Oscar Wilde and the Nest of Vipers (27 page)

Read Oscar Wilde and the Nest of Vipers Online

Authors: Gyles Brandreth

Tags: #Historical Mystery, #Victorian

I believe Oscar was the only one of us who did not laugh. He murmured to me, ‘That was poorly done. I feel a fellow poet’s pain.’

As the theatre manager retreated to break the news to poor McGonagall, the prince, helping himself to a second sandwich, sought to set the scene for the seance.

‘Gentlemen, if you would kindly form a circle please – a circle around the professor. To see into your souls Professor Onofroff will need to look into your eyes. Isn’t that correct, Professor?’

Onofroff smiled and, as his thick lips parted, his mouth revealed an array of gold and silver teeth. ‘Yes, Majesty,’ he whispered.

‘Oscar,’ called out the prince. ‘You’re in charge. Get the troops into a circle. Eddy, you come stand by me.’

‘Who is to be included, sir?’ asked Oscar.

‘Everyone.’

‘Including staff, sir?’

‘Everyone – except Mademoiselle Dvorak. I think we can excuse the lady. She is too young for secrets.’

‘What is this with secrets?’ enquired Dvorak anxiously.

‘Patience, Maestro,’ said the prince cheerily. ‘Let Mr Wilde put you in your place – all will be revealed. You have nothing to fear.’

Once each man was in his place, the prince called for hush. ‘We are in the professor’s hands now. Gentlemen, please do as he asks you.’

‘What’s all this in aid of, sir?’ enquired Prince Albert Victor.

‘Clearing the air,’ said his father. ‘Now concentrate on the professor.’

‘Gentlemen,’ whispered the professor, ‘thank you for your kind attention.’

As he spoke, he stood in the centre of the circle, revolving very slowly, looking into each face in turn.

‘His Majesty is correct. I am here to help clear the air – and perhaps help clear the conscience, too. Look into my eyes,

gentlemen, as I look into yours. Look directly into my eyes – look into my soul as I look into yours. Speak to me as I look at you – speak to me, not with words, but with thoughts. Share your thoughts with me. Let me read your minds.’

‘If you can read my mind, Professor,’ said Prince Eddy, ‘you’ll know I’m deuced hungry. Let’s get on with this.’

‘I can read minds, Your Majesty. I can read yours.’

‘You’re a professor, Professor,’ said Lord Yarborough pleasantly. ‘Are you offering us any scientific proof?’

‘Who has a pen or pencil?’ asked the professor.

‘I do,’ said Oscar, producing a small silver pencil and a visiting card from his waistcoat pocket.

‘Kindly write down a word for me, Mr Wilde – whatever word is in your mind.’

Oscar scribbled briefly on his card.

The professor said at once, ‘The word is “love”, is it not, Mr Wilde?’

‘It is,’ said Oscar.

I looked over his shoulder. It was.

‘I want to play this game,’ said the Prince of Wales, breaking from the circle and coming over to claim Oscar’s pencil and card. ‘What’s the word I am writing, Professor? What’s in my mind? This’ll test you.’

Onofroff hesitated. ‘It does, Majesty,’ he said, closing his eyes to concentrate. ‘It is not a word I know. Or if it is, I think it is a card game. You are thinking of “Loo”, of “Loo-loo”. Is that possible? Does that make sense?’

The prince held out his card for general inspection. On it HRH had written the name ‘LULU’ in capital letters.

He laughed. ‘That’s proof enough for me, Professor – and I’m patron of the Royal Society. On with the experiment.’

‘Thank you, Majesty. Let us all concentrate once more,

gentlemen. In complete silence. And as I look into your eyes, let me read your mind, let me learn your secret.’

Dvorak was on the far side of the room to me, but I could hear the composer’s teeth grinding.

‘We all have secrets,’ continued the professor. ‘And I sense dark secrets in this room. Everywhere I turn, I see a secret. Look into my eyes, gentlemen, and release your secrets. I will share your burden and your secrets will be safe with me.’

As the professor turned carefully from one pair of eyes to the next, speaking of sensing dark secrets in the room, it seemed to me that the room itself begin to darken: the gas lamps flickered and burned lower than before. Beyond the faint grinding of Dvorak’s teeth and the slow, heavy breathing of the Prince of Wales, there was nothing to be heard but the steady hiss of the lamps.

