Out of the Dawn Light

Read Out of the Dawn Light Online

Authors: Alys Clare

Recent Titles by Alys Clare

The Hawkenlye Series

FORTUNE LIKE THE MOON

ASHES OF THE ELEMENTS

THE TAVERN IN THE MORNING

THE ENCHANTER’S FOREST

THE PATHS OF THE AIR

*

*

THE JOYS OF MY LIFE

*

*

*

available from Severn House

OUT OF THE DAWN LIGHTavailable from Severn House

Alys Clare

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

First world edition published 2009

in Great Britain and in the USA by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD

of 9–15 High Street, Sutton, Surrey, England, SM1 1DF.

Copyright © 2009 by Alys Clare.

All rights reserved.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Clare, Alys

Out of the Dawn Light

1. Great Britain - History - William II, Rufus, 1087-1100 -

Fiction 2. East Anglia (England) - History - To 1500 -

Fiction 3. Detective and mystery stories

I. Title

823.9’2[F]

ISBN-13: 978-1-78010-087-6 (ePub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-6763-6 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84751-138-6 (trade paper)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by

Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland.

For my niece and goddaughter

Ellie Harris

with much love

ONE

T

he news of William the Conqueror’s death reached us when we were celebrating my sister’s wedding. My mother sniffed, drew in her lips and remarked that it was scarcely likely to affect us in our lonely corner of England, one ruthless Norman king undoubtedly being very much like another.

he news of William the Conqueror’s death reached us when we were celebrating my sister’s wedding. My mother sniffed, drew in her lips and remarked that it was scarcely likely to affect us in our lonely corner of England, one ruthless Norman king undoubtedly being very much like another.

My mother was wrong.

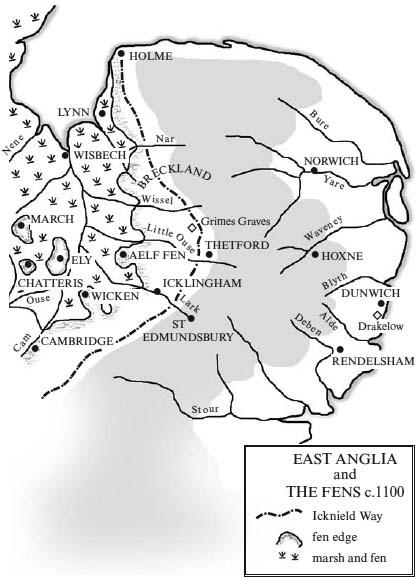

When I said we celebrated Goda’s wedding, what I meant was we were rejoicing because we would no longer have to share a home with her. For all of us – my mother, my father, my granny, my dreamy sister Elfritha who wants to be a nun, my brother Haward who has a terrible stammer but the kindest eyes in the Fens, my little brother Squeak the trickster, the baby in his cradle and me – this long-awaited day was just too good to let anything spoil it, even the news that the mighty King William, called the Conqueror, had died far away somewhere in France.

Squeak had prepared a sackful of tricks to play on the bride but for once my parents were in agreement and they strictly forbade him to perform any sort of a tease until Goda was safely wed. Squeak pleaded and wheedled – he is very good at both – and begged to be allowed just one little jest. The grass snake slipped into the foot of Goda’s bed, he suggested craftily, would be good because it would make sure she did not snore away half the morning and then get into a state because she did not have enough time to get herself ready. My mother heard him out impassively. Then she said, ‘Do the trick if you must. But if you do, you will stay here in the house while the rest of us enjoy ourselves and I shall pack you off to bed early in the lean-to. You will miss not only the food and the drink but also the storytelling.’

You could see Squeak weighing up the options. Teasing Goda has been the mainstay of his existence for most of his eight years and he was clearly loath to give up this one last chance to make her lose her fearsome temper. But Squeak loves stories even more than he loves playing tricks. With a fierce scowl, he grabbed the grass snake – already slithering enquiringly towards the cot where Goda still slept and snored – and stuffed it back in the sack.

I felt sorry for Squeak. But as my mother pointed out, nobody wanted Goda throwing a tantrum, holding her breath till her lips went blue and then announcing that she’d changed her mind and wasn’t going to get married after all. She had worked her way through this familiar sequence of events all too often in the preceding months. Now her wedding day had come and her family were united in their determination that nothing should prevent the marriage going ahead.

Goda has been a burden to me all the thirteen years of my life. Her only natural gift – a pair of breasts the size and shape of cabbages – never made up, in my mind, for her bad-tempered expression, her constant, grumbling self-pity, her laziness, her cruelty and her long tongue that could scold without ceasing for days on end. She has always disliked me. Once when we were playing in the water meadow she slipped and sat down in a cow-flop and I laughed and laughed, until she struggled up to display a large shit-brown stain on the back of her new tunic and boxed my ears so hard that, for all it was five years ago and more, I am still a little deaf in the left one.

