Overlord (Pan Military Classics) (55 page)

Read Overlord (Pan Military Classics) Online

Authors: Max Hastings

The episode that prompted the sackings, the fumbling of BLUECOAT, was characterized by many of the misfortunes that befell the British that summer, and deprived them in the eyes of the Americans of the credit that was justly theirs for bearing so thankless a burden on the eastern flank. It began with the usual confident, even cocky, letter from Montgomery to Eisenhower: ‘I have ordered Dempsey to throw all caution overboard and to take any risks he likes, and to accept any casualties, and to step on the gas for Vire.’

3

On 30 July, O’Connor’s VIII Corps drove hard for Le Bény Bocage and Vire along the boundary with the American XIX Corps, while on their left XXX Corps made for the 1,100-foot summit of Mont Pinçon. Roberts’s 11th Armoured – by now established as the outstanding British tank division in Normandy – made fast going and seized the high ground of Le Bény Bocage, at the vulnerable junction between Panzer Group West and Seventh

Army. Boundaries are critical weak points in all formations in all armies, the seams in the garment of defence. It has been suggested in recent years

4

that Montgomery missed a great opportunity by failing to push through here, seize Vire and roll up Seventh Army instead of leaving Vire to the American XIX Corps. When 11th Armoured approached the town before obeying orders to turn south-east on 2 August, it was virtually undefended. But by the time the Americans moved against it the Germans had rushed in troops to plug the gap, mounted vigorous counter-attacks, and were only finally dispossessed on the night of 6 August. Once again, the line had congealed.

But Montgomery and Dempsey’s attention in the first days of August was focused upon the new failure of 7th Armoured. Bucknall was warned to reach Aunay-sur-Odon quickly, or face the consequences. After two days of BLUECOAT he was still five miles short. Montgomery acted at last – belatedly, in the view of much of his staff, particularly his Chief of Staff, de Guingand, who was far more sensitive than his Commander-in-Chief to the prevailing scepticism about the British at SHAEF.

In the days that followed, Second Army continued to push forward south-east of Caumont, gaining a few miles a day by hard labour and hard fighting. Tank and infantry co-operation was now much improved, with the armoured divisions reorganized to integrate tanks and foot-soldiers within their brigades. Since GOODWOOD, it had at last become accepted tactical practice for infantry to ride forward clinging to the tanks when there were suitable opportunities for them to do so. If there was less of the flamboyant spirit of the landings, there was much more professionalism. Most of the Scottish units, which in June so eagerly sent forward their pipers to lead the men into battle, had long ago dispensed with such frivolities by August. Too many pipers would never play another pibroch.

But for the men among the corn and the hedges, each morning seemed to bring only another start-line, another tramp through

incessant mortar and shellfire, coated in dust, to another ruined village from which the Germans had to be forced by nerve-racking house-clearing.

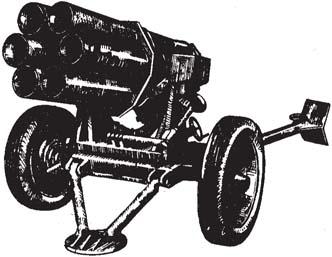

The war artist Thomas Hennell wrote late in July of ‘the sense-haunted ground’ the armies left in their wake. ‘The shot-threshed foliage of the apple orchards was fading and just turning rusty, fruit glowed against the sky; there were ashes of burnt metal, yellow splintered wood and charred brown hedge among the shell pits; every few yards a sooty, disintegrated hulk . . .’ The equipment in the hands of von Kluge’s armies was perfectly suited to generating maximum firepower with minimum manpower. The multi-barrelled mortar, employed in powerful concentrations, was a devastating weapon against advancing infantry. By August, British artillery was making intense efforts to grapple with the problem by creating specialist counter-mortar teams. The surviving German tanks were as resistant as ever to Allied penetration. A sergeant-major of the KOSB received a well-earned Military Cross for knocking out an enemy Panther which endured six hits from his PIAT before succumbing. The fields at evening were landmarked with upturned rifles jammed in the earth to mark the dead. The tank crews cursed the ripened apples that cascaded into their turrets as they crashed through orchards, jamming the traverses, while the shock of repeated impacts on banks and ditches threw their radios off net. The Germans had lost none of their skill in rushing forward improvised battle-groups to fill sudden weaknesses that were exposed. Again and again, British scout cars or tanks reported an apparent gap which might be exploited, only to find it filled before an advance in strength could be made. 15th Scottish Division signalled one of its battalions one evening that Guards Armoured had reported a withdrawal by the enemy on their front. The infantry must ensure that they patrolled to avoid losing contact. An acerbic message came back from the company commander on the front line, that since he was at that moment engaged in a fierce close-quarter grenade battle, there was scant need for

patrolling to discover where the enemy was. But another German skill, much in evidence in those days, was that of disengagement: fighting hard for a position until the last possible moment, then breaking away through the countryside to create another line a mile or two back, presenting the British yet again with the interminable problems of ground and momentum.

