Out of the Blue

Authors: Sarah Ellis

Out of the Blue

Sarah Ellis

Groundwood Books

House of Anansi Press

Copyright © 1994 by Sarah Ellis

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author's rights.

“The Guide Marching Song” by Mary Chater is reproduced by permission of The Guide Association (UK).

This edition published in 2013 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Ellis, Sarah

Out of the blue

ISBN: 0-88899-215-7 (bound)Â Â ISBN 978-1-55498-471-8 (ebook)

I. Title.

PS8559.L5506 1994Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.54Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C94-931485-4

PZ7.E55Ou 1994

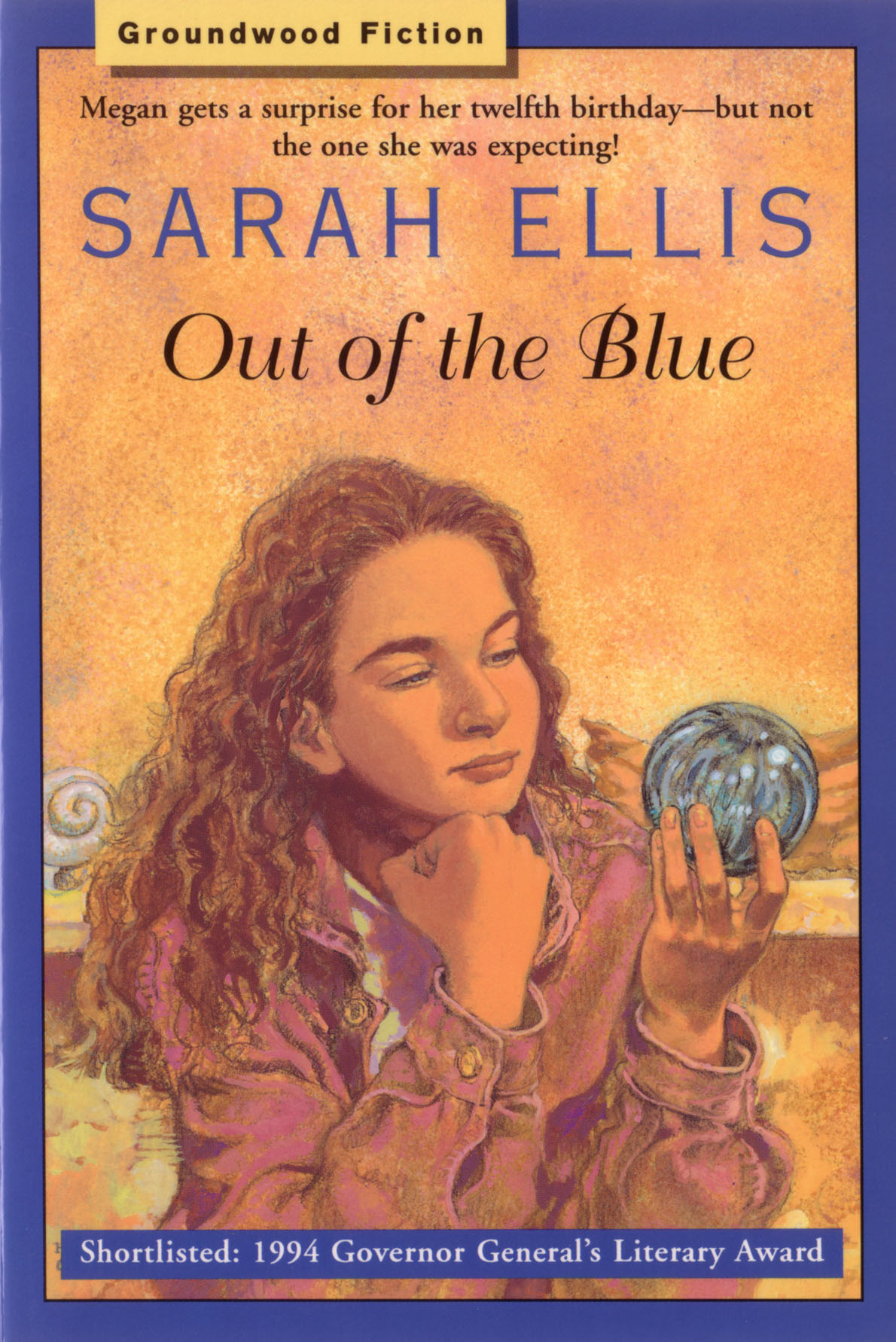

Cover illustration by Harvey Chan

Cover design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

For Claire Victoria, for later.