Outsiders are wary of the Fens and tell fearsome tales of wicked spirits who infest our crude hovels, squeezing huge heads on skinny little necks through gaps in the walls, their fiery eyes glaring and their wide mouths full of horses’ teeth gnashing and gaping at us. They are sarcastic about the people of the Fens, saying that we are primitive, scarcely above the animals in our squalid, desolate marshy homeland. However, not being the backward simpletons they take us for, we know better than to permit inbreeding. We do not need the Church’s list of proscribed pairings. We know without being told that close relatives produce damaged offspring. So, several times a year when we take our animals to and from the summer pastures in the water meadows that flood from autumn to spring, we take our young adults along to the markets that draw folk from all around and usually one thing leads to another and betrothals are soon announced.

Goda was now eighteen and, maturing early as she did, she had been on the marriage market for four years and went to twelve markets before someone asked for her. Cerdic had come with his father and his uncle from their home down in Icklingham and one look at Goda was enough. She was wearing her gown low-cut that day and had somehow contrived to push up her breasts so that their upper curves all but spilt out. Cerdic drooled as he stared at her, open-mouthed and wide-eyed, and he set about winning her hand there and then. Poor man, he thought he had to fight off competition from others – no doubt Goda told him so – and in a way I hoped he never found out that every man but him might have appreciated Goda’s two unmistakable assets but soon discovered that they were vastly outweighed by everything else about her.

Well, it was too late now for him to turn back, or so we all fervently hoped. The morning went by in a flash – Goda reminded us constantly that this was her day and we all had to help her, so we were kept busy – and at last she was ready. There was no money for a new gown but she had restored last year’s, carefully unpicking the seams and turning it so that the faded outside was now inside and the outside was so bright that it almost looked new. She was clever with her needle and she had done a good job, although all the time she stitched my poor father had to endure her constant whining voice complaining that it was so unfair that nobody – by which she meant my father – had managed to stump up for her and here she was, reduced to turning a worn old gown, and wasn’t it just so sad for her? Then she would sniff and pretend to mop at her eyes. Father would usually get up from his place by the hearth and quietly leave the house.

Haward and Elfritha made a garland of flowers for Goda to wear in her freshly washed hair. Like me she has red hair, although hers is like carrots whereas mine, according to my father, is like new, untarnished copper. The garland was so pretty – Elfritha is very artistic – but, of course, it wasn’t good enough for Goda, who complained that the pink bindweed flowers clashed with her hair, and made Haward unwind every one.

At last we got her to the church door, where Cerdic was waiting. The priest prompted their vows and with our own ears we heard Goda state that she took Cerdic there present to be her husband. We all gave quiet but heartfelt sighs of relief.

When the vows and the praying were finished, we trooped back to our house and everyone milled about in the yard outside waiting to see what they were going to be offered by way of refreshment. Their feet made clouds of dust, only nobody seemed to mind. It was September, quite late in the month, but the weather was warm and sunny. Helped by my sister and my little brother, I had done my best to make the house look festive – it’s surprising what you can do with wild flowers, bunches of leaves and ears of dry corn – and there were several appreciative glances. At least, that’s what I told myself.

The one person whom I had really hoped to impress with my artistry, however, did not notice the decorations at all. He had found a place on one end of a straw bale and there he sat down, hunched his shoulders and then gave every appearance of someone trying to pretend they’re not there at all. Presently he was joined on his bale by a very old man whose spreading rump and widely splayed legs took up far more than his share. Serve you right! I said with silent venom to the youth beside him. Serve you right for sitting there looking as miserable as a wet summer and ignoring me all day!

The youth was called Sibert. He is quite a close neighbour of ours which, in a settlement as small as Aelf Fen, means that we see quite a lot of each other. He is fifteen, tall and slim, with fair hair that bleaches to white under the sun and light, bright eyes which sometimes look blue and sometimes green. I like him a lot and sometimes he likes me too.

Other books

The Ripple Effect by Rose, Elisabeth

Christmas Belles by Carroll, Susan

The Fullness of Quiet by Natasha Orme

Choices by Skyy

Survivor by Octavia E. Butler

A Magical Christmas by Heather Graham

The Sheik and the Slave by Italia, Nicola

The Last Watch by Sergei Lukyanenko

Murder on the Astral Plane (A Kate Jasper Mystery) by Girdner, Jaqueline

The Dark Enquiry by Deanna Raybourn