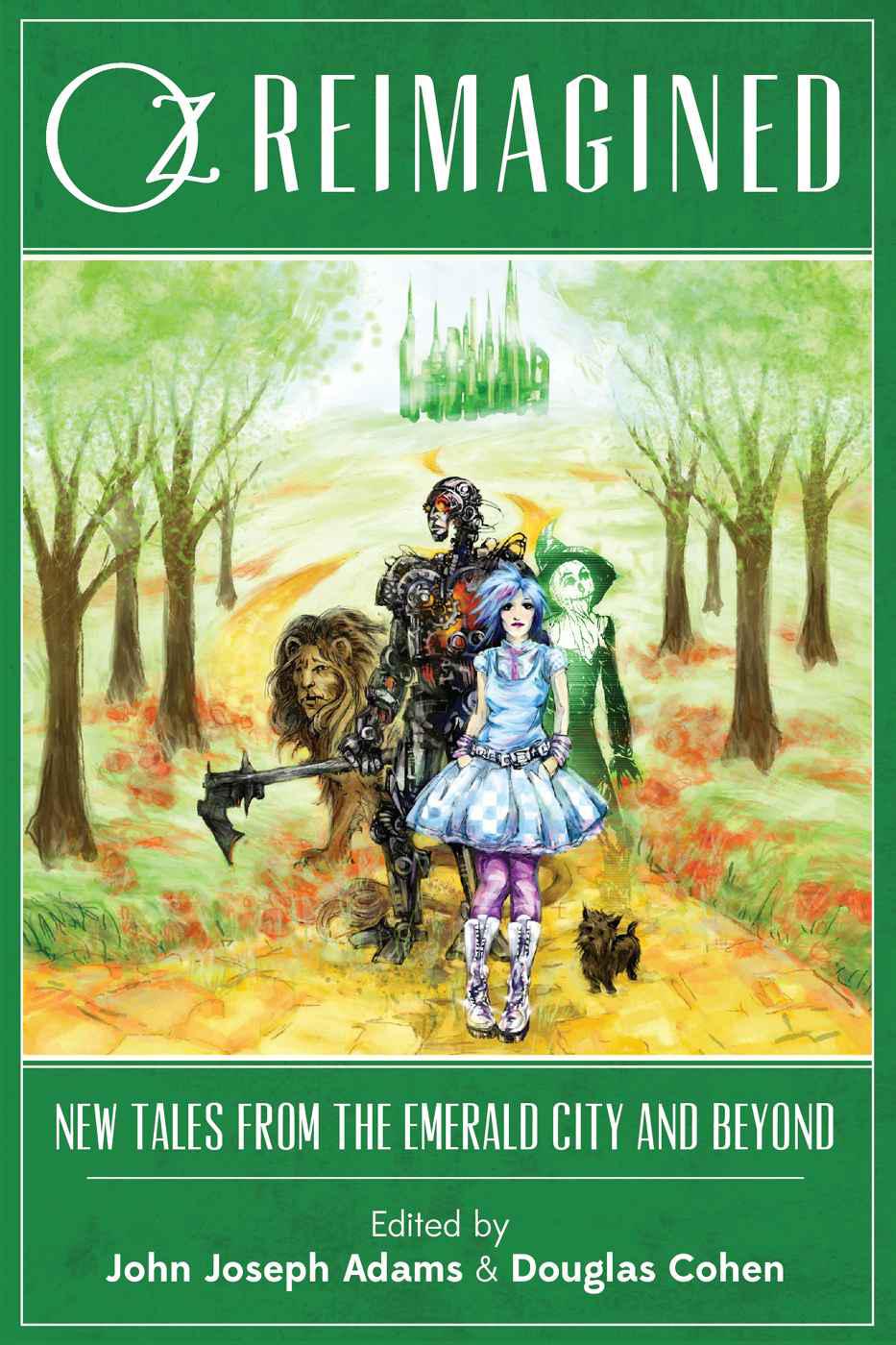

Oz Reimagined: New Tales from the Emerald City and Beyond

Also Edited by John Joseph Adams

Armored

Brave New Worlds

By Blood We Live

Epic: Legends of Fantasy

Federations

The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Lightspeed Magazine

Lightspeed: Year One

The Living Dead

The Living Dead 2

The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination

Nightmare Magazine

Other Worlds Than These

Seeds of Change

Under the Moons of Mars: New Adventures on Barsoom

Wastelands

The Way of the Wizard

Forthcoming Anthologies Edited by John Joseph Adams

Dead Man’s Hand

Robot Uprisings

(co-edited with Daniel H. Wilson)

Wastelands 2

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2013 by John Joseph Adams & Douglas Cohen

“Foreword: Oz and Ourselves” by Gregory Maguire. © 2013 by Gregory Maguire.

