Outlaw in India

Authors: Philip Roy

Blood Brothers in Louisbourg

(2012)

Ghosts of the Pacific

(2011)

River Odyssey

(2010)

Journey to Atlantis

(2009)

Submarine Outlaw

(2008)

OUTLAW IN INDIA

Copyright © 2012 Philip Roy

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior

written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying

or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (the Canadian

Copyright Licensing Agency).

RONSDALE PRESS

3350 West 21st Avenue, Vancouver, B. C., Canada V6S 1G7

Typesetting: Julie Cochrane

Cover Art & Design: Nancy de Brouwer, Massive Graphic Design

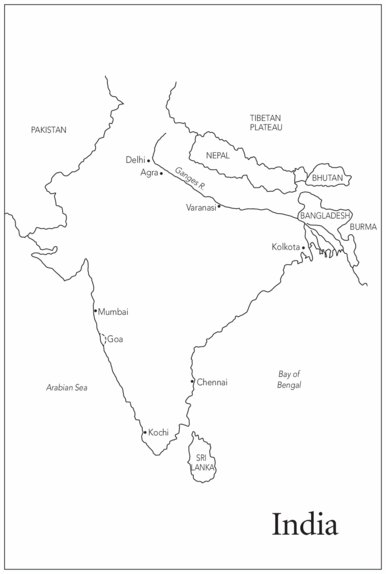

Map: Veronica Hatch

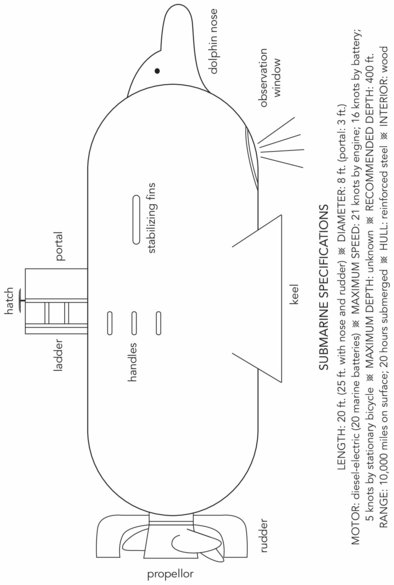

Submarine Sketch: Philip Roy & Julie Cochrane

Ronsdale Press

wishes to thank the following for

their support of its publishing program: the Canada Council for the Arts, the

Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the British Columbia Arts

Council and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Book

Publishing Tax Credit program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Roy, Philip, 1960–

Outlaw in India [electronic resource] / Philip Roy.

(Submarine outlaw series; vol. 5)

Electronic monograph.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-55380-178-8 (HTML)

I. Title. II. Series: Roy, Philip, 1960– . Submarine outlaw series (Online);

vol. 5.

PS8635. O91144O97 2012 jC813'.6 C2012-902661-1

At Ronsdale Press we are committed to protecting the environment. To this end

we are working with Canopy (formerly Markets Initiative) and printers to phase

out our use of paper produced from ancient forests. This book is one step

towards that goal.

for Angela

The people who enable me to continue writing this series are a growing number.

I would particularly like to thank the students I meet in schools, and their

dedicated teachers and librarians. They put a smile on everything. I must also

thank Ron and Veronica Hatch, and Deirdre and Julie, at Ronsdale; and Nancy De

Brouwer for her beautiful covers.

Family and friends who continually give me so much generous support are my

mother, Ellen; and Julia, Peter, Thomas and Lydia; my brother, Don; my buddy,

Chris, and Natasha and sweet Chiara; lovely Diana, Maria and Sammy; Zaan and

Nicholas; Hugh; Lauri; Dale and Jake (the intrepid). And a special thanks to

darling Leila, and Fritzi.

The heat of the sun comes from me,

and I send and withhold the rain.

I am life immortal and death; I am

what is and I am what is not.

â THE BHAGAVAD GITA

I WENT TO INDIA TO EXPLORE

. I wasn’t looking for anything in

particular, and I certainly wasn’t looking for trouble, I just wanted to

explore. Some of my discoveries were expected: the heat, ancient ruins,

dangerous snakes and millions of people. But there were also surprises—both good

and bad. And then there were a few things that seemed to find me, as if they had

been just waiting for me to show up.

