Oxfordshire Folktales (23 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

![]()

T

HE

L

EGEND

OF

S

T

F

REMUND

King Offa of Mercia had a son called Fremund, who he had high hopes for – as the Crown Prince, one day the kingdom would be his. But Fremund was a strong-willed boy and when it reached the time when he needed to shoulder some responsibility, he fled. Royal life had always been cloying for him – there was something about the endless feasting and finery that just didn’t agree with him. He preferred his own company; prayer; or walking in nature. He was sick at heart of the bloodthirsty times he lived in. The Law of the Sword did not appeal to him as much as the Word of the Lord.

One day, he decided to give it all up. He set sail with twelve companions, brothers and kindred spirits, in a birlinn from Caerleon-on-Usk, eventually landing at ‘llefaye’ – a small rocky island in the mouth of the Severn which was home to a colony of puffins and little else. It had a harsh beauty of its own and it suited his temperament. Here he established a hermitage and began a simple, devout life.

On the other side of the isle of Britain, things were not so tranquil. Viking invaders had swept across East Anglia, martyring King Edmund. The Mercian people were headless – for King Offa had died – and so, in desperation, a group were sent in search of the lost prince. It was Mercia’s darkest hour and a leader was needed.

The emissaries found Fremund upon the small island, leading a peaceful, contemplative life. They pleaded with him to return. Why should he? Well, it was his own people, his own land. If he had any honour, how could he forsake it? And so, finally, he accepted. He had put aside the sword – but now he had to seize it and become a leader. Steeling himself, he put aside his monk’s robes and put on his armour. Leaving his pilgrim staff on the island, as they put out in a small boat for the mainland, he unsheathed the sword and held it aloft in the morning light.

In haste and secrecy, they returned to Mercia.

Fremund, son of Offa, rallied his people and led them in a victorious battle at Radford Semele. His father would have been proud of his heir.

Alas, as Fremund knelt in prayer to give thanks for his victory, one of his own men struck off his head. Some say he was envious, but perhaps other forces influenced him – was he a turncoat; a Viking assassin; or had Old Nick himself possessed him?

As his followers looked on, aghast at the tragedy, something astonishing happened. Fremund’s headless corpse twitched into life, blood still flowing from the gaping wound of the neck. The body stood up and picked its head and began to walk. The onlookers were too stunned to react, they could only follow as the headless Fremund walked and walked – until he eventually stopped between Harbury and Whitton. From beneath his very feet a well sprang up, flowing with good, clean water. Fremund then began to wash his own head, cleaning it of the blood from battle. When he had finished, a sigh escaped his ruined corpse and he finally lay down and died.

When his followers recovered from witnessing this miracle, Fremund’s remains were taken to the church of Offchurch in Warwickshire. This became a shrine for all those wanting healing. In

AD

93, the relics were taken to Cropredy in Oxfordshire. Here they remained, in a chapel, until the thirteenth century, when they were once more moved to Dunstable. Yet Cropredy, having been so long associated with the saint, retained its sanctity and importance as a place of pilgrimage. It was only during the Civil War that his shrine was destroyed by Cromwell’s army.

No sign of the shrine remains, but Fremund’s spirit perhaps still lingers in the village of the stream by the hill.

![]()

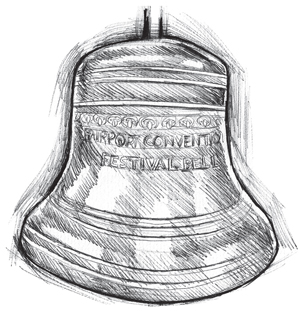

The village has become a modern place of pilgrimage, as every year thousands of folk music fans gather for the annual Cropredy Festival – the Fairport Convention reunion. For over forty years – since the band formed in 1967 – friends have gathered here, and to mark four decades of association with the village the band paid for a Festival Bell to be cast, which now hangs in the local church, calling new worshippers to this little village in the northernmost tip of Oxfordshire. Perhaps St Fremund would have approved – his head swaying like the bell in time to the music of the life.

Y

OUNG

A

LFRED

, S

ON

OF

W

ANTAGE

Sometimes, the littlest things can become the greatest.

