Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (3 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

In these ways, then, Palestine was like any other region in the Ottoman Empire, and its history over the nineteenth century assumed familiar Ottoman patterns. At the same time, several factors made the Palestinian experience different from that of other Ottoman provinces and regions. As the site of worldwide religious devotion, Palestine had become an object of heavy international scrutiny and intervention by the turn of the century. Missionaries, pilgrims, and diplomats made their way to the region, many of them staying and putting down roots. With changes to the Ottoman land laws in the 1850s, several groups of Christian religious settlers—Germans, Americans, and Swedes—arrived to purchase land, establish agricultural colonies, and settle among the local population. Most significantly in numerical as well as lasting political terms, Jewish migration to Palestine, which had been a small but steady stream throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule, picked up heavily in the second half of the nineteenth century. Religious European Jews arriving to live and die in the Holy Land, North African Jews fleeing French colonialism, and Yemenite Jews with messianic visions were soon joined by a new kind of Jewish immigrant: the politically motivated settlers of the nascent European Zionist movement. The tensions that arose in Palestine in the last years of the Ottoman Empire between Zionists and their opponents—Arab Muslims and Christians, to be sure, but also fellow Jews and other Ottomans—were reflective of both local and empire-wide problems.

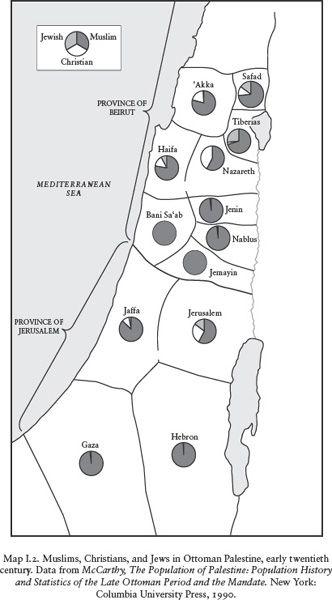

Like the rest of the Ottoman Empire, then, the region of Palestine was also the product of complex demographic and social mixing. By the turn of the twentieth century, Palestine had a population of around 700,000 to 750,000, the great majority of which, around 84 percent, was Muslim Arab. Approximately 72,000 Arab Christians (11 percent of the total population) lived in the two administrative provinces that made up Palestine, concentrated in the cities and towns of Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, and Nazareth, and in the semiurban townlets and villages surrounding them. Finally, there were around 30,000 Ottoman Jews in the region (5 percent of the Ottoman population), as well as up to 30,000 foreign Jews living there temporarily or permanently. Jews lived primarily in the four cities

holy to Judaism (Jerusalem, Hebron, Safad, and Tiberias), as well as in the coastal cities of Jaffa and Haifa; in addition, up to 10,000 European Jewish immigrants lived in the almost four dozen Zionist agricultural colonies newly established since 1878.

32

The two most important cities in southern Palestine, Jerusalem and Jaffa, were also the most heterogeneous: Ottoman Jerusalem was 41 percent Jewish, 34 percent Muslim, and 25 percent Christian—even without accounting for the steady stream of noncitizen pilgrims, travelers, businessmen, and migrants who came to the city that was sacred to the three religions.

33

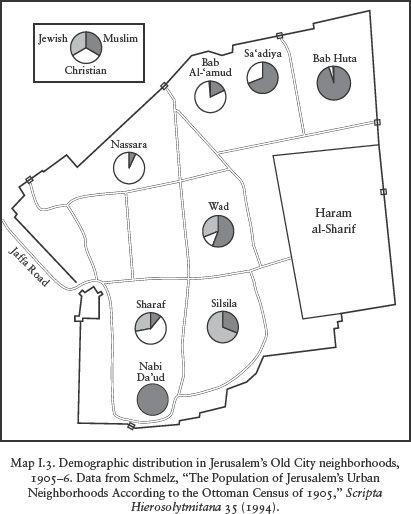

According to the 1905 Ottoman census records, of the eight

neighborhoods within the Old City walls of Jerusalem, only three were religiously homogeneous (defined as at least 80 percent concentration of one religious group), while the remaining five had a substantial mixing (20–45 percent) of members of two or all three religious groups. Not surprisingly, the two most homogeneous neighborhoods included Bab Huta, a 95 percent Muslim neighborhood that bordered the eastern entrance to the Haram al-Sharif–Dome of the Rock Mosque complex, and al-Nassara, a 93 percent Christian neighborhood surrounding the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate.