“Introduction: There’s No Place Like Oz” by John Joseph Adams & Douglas Cohen. © 2013 by John Joseph Adams & Douglas Cohen.

“The Great Zeppelin Heist of Oz” by Rae Carson & C.C. Finlay. © 2013 by Rae Carson & C.C. Finlay.

“Emeralds to Emeralds, Dust to Dust” by Seanan McGuire. © 2013 by Seanan McGuire.

“Lost Girls of Oz” by Theodora Goss. © 2013 by Theodora Goss.

“The Boy Detective of Oz: An Otherland Story” by Tad Williams. © 2013 by Tad Williams.

“Dorothy Dreams” by Simon R. Green. © 2013 by Simon R. Green.

“Dead Blue” by David Farland. © 2013 by David Farland.

“One Flew Over the Rainbow” by Robin Wasserman. © 2013 by Robin Wasserman.

“The Veiled Shanghai” by Ken Liu. © 2013 by Ken Liu.

“Beyond the Naked Eye” by Rachel Swirsky. © 2013 by Rachel Swirsky.

“A Tornado of Dorothys” by Kat Howard. © 2013 by Kat Howard.

“Blown Away” by Jane Yolen. © 2013 by Jane Yolen.

“City So Bright” by Dale Bailey. © 2013 by Dale Bailey.

“Off to See the Emperor” by Orson Scott Card. © 2013 by Orson Scott Card.

“A Meeting in Oz” by Jeffrey Ford. © 2013 by Jeffrey Ford.

“The Cobbler of Oz” by Jonathan Maberry. © 2013 by Jonathan Maberry Productions, LLC.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by 47North

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781611099041

ISBN-10: 1611099048

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012953172

Dedication

For that wonderful wizard,

L. Frank Baum

L. Frank Baum’s original Oz books were works of children’s fiction—albeit ones that have been known and loved by “children of all ages” throughout their existence. Though many of the stories contained in this anthology are also suitable for the aforementioned children of all ages,

Oz Reimagined

is intended for ages thirteen and up, and as such, some of the stories deal with mature themes, so parental guidance is suggested.

Foreword: Oz and Ourselves by Gregory Maguire

Introduction: There’s No Place Like Oz by John Joseph Adams & Douglas Cohen

The Great Zeppelin Heist of Oz by Rae Carson & C.C. Finlay

Emeralds to Emeralds, Dust to Dust by Seanan McGuire

Lost Girls of Oz by Theodora Goss

The Boy Detective of Oz: An Otherland Story by Tad Williams

Dorothy Dreams by Simon R. Green

One Flew Over the Rainbow by Robin Wasserman

The Veiled Shanghai by Ken Liu

Beyond the Naked Eye by Rachel Swirsky

A Tornado of Dorothys by Kat Howard

Off to See the Emperor by Orson Scott Card

A Meeting in Oz by Jeffrey Ford

The Cobbler of Oz by Jonathan Maberry

BY GREGORY MAGUIRE

W

hen I try to settle upon some approach to the notion of Oz that might suit many different readers, and not just myself, I stumble upon a problem. The unit of measure that works for me might not work for you. Standards and definitions vary from person to person. Oz is nonsense; Oz is musical; Oz is satire; Oz is fantasy; Oz is brilliant; Oz is vaudeville; Oz is obvious. Oz is secret.

Look: imagine waiting at a bus stop with a friend. We’re both trying to convey something to each other about childhood. When you say

childhood

, do you mean “childhood as the species lives it”? Do I mean “my childhood upstate in the mid-twentieth century, my house on the north edge of town, my grouchy father, my lost duckie with the red wheels”?

Oz comes to us early in our lives, I think—maybe even in our dreams. It has no name way back then, just “the other place.” It’s the unspecified site of adventures of the fledgling hero, the battleground for the working out of early dilemmas, and the garden of future delights yet unnamed.