Alfred was the youngest son of Aethelwulf and his wife, Osberga. He was born at the Royal Palace of Wantage in

AD

849. The older folk called it Gwynedd-iog, or ‘White Hills Place’ – after the chalk downs that rose to the South. Yet the old tongue was discouraged. A new tide was sweeping the land, forged in the clash between the Cross and the Hammer.

It was a dangerous world for a small boy to grow up in, but the young prince – oblivious to the turmoil beyond the walls of White Hills Place – found it exciting. His local landscape seemed carved for adventure.

Alfred’s hometown had once been the place of two rivers but one had faded away, so it was referred to as ‘waning river’ in the common Saxon tongue and, over time, it became known as Wantage. Young Alfred pondered whether one river had subsumed the other, or if they had mingled together – it was hard to tell, as he gazed into the waters of Letcombe Brook one day. He reflected how King Arthur had fought against Alfred’s own people when they were considered the invaders, and yet here they were, fighting off the new wave – the Danelaw Vikings – sweeping in from the East. Withstanding this were the white hills of Wantage: here his father’s shining palace stood like a pale sword against the night – a Saxon Minster; home of a long line of kings, of which Alfred was descended.

Alfred wondered where Aetheldred was. They were due at the feast and his brother was always late for things! Yet he loved his older brother; growing up they had been inseparable; but Alfred sensed a change in Aetheldred these days – moping about or restless, as though waiting for something, something that would change their lives forever.

The wyrd had singled out a special fate for both of them. Their father had instilled into them this noble destiny, saying they were descended from the old gods – Woden, Sceaf and Geat. He would insist they honoured them in their prayers in the groves and by the river. Their ancestors had brought these gods with them to these lands and now this land was theirs. Alfred felt closest to them at a spring he liked to bathe in on the edge of the settlement. Here, he communed with the water spirits. He felt safe – in the water nothing could touch him.

He would remember that feeling in years to come.

Alfred saw little of his father – a King is always busy – and was brought up and educated by his mother. Once, she had promised an expensive illuminated book to the first of her children to learn it by heart. Despite his young age – he was only five at the time – Alfred committed it to memory and won the prize. He treasured that book and loved looking through its colourful pictures, telling stories of kings from long ago. He grew to love all books and the gathering of knowledge. You could learn from the past – it helped you prepare for the future, yet some things are unseen.

When Alfred was sixteen, his father died. It was

AD

865 and his older brother, Aethelred, became King of Wessex. The funeral was befitting a king, as was the coronation. Alfred stood by his brother’s side – pride mixed with grief.

The wheel turned.

The young prince grew into his body. His limbs lengthened and hardened; his skill with sword and spear improved. No one could catch him on horseback – it was as though he was one with the animal – but faster still were his wits. He honed these like a sword – he had a kingdom to defend.

Alfred quickly became a seasoned warrior and his brother’s right-hand man during one of the worst periods of invasion in English history.

The Vikings had been raiding along the English coast for thirty years, but in Aethelred’s coronation year they conquered the Kingdom of East Anglia.

Within five years, their Great Heathen Army had arrived in Wessex and seized the Royal palace at Reading, in Berkshire. The local ealdorman managed to contain them until the King arrived with Alfred and the English army. The attempted siege at Reading was unsuccessful.

Soon afterward, in January

AD

871, Alfred regrouped his brother’s troops on the nearby Berkshire Downs. Riding to the top of Blowingstone Hill, Alfred made use of an ancient perforated sarsen stone; known as the ‘Blowing Stone’, it was capable of producing a loud, booming sound when blown into correctly. With the signal sent out across the downs, he rode to a hill-fort near Ashdown House to gather his men; while Aethelred’s men rallied at nearby Hardwell Camp. Uniting their forces, Aethelred and Alfred learned that the Danes had encamped at nearby Uffington Castle.

Alfred’s men gathered at the castle that now bears his name in the parish of Ashbury. Aethelred’s troops had taken up position not far away at Hardwell Camp (these days known as Compton Beauchamp). Meanwhile, the Danes had reached Uffington Castle, where they settled down for the night.