You turn off the main road to Vire at Point 218 and go down a side road to the top of a ridge [Lieutenant Richard Mosse, commanding 1st Welsh Guards Anti-Tank Platoon, described his battalion’s position on 8 August]. ‘Dust means shells’ notices were in great evidence. It was the worst place I have ever been in. Numerous bodies of our predecessors lay in the fields between the companies, with about 25 knocked out vehicles, mostly British. A thick dust covered everything, and over it all hung that sweet sickly smell of death. By day we could not move as we were under observed mortar fire, and going up to the forward companies under machine-gun fire at times . . . August 12 brought news that our guns had opened short again, and Sgt. Lentle and one other had been killed and several wounded. Sgt. Lentle I could ill afford to lose. He was a steady, sensible man. He would not take risks, he had a wife and two boys he adored, but he would obey any order however dangerous. I could always rely on him . . . David Rhys, the mortar platoon commander, was wounded. Hugh, Fred and I were all that was left in the company, so we helped hold a bit of the line. We had advanced some half a mile; our casualties were 122, 35 killed . . . As long as I live that word

bocage

will haunt me, with memories of ruined countryside, dust, orchards, sunken lanes and the silly little shoots that were all I could find for the guns.

Mosse’s description of his battalion’s predicament is a sober corrective for those who suppose that by the middle days of August, with the German army in Normandy within a week of collapse,

the pressure upon their opponents was easing. The pain and the constant drain of losses persisted to the bitter end.

On the night of 7 August, preceded by a massive air attack by Bomber Command, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds launched his II Canadian Corps on a renewed offensive southwards towards Falaise: Operation TOTALIZE. Simonds, who had commanded a division in Sicily, was to prove one of the outstanding Allied corps commanders in Europe, a dour, direct officer who brought unusual imagination to bear on every operational plan for which he was responsible. It was Simonds who now decided to make his attack across open country in darkness, to use 76 converted self-propelled gun-mountings to move his lead infantry, and to employ a sophisticated range of electronics and illuminants to guide his men to their objectives through the night. There was to be no delay in following up the bombers.

Even as the planning for TOTALIZE was being carried out, von Kluge’s redeployment for Mortain was taking place. 9th SS Panzer retired from the British front on 1 August, followed by 1st SS Panzer on the night of the 4th, to be relieved by 89th Infantry. A Yugoslav deserter from the 89th reached the Canadian lines almost immediately, bringing this information to Simonds. For the first time since 7 June, the weight of the German army had been lifted from the eastern flank. On Crerar’s right, 43rd Division had at last cleared the heights of Mont Pinçon in a fine action on 6/7 August, and the 59th Division was across the Orne north of Thury–Harcourt. The Germans’ left front was thus already under heavy pressure when the Canadians moved.

At 11.30 p.m. on 7 August, the assault forces crossed the start-line, led by navigating tanks and flails. They rumbled forward, in four columns of four vehicles abreast, into the great dust cloud raised by the bombing. Bomber Command had done its job, guided by coloured marker shells, with astonishing accuracy – there were no casualties among Allied troops and 3,462 tons of bombs had

fallen on the villages in the path of the attack. There was no preliminary artillery bombardment. For the men on the ground, the spectacle was astonishing, with searchlights directed towards the clouds – ‘Monty moonlight’ – being used to improve visibility, and Bofors guns firing tracer to mark the axes of advance. Their early progress was encouraging. Despite collisions and navigation errors, the early objectives had fallen by first light. 51st Highland Division on the left were making good ground, leaving much mopping-up to the follow-up units. German counter-attacks were repulsed, and 2nd TAF’s Typhoons were out in strength, aided by Mustangs and Spitfires flying sweeps over German approach roads. At about 12.50 p.m., the first of 492 Fortresses of 8th Air Force began to launch a new wave of support attacks. The bombing was wild. The Canadians, British and Poles beneath suffered over 300 casualties. The men below on the ground were enraged. ‘We asked – how the hell could they fail to read a map on a clear day like this?’ said Corporal Dick Raymond of 3rd Canadian Division. ‘A lot of our guns opened up on the Fortresses. When they hit one, everybody cheered.’