“THEN PRINCESS MAYONNAISE POINTED HER MAGIC

wand of power at the bad guys and turned them all into erasers. The end.”

Betsy somersaulted out of her beanbag chair and came over to the computer where Megan was typing. “Can you put âThe End' in those fat letters?”

Megan backspaced and pressed the

BOLD

key. “Okay. Anything else?”

Betsy pointed at the screen. “See where it says âerasers'?”

“Yup.”

“I need some room there so I can draw a picture, in case anyone thinks she changed those guys into shape erasers or neon erasers or sniff erasers. She didn't. She just changed them into dirty old pink erasers. All the same.”

“Right,” said Megan. “Now we can save.” The computer started to zip and bleep.

Betsy hung over the back of Megan's chair. “Did you like that story?”

“Yes, it's good.”

“Did you like it better or worse than âPrincess Mayonnaise and the Tooth Fairy'?”

Megan switched on the printer. “Um, I think I like it a bit better.”

“Did you like it better or worse than âPrincess Mayonnaise and Her Magic Wings'?”

Megan sighed. Giving a compliment to Betsy was like throwing a stick for Bumper. Once was never enough, and you always got tired of it before they did. “A bit better. Hey, while this is printing, do you want some juice? I'll go get it.”

“Sure.”

Megan stretched and went upstairs. As she crossed the hall to the kitchen she glanced through the open door into the living room. Mum and Dad were sitting on the couch, their backs to her. Mum's head was bent over a piece of paper.

In the kitchen the dishwasher was draining, doing its swamp monster impersonation,

glug, glug, swish.

Megan opened the refrigerator and took out a box of juice. The dishwasher clunked to a stop and Dad's voice fell into the silence, “Well, if you look at it that way,

everything

is a risk.”

Megan closed the refrigerator door quietly and grabbed two glasses from the cupboard. She stood at the living-room door and peeked in at Mum and Dad. Their heads were together now, outlined against the paper.

The printer stopped zipping and Megan went on down to the basement. Betsy was holding a long sheet of computer paper in the air. “Five pages! How many is that all together, Megan?”

“Thirty-eight plus five is forty-three.”

“Forty-three! That's way better than Kevin Bindings. He's only got twenty-seven. I've got the longest book in grade two. Is it really good, Megan?”

“It's a great book, Betsy.”

“Is it as good as

Mary Poppins

?

There was only one possible answer. “Yes. Now, you tear off the edges and do the drawing. Don't talk, okay? I've got homework.”

Megan turned off the computer and pulled out Betsy's “Mayonnaise” disk. She opened the drawer and filed it away, beside all Dad's stuff, disks marked “West Coast Foundation Proposal” and “Carswell Mining Annual Report.” Dad wrote things for businesses. Some days he put on a suit and went downtown to talk to people in offices. When he came home he usually pretended to hang himself with his tie, and then he would say, “Dynamic and innovative, dynamic and innovative, they all want to sound dynamic and innovative.” But most days he stayed home and worked on the computer, writing and making graphs and diagrams.

Megan closed the drawer and picked up her science notebook. Betsy lay on the floor and colored. She held the crayon tight in her fist and scrubbed at the paper. Megan stared at the bright splashes of color. Betsy didn't care about staying inside the lines. Megan pulled her attention back to putting the causes of acid rain into her own words.

Half an hour later Betsy pulled on her sleeve. She made strangling noises through tight-shut lips.

“Okay, okay, you can talk. What is it?”

Betsy pointed to the clock and whispered, “Look! Quarter to nine. They've forgotten to send me to bed.”