Foreign and familiar at the same time.

Dream space.

Lewis Carroll called it Wonderland, Shakespeare called it the Forest of Arden, the Breton troubadours called it Broceliande, and the Freudians called it Traum. The Greeks called it Theater, except for Plato, who called it Reality. Before we study history, though, before we learn ideas, we

know

childhood through our living of it. And for a century or so, we Americans have called that zone of mystery by the name of Oz.

Your little clutch of postcards from the beyond is a different set than mine, of course. Nobody collects the same souvenirs from any trip, from any life. Yours might be the set derived from those hardcovers in your grandmother’s attic, the ones with the John R. Neill line drawings someone colored over in oily Crayola markings. (Crayons were invented at just about the same time as Oz, early in the twentieth century.) Or your souvenir cards might be the popular MGM set starring Margaret Hamilton and Bert Lahr and some child star—I forget her name. Or your souvenirs might be more like mine: memories of being a kid and reenacting (and expanding upon) the adventures of Dorothy using the terrain at hand, which in my case was a filthy alleyway between close-set houses in the early 1960s. Dorothy in her blue-checked gingham and her pigtails is my baby sister in her brother’s T-shirt, hair all unbrushed and eyes bright with play.

What, I wonder, did we Americans do to conjure up a universal land of childhood before L. Frank Baum introduced us to Oz? Did the Bavarian forests of Grimm or the English fairylands (sprites and elves beckoning from stands of foxgloves, deep hedgerows) ever quite work for American kids? Or maybe that’s a silly question. Perhaps before 1900—when

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

was first published and the United States was still essentially rural and therefore by definition hardscrabble—there was no time to identify the signposts of childhood. Children’s rooms in public

libraries hadn’t yet been established. Reading for pleasure wasn’t for everyone, just for those who could afford their own private books. Few nineteenth-century Americans could relish childhood as a space of play and freedom; instead, childhood was merely the first decade in a life of hard toil on the farm or the factory.

Maybe Oz arose and took hold because urban life began to win out over rural life. Maybe as our horizons became more built up and our childhoods—for some middle-class American kids anyway—a little more free, the Oz that came to us first on the page and later on the screen had a better chance of standing in for childhood. That merry old Land of Oz certainly did, and does, signify childhood for me; I mean this not as the author of

Wicked

and a few other books in that series, but as a man nearing sixty who recognized in Oz, more than half a century ago, a picture of home.

I don’t mean to be sentimental. There’s a lot to mistrust about home. It’s one of the best reasons for growing up: to get away, to make your own bargain with life, and then to look back upon what terms you accepted because you knew no better, and to assess their value. Travel is broadening precisely because it is

away from

as well as

toward

.

As a young man, on my first trip abroad, I went to visit relatives in northern Greece, where my mother’s family originates. In the great Balkan upheavals of the last century, the boundaries of political borders had shifted a dozen times, and the family village that had once been part of Greece, in the early twentieth century, lay now in Yugoslavia—still a Communist country in the late 1970s when I first saw it. Stony, poor, oppressed. My ancient, distant relatives, all peasant widows in black coats and neat headscarves, told me how their mother had spent her married life imprisoned in Thessaloniki, Greece, on the top edge of the Aegean; but, of a fine

Sunday afternoon, she would direct her husband to drive her north, to a hillside just this side of the border of Yugoslavia. There she would sit by the side of the road and weep. The village of her childhood was on the other side of the border crossing. From this height she could see it, like Moses examining the Promised Land, but she was not allowed back. She could never go back. She never did, or not in this life, anyway. She never sent us postcards once she finally crossed over.

Oz lives contiguously with us. The Yellow Brick Road, the Emerald City, and the great Witch’s castle to the west—these haunts are more than tourist traps and hamburger stands. They are this century’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Via Dolorosa and Valhalla. Oz is myriad as the Mediterranean with its spotted Homeric islands; Oz is vast as Middle-earth and moral as Camelot. This is to say, of course, that Oz is a mirror. Turn it about and, in the mirror,

OZ

nearly says

ZOE

, the Greek word for life.

Of course we recognize Oz when we see it. Of course we find ourselves there. If we can’t find ourselves

there

, well, we don’t have much chance of recognizing ourselves

here

. As some farmhand or other might have said to Dorothy, or she to the Wizard.