Now came the familiar, depressing indications of an offensive losing steam. Tilly-la-Campagne still held. As so often throughout the campaign, German positions which had been bypassed, and which it was assumed would quickly collapse when they found themselves cut off, continued to resist fiercely. II Canadian Corps had advanced more than six miles, but Falaise still lay 12 miles ahead. Night attacks by Canadian battle-groups were driven back with substantial loss. The familiar screens of 88mm guns inflicted punishing losses upon advancing armour. Meyer’s battered units of 12th SS Panzer had been under orders to move westwards when TOTALIZE was launched, but were thrown quickly into the line to support 89th Infantry. 12th SS still possessed 48 tanks of its own, and also had 19 Tigers of 101st SS Heavy Tank Battalion under its command. Although his formation was out of the line when the Canadian attack began, Meyer had left liaison officers at the front who were able to report to him immediately. Early on 8 August,

battle-groups Waldmuller and Krause of 12th SS Panzer – the latter hastily switched from the Thury–Harcourt front – drove into action around the Falaise road. It was in the fierce fighting which now developed that Michael Wittman, the German hero of Villers-Bocage and the greatest tank ace of the war, at last met his end amid concentrated fire from Shermans of ‘A’ squadron, Northamptonshire Yeomanry.

Both the Polish and Canadian armoured divisions spearheading the Allied attacks were in action for the first time, and this undoubtedly worsened their difficulties and hesitations. On the night of 8 August, Simonds ordered the tanks to press on with erations through the darkness. Many units simply ignored him, and withdrew to night harbours in the manner to which they were accustomed. The few elements which pressed on regardless found themselves isolated and unsupported, and were destroyed by the German 88 mm guns. On 9 August, Simonds’s staff were exasperated by the persistent delays that appeared to afflict almost every unit movement, the repeated episodes of troops and tanks firing on each other, the difficulty of getting accurate reports from the front about what was taking place. A fierce German counterattack by a battle-group of 12th SS Panzer completed the chaos. The British Columbia Regiment lost almost its entire strength, 47 tanks in the day, together with 112 casualties. The infantry of the Algonquins, who had been with them, lost 128. The Poles on the left made some progress, getting through to St Sylvain. On the night of the 9th the Canadian 10th Brigade made good progress further west. But after accomplishing little during the day of 10 August, a major night attack on Quesnay woods by 3rd Canadian Division ended in its withdrawal early the following morning.

The Canadians’ enthusiasm was obviously waning; difficulties at higher headquarters compounded uncertainty on the ground. Montgomery had always lacked confidence in Crerar, the Canadian army commander, and much upset the Canadians at the outset of this, their first battle as an army, by sending his own staff officers from 21st Army Group to Canadian headquarters to oversee their

performance. Crerar became locked in dispute with the rugged Crocker, the British I Corps commander, whom he attempted to sack on the spot. An impatient Montgomery sought to persuade both men to focus their animosity upon the enemy. ‘The basic cause was Harry. I fear he thinks he is a great soldier, and he was determined to show it the moment he took over command at 1200 on 23 July. He made his first mistake at 1205; and his second after lunch . . .’

5

It is an astounding reflection upon the relative weight of forces engaged north of Falaise that by the night of 10 August, the German tank strength was reduced to 35 (15 Mk IV, five Panther, 15 Tiger), while the Canadian II Corps, even after losses, mustered around 700. Yet on 10 August, with some German reinforcements moving onto the front, it was decided that nothing less than a full-scale, set-piece attack with massed bomber preparation would break the Canadians through to Falaise. The defenders had shown their usual skill in shifting such armour and anti-tank guns as they possessed quickly from threatened point to point, presenting strong resistance to each successive Canadian push. It was also evident that the Canadians were not performing well. Because their government, until very late in the war, would ask only volunteers to serve overseas, it had great difficulty in maintaining First Canadian Army at anything like its establishment level. Many men on the battlefield were embittered by the feeling that the Canadian nation as a whole was not sharing their sacrifice. The best of Crerar’s troops were very good indeed. But his army was handicapped by its undermanning, and chronically troubled by leadership problems, which were also the cause of the notorious indiscipline of Canadian aircrew. Even the Canadian official historian ventured the opinion that their army suffered from: