You can smell his stump from way over here; Peitavin’s been left beside him, to flap the flies away. The rest of the patients simply twitch and moan, or lie unconscious, their faces the colour of tallow.

Gerard de la Motta ignores them, however. He’s not interested in their suffering. He’s far more interested in mine.

‘Where have you been?’ he demands, scowling at me. ‘I told you to stay here. At your post.’

‘I felt sick.’ This whole place makes me sick. You, especially. ‘I had to get some air.’

‘Put him over here,’ the old sergeant commands, taking charge. ‘That’s it. Gently.’

‘You shouldn’t wander about, Babylonne.’ Gerard’s still nagging. ‘Why should you do such a thing? Are you

courting

the attention of lewd men?’

Oh, will you shut

up

? ‘I’m bringing in the wounded!’ (In case you haven’t noticed!) ‘Can you help me, please? Before I drop this man?’