And of course I did.

We were sitting in the water off Kochi, in the Arabian Sea. It was late

morning; the sun was high. I couldn’t see it through the periscope but it was

shining on the water. There were so

many vessels in the harbour it was hard to believe. My radar screen was

crowded with blinking lights. We had just come from the Pacific where we could

sail for days and days without seeing a single ship. Here it looked as though we

had just stumbled into a bee’s nest. There was a naval base here too, according

to my guide book, but I couldn’t see it. I wondered if the Indian navy had

submarines.

We had been at sea for weeks now and were anxious to get out and stretch our

legs and explore. If you stay cooped up too long you go crazy. But first we

needed to hide the sub. Seaweed was already out, hanging around with other

seagulls no doubt, and eating dead things. Hollie’s nose was twitching, sniffing

the smells of India that had seeped in when the hatch was open. He wanted

out.

“Just a bit longer, Hollie. We have to find a place to hide first.”

He looked at me and sighed. I steered into the harbour. Normally we would enter

a harbour like this only at night, but with so many vessels who would notice the

periscope of a small submarine? Who would be watching with sonar? It would be

like trying to find a pear in a barrel of apples—no one.

I had never seen so many ships in one harbour before. It was incredible. There

were freighters, tankers, barges, tugboats, Chinese junks, ferries, giant cruise

ships, small cruise ships, sailboats, fishing trawlers, fishing boats,

dories—everything but navy ships. Where were the navy ships?

The harbour was split into channels, like fingers of the sea,

and was a little confusing. The naval base must have been down one of those

channels. Through the periscope I caught a glimpse of the Chinese fishing nets

Kochi was famous for. They looked awesome. They were made of teak and bamboo

poles and the nets hung over the water like giant spider webs. They were

balanced so evenly it took only a few men to dip them into the sea and pull them

out with fish. It was an ancient fishing method but was still used today because

it worked so well.

I wanted to take pictures to show my grandfather, and then ask him why he

didn’t fish like that back in Newfoundland. My grandfather didn’t like trying

new things, which was why I liked showing him new things. I liked to challenge

him. He’d make a face like a prune and say something like, “Don’t fix it if it

isn’t broken.” But I wished he could see these nets because I knew they would

really interest him.

The oldest part of Kochi seemed a good place to hide. It was a seaport from the

days of wooden sailing ships. There were ancient warehouses hanging over the

water, and some were crooked and falling over. Broken piers stuck out of the

water like reeds in a river. Some were broken in half like broken teeth. This

part of the seaport had been abandoned a long time ago. Today all merchandise is

carried in metal containers on giant ships that are loaded and unloaded by

monstrous cranes in concrete terminals. When I turned the periscope around I

could see the cranes miles across the harbour. Old Kochi was a ghost town now—a

perfect place to hide a submarine.

I steered into a channel where the old warehouses were most

rundown, and cruised along on battery power until I saw one where I thought

maybe we could hide inside. The warehouse had a small boathouse at the very end

of it, like a shack on the side of a cottage, and there was just enough

clearance under water—about fifteen feet—for us to come inside. But I’d have to

be extremely careful to not bump the poles or the boathouse would tumble down

around us and maybe take the whole warehouse with it.

I was just about to steer in when I heard a beep on the radar. Another vessel

was coming into the channel. I turned the periscope around and saw a small

powered boat, possibly a coastguard vessel, coming in our direction. Shoot! I

hesitated. Should we stay or should we go? Did they know we were here? Either it

was a coincidence or they were investigating something they had picked up on

radar but couldn’t identify—us.

I shut off our radar so we would stop bouncing sound waves off them, which was

one way they would find us for sure if they had sophisticated listening

equipment, which they might have if they were the coastguard. I kept our sonar

on. It was unlikely such a small boat would have sonar. I pulled the periscope

down, let water into the tanks and submerged gently. We couldn’t submerge much;

the channel was only seventy-five feet deep. As we went down, I had to decide

whether to sit still and let them pass over us, or take off. The problem with

decisions like this is that there’s little time to think; you have to choose

quickly.

