Other Women (22 page)

Authors: Fiona McDonald

Maria’s wealth allowed her a support team who could look after children and household duties; thus she was able to take up her art practice again. Georgiana, on the other hand, although certainly not poor, could not afford such a luxury and had given up all thought of her own artistic dreams when she married. Burne-Jones, wrapped up in his gorgeous new model who was beautiful and clever, could not help feeling tied down by his older and home-obsessed wife. However, it was Georgiana who would stick by him through thick and thin, nurse him when he was ill and keep his finances in check. Without that steady person in the background he, like many other artists and creators, would not have functioned at all. What is more, when she did find an incriminating letter in the pocket of her husband’s jacket, Georgiana did not confront him with it but remained as passive as ever.

Maria returned Burne-Jones’s passion, even though he was getting on for 40 and she was only in her mid-20s. He drew caricatures of himself as a gawky scarecrow of a fellow, constantly wondering what she saw in him. While the affair was at its height Burne-Jones’s work flourished. His output was both prolific and of high quality, but it was not sustainable and nor was the pressure of guilt at betraying his wife.

Finally Burne-Jones tried to break off the affair. Ruskin has left documentation of his friend’s attempts and also how they failed. Burne-Jones wanted both his beautiful, rich, fascinating mistress and his loyal, efficient wife, mother of his beloved children. Maria had hatched a plan in which the two of them would run off to a Greek island and live there happily ever after. Burne-Jones, initially excited at the prospect of leaving his ordinary life behind, was tempted for a fleeting moment, before reality brought him to his senses. He could not do that to his family, nor his friends, patrons or himself. It was a fantasy and he knew it; Maria did not.

In 1869 Maria ordered her lover to walk with her in Lord Holland’s Lane, where she told him that she was taking enough laudanum to kill herself. They walked, talked, argued, pleaded and tried to reason with each other. By the time they had reached the bridge over Regent’s Canal, Maria was in such a state that she tried to throw herself into the water. Burne-Jones grappled with her and they rolled around on the ground. Two policemen turned up, separated the pair, restraining Burne-Jones while trying to get to the bottom of the matter. Luckily Maria’s cousin and former lover, probably jealous for her attention, turned up and took charge of Maria, helping her to walk away. It seemed he had known something was up and deliberately followed the pair.

Burne-Jones arrived home in a dreadful state, his nerves were shot to pieces and he was shivering with shock and cold. Georgiana put him straight to bed, no questions asked. William Morris came to the rescue claiming that Burne-Jones could do well to have a little trip to Rome, an artists’ inspirational journey. It would get his friend away from the dramatic Maria and give him time to recover. They got as far as Dover and had to go back as Burne-Jones was too ill to travel. For some days after his return home Georgiana pretended he was still away, believing his shattered mind and body needed quiet rest. She even lied to friends about his whereabouts so that nothing would intrude on the healing process.

While his health did revive somewhat he was left in a delicate state. Also, Warrington Taylor, the manager of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co., told both Burne-Jones and Rossetti that their romantic affairs would ruin the firm’s reputation if they continued. Burne-Jones, suitably chastened, was filled with guilt. He had been unfaithful to his wife, ruined the life of his beautiful mistress and was possibly damaging his business partners.

Still, none of this stopped Burne-Jones’s affair with Maria from continuing, albeit at a less tumultuous level. They saw each other regularly, went out together, stayed in together and fought with each other. Until 1872, that is, when Maria suddenly went to Paris. There is conjecture that she had lined up a new lover in France and as her previous one was not going to sacrifice everything for her she could now afford to toss him aside. Even though things settled down a bit after she left, a correspondence continued between them for years afterwards, and in 1874, during a trip by Burne-Jones to Italy, there is evidence that they met up again and continued where they had left off two years before.