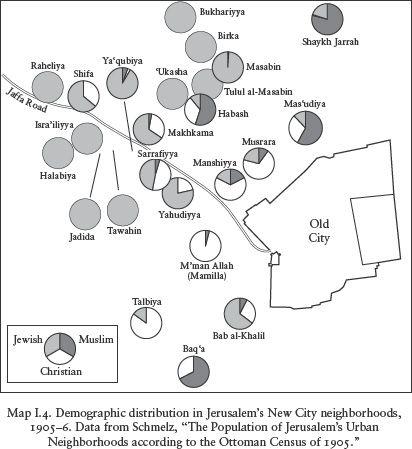

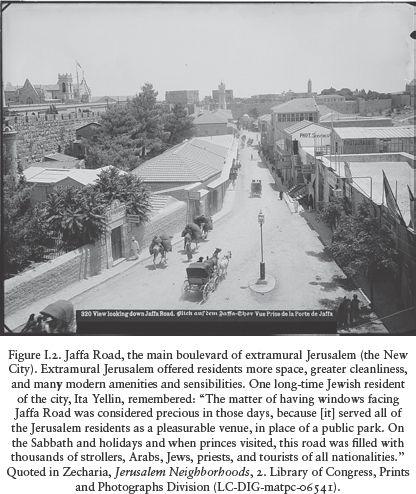

In contrast to this residential intermixing in the “Old City,” the extramural “New City” featured religious separation from the outset, in

many cases as a desired and declared goal. Beginning in the 1850s, Jewish philanthropic societies and Christian religious institutions purchased land and established neighborhoods for their co-religionists' exclusive use, and wealthy Muslim notables established family compounds outside the city walls. As a result, almost half of the extramural neighborhoods were religiously homogenous.

34

Many of these were self-contained, self- supporting neighborhoods, which further limited the residents' contacts with outsiders: the Ashkenazi Jewish neighborhood Me'ah She'arim, for example, had its own synagogues, ritual bath, religious schools, cisterns, grocery store, and guest house.

35

In Jaffa the situation was even more marked.

36

As a result of this spatial mixing, there developed in Jerusalem a local set of norms about communal, ethnic, and religious boundaries and borders. Many memoirs from this period speak of deep ties between Old City Muslim, Christian, and Jewish families and neighbors across religious lines—sharing a courtyard, visiting each other on religious holidays, engaging in a business partnership, or benefiting from a long-term patron-client relationship. Muslim girls learned Judeo-Spanish from their Sephardi Jewish neighbors; Christian and Jewish musicians performed at Muslim weddings and holidays; and all three shared beliefs and traditions about the evil eye, droughts, and visiting the tombs of local saints.

37

At the same time, religious, economic, and political rivalry appeared from time to time, and the practical aspects of “living together” could be a source of tension. Christians and Jews in particular had fraught intergroup relationships, especially around religious holidays and religious holy sites. Easter-Passover was a particularly dangerous time as Christian Arabs sang anti-Jewish songs on the streets of the city and blood libels accusing Jews of using Christian children's blood for ritual purposes resurfaced periodically.

38

Jews and Muslims, on the whole, did not share the same religious tensions marring their relationships, but economic and political factors played a role in conflicts between these two groups.

39

As a result, the Jewish rabbis in Jerusalem sought to limit the impact of “living together” by the system of azakah

azakah

, whereby one Jew would hold the title to sublet courtyard apartments in a Muslim-owned building. The title holder then was the only one who had to exchange money with a non-Jew, and he also had the discretion of determining to whom the apartments would be rented.

40

Another factor contributing to the complex picture of intercommunal relations, these memoirs also suggest, was that intraconfessional boundaries could occasionally be as strong as, or at times even stronger than, interconfessional ones. Many memoirs argued that “native” Sephardi and Maghrebi Jews shared cultural, spatial, and everyday practices with their Muslim neighbors that sharply differentiated them from “newcomer” Ashkenazi Jewish co-religionists. In Jerusalem as in many other towns throughout the Ottoman Empire, Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews spoke different mother tongues, went to different synagogues and schools, lived in different neighborhoods, and usually married within their own ethnic group; they also had different relationships with the Ottoman government and their neighbors.

41

This separation was so complete that in 1867 Ashkenazi Jews in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman government, through the intercession of local Muslim notables, to recognize them as a separate sect

(madhhab)

, thereby allowing them autonomy from Sephardi institutional and political hegemony.

42

Likewise, the Christian community in Palestine was fragmented into sixteen different religious denominations, many of which had their own religious, educational, and legal institutions. Rivalries among the Christian denominations with respect to religious rites and sacred privileges were legendary, and many an Ottoman governor had to intervene to calm tempers and break up fistfights in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The daughter of one Ottoman governor who served in Jerusalem at the beginning of the twentieth century recalled that her father had to mediate an argument over unruly choir boys drowning out the other denominations, as well as one about the status of a cushion that one patriarch made for the gatekeeper of the church (they argued that one denomination could not give the cushion to the gatekeeper, as it would privilege that group).

43