I put my hand on the battery switch and hesitated. The boat

approached. Were they slowing down? If they slowed down we would definitely take

off. No, they didn’t slow down. So we stayed. They went over us and kept on

going. Whew! Then, when they reached a bridge, about half a mile down the

channel, they turned around and started back. Rats! That wasn’t good. Now I had

that uneasy feeling in the pit of my stomach that said, “Get the heck out of

here!”

So I did. I cranked up the batteries all the way and motored to the end of the

channel as fast as the sub would go on electric power, turned to port and headed

out to sea. I watched the sonar screen to see if they would follow us. They did,

although they didn’t ride right above us, which told me that they knew we were

here but couldn’t locate us exactly. Maybe somebody had spotted us and reported

us. That had happened many times before in Newfoundland.

We followed the ocean floor down to two hundred feet as we motored out to sea.

It took awhile, and the coastguard boat followed us the whole way. Then I

levelled off and turned to starboard. The coastguard kept going straight. Yes!

We had lost them. They had never really known where we were; they had been just

guessing. But we couldn’t leave yet. We had to go back for Seaweed. I figured we

could sneak in at night, when we’d look no different on radar from any sailboat.

In the meantime, we could hide offshore by sailing directly beneath a slowly

passing freighter, so as to appear as one vessel on sonar and radar. It was a

great way to be invisible, though it

was noisy underneath a

ship’s engines. We had done it before.

It didn’t take long to find a freighter. I could tell what kind of ship it was

even without seeing it, by its shape on the sonar screen. Tankers were easiest

to identify because they were so big. Freighters had a sharper bow and flatter

stern, as a rule, although the bigger the ship, the broader the bow. Sometimes

older or smaller freighters had a pointed stern. This one was not very big and

was only cutting twelve knots, which was pretty easy to follow on battery power.

I figured we’d ride beneath her for ten miles or so, then find another freighter

going in the opposite direction and follow her back. When it turned dark, we’d

sneak into the harbour. Hollie took a deep breath and sighed.

“I’m sorry, Hollie. I’m trying. We really don’t want to get caught.”

We chased the small freighter for a few miles until we were right underneath

her, then we came up to just twenty feet beneath her keel. Her engines were

pretty loud. Suddenly she did something very strange. She turned sharply to

port. That was odd. Why would she do that? Was she trying to avoid something in

the water? Sonar didn’t reveal anything in her path. And then, she turned

again

, to starboard. What was going on? Did she know we were here? I

doubted it.

I was so curious I decided to drop behind, surface to periscope depth and take

a peek. I dropped back a few hundred feet, came up, raised the periscope and

looked through it. As my eyes adjusted to the light in the periscope, I got a

terrible

shock. The ship was battleship grey. She was carrying

guns. She wasn’t a freighter at all, she was a frigate, a navy frigate. We were

tailing a naval ship!

Although I knew we were in big trouble I didn’t quite grasp how bad it was

until some sailors on the stern shot something out of a small tube-like cannon

towards us. At first I thought it was just a flare—a warning—because it went

through the air in an arc like a flare. But there was no coloured streak.

Suddenly I realized what it was even before it hit the water. It was a depth

charge.

“Hollie!”

I grabbed him, hit the dive switch and ran for my hanging cot. I threw myself

on the bed with Hollie against my stomach just as the depth charge exploded. It

blew up beneath us. It was like getting kicked by a horse. My teeth bit into my

tongue. The blast hurt my ears, and there were strange sounds in the water

following it. We were diving now. I held onto Hollie tightly and covered his

ears. I wished I could have covered mine, because a second blast exploded right

outside the hull. And even though my eyes were shut, I saw red. It blasted my

ears so violently they started ringing and wouldn’t stop. It was like being

inside a thunder clap. The lights went out in the sub. The explosion knocked the

power out completely. Everything went dark. And we were going down.