“You're right. Wonder why.” Megan listened carefully and heard the rise and fall of Mum talking upstairs. She realized that Mum and Dad had been talking all evening. It was like becoming aware of a clock ticking. Why wasn't Mum studying? Since she had started college in January she spent most evenings reading and making notes at the kitchen table.

“Let's just keep quiet,” said Betsy. “Maybe they won't remember until

midnight.”

The trouble was that after fifteen minutes of keeping quiet, they were both yawning, and midnight seemed a long time away. “Come on,” said Megan, pulling Betsy up out of the beanbag chair. “If we're too late, Dad won't read to us.”

They made their way upstairs and stood in the doorway of the living room. Mum and Dad were now at opposite ends of the couch, facing each other. Mum's voice had crying in it, “But, Jim, what if it doesn't work out? What if it's a big mis â

Megan coughed. Mum stopped midword, as though her voice had been snipped with scissors.

“Um, we're going to bed now.”

“What?” said Dad. “What time is it? Betsy! You're still up? Come on. We'll have to have a short chapter tonight.”

“There aren't any short chapters in Sherlock Holmes,” said Betsy with satisfaction, “I looked.”

Megan leaned over the back of the couch and kissed Mum. “Good night.”

Mum blinked and hugged Megan around the neck too hard.

“Aagh, you're strangling me.”

Later, as they were lying in bed listening to Dad read how Sherlock Holmes could tell all kinds of things about a man just by looking at his hat, the front door banged shut.

“What's that?” said Megan.

“Mum must be taking Bumper for a walk,” said Dad.

“But she already took him for a walk after dinner.”

“Megan!” Betsy bounced up and down on the bed. “Be quiet. It's getting to the part about the diamond.”

A few paragraphs later Betsy went from wide-awake to fast asleep, and Dad left Holmes parked in a pub. But Megan coasted along in half sleep for nearly an hour before the front door opened again and Bumper made his way upstairs. Three turns and a snuffle, and he settled down on the rug beside her bed. Everyone home.

The next morning Megan's hair decided to be stupid. By the time she fixed it with mist and the hair dryer she was the last person down to breakfast.

When she walked into the kitchen Betsy was in the middle of a temper tantrum. Mum was standing at the sink washing the porridge pot, ignoring the scene. Dad was being reasonable.

“Betsy, you have to change. You just put your elbow in your porridge bowl. You won't be able to wear your Brownie uniform today.”

“But I

want

to wear it.” Betsy's face was bright red.

Megan reached into the cupboard for the cereal.

Dad tried adding a suggestion to being reasonable. “Look. We can wash your uniform this evening, and you can wear it tomorrow.”

“I want to wear it

today.”

Where was the cereal? Megan tried the pantry cupboard.

Dad tried switching to humor. “Anyway, what would happen if you went to school with porridge on your elbow. People would want to come up and nibble it.”

Betsy gave a roar of rage and banged her mug on the table. Humor never worked with Betsy.

“Mum, where's the cereal?”

Mum didn't answer.

“Mum.”

Mum turned around and blinked. “What?”

“Where's the cereal?”

“The what?”

What was going on? Did Mum have an exam today or something? Megan spoke slowly and clearly. “The ce-re-al. Cornflakes. In a box.”

Betsy was now down on the kitchen floor, sobbing and hiccuping.

“Oh,” said Mum, “isn't it in the cupboard?”

“No! I looked there. Never mind. I'll have toast.”

Megan put two pieces of toast into the toaster and went to the refrigerator for peanut butter.There was the box of cereal, wedged in between the milk and the juice.

“Hey! Who put the cereal in the refrigerator?”

Betsy jumped up and her tears stopped, like a tap being turned off. “Let's see.”

“Oh,” said Mum. “I guess I put it there. Sorry.I'm not very with-it this morning.”

Dad walked over to the sink and kissed Mum on the neck. They stood there quietly for a few minutes, Dad's blond hair touching Mum's brown, Mum's hands floating quietly in the dishwater. Something was definitely up.

