Oracle Bones (68 page)

Authors: Peter Hessler

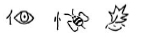

Imagine that three simple pictures represent the English words “leaf,” “bee,” and “eye”:

Now, reorganize the three pictographs:

Speak the words quickly: “

Eye-bee-leaf

; I believe.” That takes care of two abstractions: the first-person noun and the verb of faith. If you want, you can add simple markers that will allow a reader to distinguish “eye” from “I” and “believe” from “bee-leaf”:

In such a system, the writer listens for connections between words—homonyms, near-homonyms, rhymes—and then expands the vocabulary of the original pictographs. The key element is sound: a symbol represents a spoken sound rather than a picture. And that’s when you have writing, strictly defined: the graphic depiction of speech.

Nobody has found direct evidence of these early stages—it’s not the kind of thing that would have been recorded—but experts believe that’s roughly how it happened. The earliest known writing in East Asia is already a fully functioning system by the time it appears on the oracle bones. The Shang characters are not pictographs, although many of them contain links to that earlier stage. The Shang word for “eye” is written:

This kind of writing system is called logographic. Each character represents one spoken syllable, and syllables having the same sound but different meanings—homonyms—are represented by different characters. For example, the modern Chinese (“great”) is written differently from

(“great”) is written differently from (“wilt”) and

(“wilt”) and (“false”), despite the fact that all three are pronounced exactly the same:

(“false”), despite the fact that all three are pronounced exactly the same:

wei

. The other known ancient scripts, Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics, also first appear on the archaeological record at the logographic stage. (Sumerian is the earliest known script, appearing roughly 1,700 years before the oracle bone inscriptions.) Most scholars believe that Chinese developed independently, although Victor H. Mair and a few others theorize that the Shang had contact with the writing of the Near East.

None of these early scripts is easy. In a logographic system, thousands of symbols must be memorized, and a reader often can’t pronounce an unfamil

iar word without looking at a dictionary. During the second millennium

B

.

C

., Semitic tribes in the Near East converted Egyptian hieroglyphics into the first alphabet. An alphabet allows a single syllable to be broken into even smaller parts, which gives far greater flexibility than a logographic system. With an alphabet, it’s possible to distinguish homonyms in subtle ways (“see” and “sea”) instead of writing completely different characters. Unfamiliar words can be sounded out, and an alphabet shifts more easily between different languages and even dialects. For example, one can listen to somebody from the American south say “I believe,” and then, using the Latin alphabet, describe his pronunciation of each syllable: “Ah bleeve.”

A logographic system can’t capture that level of nuance. And an alphabet requires the memorization of only two or three dozen symbols, instead of thousands of characters. That’s why, in the Near East and the Mediterranean, the old systems didn’t survive. There are no direct descendants of Sumerian cuneiform, and Egyptian hieroglyphics remain with us only indirectly, as the inspiration for the first alphabet.

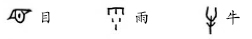

But the Chinese still write in characters. In the history of human civilization, written Chinese is unique: a logographic script whose fundamental structural principles haven’t changed in more than three thousand years. Even the characters themselves are remarkably timeless. Today, when a Chinese writes

mu

, or “eye,”

yu

, or “rain,”

niu

, or “ox,” the modern words stand beside the Shang characters like close relatives:

NOBODY KNOWS WHY

the writing system remained so stable. The spoken language of ancient China was chiefly monosyllabic (most words consisted of only one syllable), and it was uninflected (no changing endings for plurals or verb tenses). Some linguists note that these qualities made Chinese naturally suited to a logographic system. The Japanese, whose spoken tongue is highly inflected, originally used only Chinese characters but then converted them into a syllabary, a simpler writing system that makes it easier to handle changing word endings.

Other scholars point to cultural reasons. Ancient Chinese thought was deeply conservative—the ancestor worship, the instinct for regularity, the resistance to change, the way that Confucianism idealizes the past—and such

values naturally would make people less likely to modify their writing system. But that’s a chicken-and-egg theory, and the fundamental issue isn’t why the writing system remained stable. The key is how this written stability shaped the Chinese world.

For most of China’s history, official writing used classical Chinese. By the time this language was standardized during the Han dynasty, more than two thousand years ago, it existed only in written form. People wrote in classical Chinese, but their day-to-day speech was different. Over time, as the spoken languages evolved, and the empire expanded, encompassing new regions and new tongues, classical Chinese remained the same. A citizen of the Ming dynasty spoke differently from a citizen of the Han—they were divided by more than ten centuries—but they both wrote in classical Chinese. The native language of a Fujianese was different from that of a Beijing resident, but if they both became literate, they could understand each other’s writing. Classical Chinese connected people across space and time.

It would have been harder to maintain such literary stability with an alphabet. In Europe, Latin was the written language of educated people for centuries, but they always had the necessary tool to shift to the vernacular: the alphabet made it linguistically easy. (Of course, cultural and social reasons delayed the transition.) In China, there was also some vernacular writing, but it was limited. Vernacular writing is less likely to develop in a logographic system, which simply can’t shift as easily as an alphabet among different languages and dialects.

But Chinese characters had other benefits. They provided a powerful element of unity to an empire that, from another perspective, was a mishmash of ethnic groups and languages. Writing created a remarkable sense of historical continuity: an unending narrative that smoothed over the chaos of the past. The characters were also beautiful. Calligraphy became a fundamental Chinese art, much more important than it was in the West. Words appeared everywhere: on vases, on paintings, on doorways. Early foreign visitors to China often remarked the way characters decorated everyday objects such as chopsticks or bowls. At Chinese temples, prayers were traditionally written rather than spoken; fortune-tellers often made their predictions by counting the strokes of a written name. In the nineteenth century, social organizations were devoted to collecting scraps of paper that had been dignified by writing; they couldn’t bear to see them tossed away like trash. Communities erected special furnaces to give these words a proper cremation.