In 1875 a new muse entered Burne-Jones’s world. Frances Grahame, the daughter of one of his friends, had grown into a lovely young woman. She was not 20 and Burne-Jones was 40. Although he sent her letters full of his undying love, his grand passion and his need for her, Frances, although flattered and kind was not interested in starting an affair with him. Over the next few years Burne-Jones would continue to press his suit but to no avail. Frances, having married John Horner and started a family, always remained kind and loving to Burne-Jones but was never able to reciprocate the type of love he wanted. Perhaps he would not have known what to do with it if she had. As we have seen, when he had succumbed to the beautiful Maria he had become immensely unsettled and unhappy.

While renewing his pursuit of Frances, Burne-Jones was also declaring his love for another woman, a friend of Frances’s, Helen Gaskell. She was 39 to his 58. Helen was another woman in distress, very unhappily married to a man who may well have beaten her. Their meetings had to be kept secret, although it doesn’t seem as though the affair had a sexual element to it.

These last two attempts at romantic unions with beautiful women, whom Burne-Jones liked to paint, came to nothing. Before his death he asked all the recipients of his love letters to destroy them as he did not want anything to remain to incriminate him and bring his widow embarrassment. However, most of them did not. Georgiana wrote a biography of her husband but was careful to gloss over areas that were painful to her and to his memory.

Burne-Jones and Georgiana were married for thirty-six years. In all that time she only played the muse for a brief time, but in reality she was the stability behind him that let him indulge in the emotional rides that gave him the inspiration to paint.

Mistresses in the

Twentieth Century

LORENCE

D

UGDALE AND

T

HOMAS

H

ARDY

When Florence Dugdale wrote to Thomas Hardy in 1905 asking if she could meet him, he had already been married to Emma for thirty-five years. They had a convivial marriage although they had stopped sharing a bedroom since 1899. They were companionable but were steadily growing further apart. Hardy had been tempted to have an affair from as early as 1889 when he fell in love with the married Rosamund Tomson, but she was only interested in friendship. Then there was Florence Henniker but she too was only wanting a platonic relationship, flattered by Hardy’s attentions but nothing more.

Then Florence Dugdale’s letter came out of the blue, telling the writer how much she loved his work and she really wanted to meet him. Although Hardy received fan mail he had never received this kind of request before and he invited her to come to his house, Max Gate. By chance or design Emma was not there. Lunch was very enjoyable and Hardy invited Florence to come again.

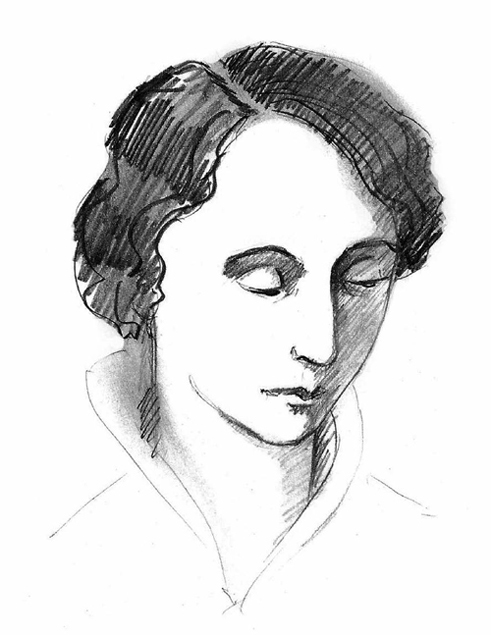

Florence Dugdale

Hardy was in need of a muse and he thought he might just have found her in pretty, young and intelligent Florence Dugdale. For her part, Florence enjoyed having someone to admire, or at least she pretended she did. What her motives were it is difficult to tell. She was an aspiring writer and maybe wanted a helping hand in getting work published, or she may have been genuinely a keen fan.