THE CEREAL DID NOT APPEAR

in the refrigerator again, but over the next few weeks Megan noticed a distinct weirdness in the air. And changes. “Minor points in themselves, Watson,” said Sherlock Holmes, “but as part of the broader picture I think we can deduce . . .”

Then, one Wednesday morning when Megan came down for breakfast, Mum was still in her housecoat.

“Aren't you going to anthropology?”

Mum's schedule was posted on the refrigerator and they all knew it by heart. And Wednesday was anthropology, first thing.

“No, I'm playing hooky today. Going to lunch with a friend.”

But Mum never skipped classes, not once in the three months she had been at school. Dad said she must be a professor's dream come true. And “lunch with a friend”? Mum didn't go out for lunch. Between classes she ate the sandwich that Dad packed for her. She didn't go out at all, except for bowling on Friday nights with Aunt Marie.

“I think I'll play hooky too,” said Betsy.

“No,” said Dad, “only one juvenile delinquent allowed per family.”

And then there was the discussion about summer holidays. Betsy arrived home from Brownies crying, holding a notice about summer camp. “It's in July! Finally I'm old enough for sleep-over camp and it's in July.”

Megan saw the problem. They always spent the whole month of July at the family cottage on the island. July was their month, and in August the cottage was for Aunt Marie and Uncle Howie and John. How could Betsy even think of missing a week on the island? But Brownie campâshe had been wanting to go ever since she found out that there were special camp badges.

“There's going to be cookouts, and sleeping under the stars one night, and everybody gets to take one stuffed animal....” Betsy's voice was rising and her fists were starting to clench. Bumper began to whimper

Moments to blast off, thought Megan. She was about to suggest a cookout when they were on the island but Dad interrupted. “No problem. It's going to work out just fine this year. We've decided to switch with Marie and Howie this summer and

we're

going to take August. So Brownie camp will be just fine. That was lucky.” He and Mum gave each other gooey smiles.

“Yea! I can go! Sign it, sign it!” Betsy danced around and then plunked the notice on the table.

Megan caught Mum's eye. “Why are we going in August this year?”

“Well, time for a change, we thought. We don't want to get into a rut.”

But Mum loved getting into a rut. She liked lists and priorities and things written on the calendar. She said that a solid schedule was the secret of a happy life.

Mum continued, “Besides, we might have something else on in July. We'll talk about it later.”

There was a period the size of a basketball at the end of her sentence. The answer that was no answer. What was with all this changing? It was like being on the island ferry when the sea was rough. You weren't sure where the deck was going to be on the next step. This was fun for a little while, but later it made you feel like throwing up. Dad called it “green around the gills.”

But the biggest change wasn't a schedule switch or an event. It wasn't a clue from which you could deduce something. It was just Mum. She kept humming all the time, and her eyes would well up with tears for no reason. It was like she had taken off the fast let's-get-things-organized coat that she usually wore, and under it was this soft, slow person. The same person who took care of Bumper when he was a puppy. The same person who would sometimes sing soppy songs like “Whispering while you cuddle near me” with Dad. But now this person was around all the time.

One night, while Dad was reading the last chapter of

The Hound of the Baskervilles,

Mum appeared and said they all had to come to the bathroom to look at the moon. The bathroom was filled with silvery light, and the moon through the window was huge and full.

“Good night for a tramp across the moors,” said Dad, who was still in a Sherlock Holmes mood.

“Is it a full moon everywhere at the same time?” asked Betsy. “Like in Africa and Australia. Does everybody get the full moon on the same night?”

“Yes,” said Dad. And then he paused. “At least I think so.”

“They don't get summer and winter at the same time,” said Betsy. “How come they get the full moon at the same time?”

“Hang on,” said Dad. He laid out a bar of soap a rubber dinosaur, and the dental floss on the back of the toilet. “Now, if this is the earth and this is the moon . . .”

But Mum just kept staring up. “Yes, it

is

the same. Anyone looking up in the sky right now sees this full moon. Everyone.”

And the tears ran down her face. She hugged Megan around the head. Suddenly the bathroom seemed very small to Megan. There was certainly no space for questions. There was hardly enough space to breathe.