At least two minutes of this profound stillness must have passed before the professor spoke again. When he did so, for the first time within my hearing his voice was raised above a whisper. He spoke, in fact, with a sudden, chilling authority.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘enough. I know the truth.’

And as he said it, from within the vestibule, a terrifying scream was heard – long, piercing, pitiable.

‘My daughter!’ cried Dvorak, breaking from the circle and running across the ante-room to the vestibule.

Every one of us turned to follow him. Oscar and I pushed past the prince’s page and reached the scene at once.

Dvorak’s daughter was standing, unharmed. She flung her arms around her father and buried her face in his chest.

‘My God,’ cried Dvorak, his face contorted, ‘look at that.’

The composer stood by the door that opened on to the tiny square room built into the corner of the vestibule, containing the water closet. There, thrown back against the wall, was the

bloodied body of Mademoiselle Louisa Lavallois – the Prince of Wales’s Lulu. Her bodice had been ripped open, her perfect titties scratched, torn and cut across. Her neck was twisted grotesquely to one side and punctured with two gaping, bloody holes. Her eyes were wide open, but she was undoubtedly dead.

A Duty to the Truth

51

From the Daily Chronicle, final edition, Wednesday, 19 March 1890

H

ORROR IN

L

EICESTER

S

QUARE

The mutilated body of a young female dancer was discovered in a dark alley off Leicester Square in London’s West End late last night. The body is believed to be that of Miss Louisa Lavallois, twenty-six,

première danseuse

with Les Ballets Fantastiques, a French troupe currently appearing at the Empire Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square.

The body was discovered shortly before midnight by the Leicester Square lamplighter, William Higgins, as he went about his business. According to Mr Higgins, the body had been secreted behind dustbins beneath an unlit lamp in Derby Alley, immediately adjacent to one of the side entrances to the Empire Theatre on the north side of Leicester Square. On discovering the partly clothed cadaver, Mr Higgins immediately alerted the police. Senior officers from Bow Street police station and the Central Office at Scotland Yard were on the scene soon afterwards.

The horrific nature of the attack upon the young dancer is reminiscent of the notorious ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders that have caused so much alarm in London in recent years. Since the assault on Emma Elizabeth Smith in Whitechapel in April 1888, eleven young women have been mutilated and murdered in London in similar circumstances. Most recently, on 10 September last, the torso of an unknown female was found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel.

Inspector Walter Andrews of Scotland Yard, one of the officers investigating the ‘Jack the Ripper’ killings, attended the scene of the crime in Leicester Square last night and said afterwards: ‘We are ruling nothing out at this stage, but at first sighting this does not look like the work of the man known as Jack the Ripper. Throat cutting and abdominal mutilation have been a common factor in the Ripper murders, all of which have taken place in and around the Whitechapel area of East London. In this case the physical attacks on the deceased, though similar, are distinctly different, and Leicester Square is a long way from Whitechapel.’

Top of the bill at the Empire last night were Dan Leno and the Scottish Bard, the Great McGonagall. The house was full for the performance and the audience is said to have included certain very distinguished persons.

Tonight’s performance will commence at 7.15 p.m. as usual, but will not include Les Ballets Fantastiques as a mark of respect for the deceased.

52

From the journal of Arthur Conan Doyle

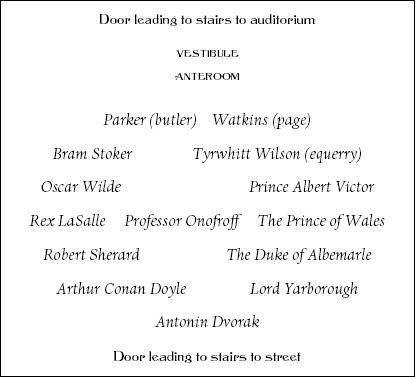

Yarborough and I examined the body together. We were left in peace to do so. The royal party departed at once – we agreed it was best. They took Onofroff with them and left, without ceremony, via the stairs that led directly from the ante-room to the street. Oscar and his young men took charge of Dvorak and his daughter, giving them brandy and sandwiches from the sideboard. Parker, the Duke of Albemarle’s butler (a better man than I had realised), kept

cave

at the door to the vestibule, while the duke helped us lay out the dead girl’s body on the floor.