Florence was one of five daughters of the headmaster of a Church of England School at Enfield, north London, and a staunch supporter of the Conservative Party. She became a pupil-teacher at her father’s school when she was 15 until it became too much for her and she took a position as a lady’s companion in 1906. What she really wanted was to be a writer. One of the things that make Florence’s motives for Hardy’s friendship questionable is the way she has distorted the truth about certain aspects of how they met and what her true employment was. For a start, she didn’t want to publicly admit she was a paid companion, instead she told people she was just visiting friends, staying with them for a while. Then there were some curious anomalies in her tale about meeting Hardy. She never admitted she had written to him as a complete stranger and invited herself to his house. She gave a couple of different accounts for this. One was that she had met the Hardys while out walking with a friend, they got chatting and she was invited back to their house; another version has Florence Henniker introducing her to the Hardys as a couple. The latter story cannot be true because Florence Dugdale did not become acquainted with Florence Henniker until well after she had established her friendship with Hardy.

The old lady to whom Florence had been hired as companion finally had to go into a nursing home. Her husband, Sir Thornley Stoker, had enjoyed having Florence about the place. He had given her a typewriter when he discovered she wanted to be a writer and then on his wife’s death gave her a ring. Florence used her typewriter a lot, teaching herself to touch type. Finding out that Florence could type gave Hardy an excuse to see more of her. She would type for him, something that she later used as a step up the ladder by stating she had been his secretary. Hardy also got her to undertake research for his work. In return he sent letters of introduction to newspapers and publishers recommending her work and Florence began to carve out a career for herself as a writer.

Hardy fell in love with Florence; he took her on holidays, wrote her letters and praised her writing (when in fact, according to opinion, it was really quite ordinary). One thing he did not intend, though, was to leave his wife Emma. It was years before Emma and Florence met, and their eventual meeting had nothing to do with Hardy. Emma was to give a talk at the Lyceum Club of which Florence was a member. On hearing of this Florence asked Hardy if she should introduce herself. Hardy was very encouraging.

Instead of being a rival for her husband’s affection, Emma found Florence as admiring of her as she was of Hardy. Florence was good at flattery. She liked to make people feel good, although she had her own reasons for doing so, usually to do with her ambition.

What transpired was another triangle: Hardy, Emma and Florence. Both Emma and Thomas Hardy loved Florence, both wanted her attention and sometimes the result was disastrous, such as the Christmas of 1910 when Florence spent it with the Hardys at Max Gate. Hardy told Emma he wanted to take Florence to meet his family. Emma was very angry and told him that they were sure to try their hardest to make Florence hate her. Emma stormed out of the room and Florence swore to herself she would never spend a Christmas with the pair again.

Then at the end of November 1912 Emma died suddenly after complaining of feeling unwell. She had gone to bed one evening, agreed to see the doctor but refused to let him actually examine her. She died the following morning from heart failure.

Hardy was not thought to be able to manage on his own. Although he had several domestic staff he needed a housekeeper. There were two contenders for the position: Florence, of course, and Emma’s niece Lilian. Katie, Hardy’s sister, had stepped in for the interim. Lilian probably wanted to escape living with her mother and saw her uncle’s situation as perfect; she’d be head of the household, a woman with influence and authority, she’d also be able to entertain Hardy’s interesting guests, all in a highly respectable situation. However, Katie and Florence couldn’t stand Lilian; she was domineering and snobbish, especially to Florence. Lilian was out to make trouble; not only did she want the position for herself but she wanted to know what Florence had to do with her uncle, she spread rumours about Florence that began to cause problems for Hardy.

Emma’s death had been a shock to Hardy. He had probably taken her for granted then when she suddenly wasn’t there any more he began a period of profound reminiscing. These thoughts and memories were set down as a series of poems, which became some of his greatest work. To escape into the past was a glorious way of avoiding his present problems, which involved who was going to do what at Max Gate. Hardy wanted to please everyone and himself; he wanted to avoid scandal but did not want to lose Florence, who was still very much the object of his passion. Yet at the same time all he wanted to do was think about his life with Emma. Eventually he asked Florence to marry him, thinking that by making her mistress of the house all problems would be sorted. Yet it wasn’t going to work that easily. Lilian had been poisoning the staff against Florence and if she continued in the house there would always be an undermining of Florence’s authority.