Operation Mercury (17 page)

Authors: John Sadler

This refusal was in spite of the fact a platoon sized patrol from the 21st had reported the Germans had a strong lodgement on Andrew's southern flank at Vlakherontissa. Yet nobody moved. Both battalions concentrated on holding their own positions while reporting back to brigade that all was quiet in their respective sectors.

Brigadier Hargest confirmed that nothing further would be required of them âunless position very serious'.

18

In fact the position was quickly becoming very serious indeed and Andrew's

19

messages to brigade were anything but relaxed. He reported that he'd lost contact with his forward companies, dug in on the western flank of Hill 107, that his positions were being bombed relentlessly and that the German strength was growing with a corresponding increase in their deployment of heavier weapons.

These messages became increasingly desperate as the day progressed. Andrew reported that his HQ company had been penetrated, that the left flank of his battalion was giving way. At 5.00 p.m. he bluntly demanded to know when he might expect reinforcement; when would the 23rd appear?

Hargest did not immediately respond but when he did it was to advise that the 23rd was already fully committed â this was entirely fallacious. Having seen off Scherber's attack the battalion had scarcely fired a shot. Inevitably Brigadier Hargest's conduct has been much criticised. However, such criticism must always be considered in the light of the prevailing fears of an invasion from the sea. Paratroop landings, in this context, were no more than either a diversion or an overture. Hargest was certainly a very brave man, an eyewitness at Thermopylae remembered the General:

⦠standing in the centre of a group among some olive trees and saying, with tears running down his cheeks, âI have in the past had to retreat when I have been driven out of a position, but this is the first time I've had to retreat without a fight'. My second picture of him is at Sidi Azziz on the morning of 27th November 1941. We had been attacked by a force of German tanks, artillery and motorised infantry and the guns of E Troop, 5th Field regiment had been knocked out one by one. Before that the anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns had been knocked out and we were obviously losing the battle ⦠Hargest stood a little to the right of the line of fire of our 25 pounders, and in front of them, wearing his red cap and with his hands in the pocket of his coat. He did not take cover at any time. We were firing over open sights at tanks, and when the last of our guns was out of action and our ammunition truck caught fire, Hargest put his hands up and walked towards the German tanks.

20

Whatever the reason for this extraordinary reply, Andrew felt that all he could now do was to mount a local counter-attack with whatever he had in hand. North of the beleaguered Hill 107 the Colonel had stationed his pair of Matildas which were now to be thrown into the attack in an attempt to drive off the Germans on the periphery of the airstrip and retake the bridge over the Tavronitis. One of the strategic failings surrounding the Battle for Crete, as some commentators have pointed out, was the dispersal of the available armour. Using tanks in penny packets to support local infantry attacks had been a weakness in the Battle for France â it remained so here on Crete.

The actual usefulness of heavy tanks such as the Matilda for operations in such harsh and hostile terrain was also subsequently scrutinised. The After Battle Report concluded that the light tanks were very effective in dealing with enemy machine guns and nests of snipers.

Safe from small-arms fire they could hose the ground with their own machine guns then charge home as light cavalry, crushing or overrunning the foe; any survivors could be dealt with on a hand to hand basis. If these tactics sound exceedingly brutal, they were certainly effective. Whether the heavier infantry tanks could perform as well in this close support role was far less certain.

Andrew dispatched Peter Butler, formerly of C Company, as a runner in mid-afternoon, to establish contact with Captain Johnston. On his way, hastened by threatening bursts from MG 34s, he blundered into a well-concealed tank. The commander advised him that he was still awaiting orders before engaging. Butler spent over an hour crouched with his former comrades in their exposed positions before being sent back with a situation report. Returning around five, he was in time to witness the counter-attack, spearheaded by the Matildas.

The line of attack had been worked out between Johnston and the tank crews the day before and, as the Captain records:

The tanks left their concealed position at 5.15 and moved west past company headquarters along the road towards the river in single file about thirty yards apart ... the second tank turned about before reaching the bridge and came back past company headquarters on the Maleme road.

21

This inspiring beginning proved anti-climactic for, as Butler records, the second tank soon came lumbering back. Apparently the ammunition for the machine gun was of the wrong calibre and the traverse mechanism for the turret was jammed. The first of the tanks, however, managed to descend into the dry river bed from the road and move forward under the span of the iron bridge. The ground was alive with Germans who were badly rattled by its appearance.

Student later admitted that his men, already dazed by their heavy losses, were reduced to something akin to panic by the arrival of British armour, which was impervious to small-arms fire. Gericke, amongst those crouched in the rocks, confessed that this new development caused ripples of fear amongst his tired men. However, the threat proved more apparent than real. The broken ground afforded plenty of cover and the tank was not, in fact, able to inflict many casualties.

Matters quickly degenerated for the British. This tank soon stalled and, with its turret also jammed, the crew baled out and were captured. The lead platoon from C Company, following in the wake of the metal monster, was caught in a most unfavourable position, assailed from all sides. The survivors were forced into an ignominious and costly retreat, leaving a scattering of dead and wounded. Of the attacking sections only three men came back unwounded.

22

A gallant gunner who had, with his comrades, volunteered to fight as a foot soldier when their gun had been knocked out earlier, was amongst those who failed to return. The whole sorry business was over in half an hour and with nothing to show for the loss.

It would be easy to find fault with Andrew for launching a small, local counter-attack which could only bring very limited resources to bear against an enemy now well dug in and over very difficult ground. This would, however, be unfair. The Colonel was acutely aware of how exposed his forward companies were and of the need to relieve them from the relentless pressure now building up from west of the Tavronitis. For Andrew the failure to establish defences in this vulnerable sector was now bearing bitter fruit. His oft repeated pleas for additional support had gone unheard; it is difficult to see what other choices were available to him.

With his attack stalled and fearing the two forward companies had been overrun, Andrew spoke again to Hargest and warned he might have to withdraw from Hill 107. The Brigadier's reply was âIf you must, you must'.

23

In fact both Johnson and Campbell were hanging on. A and B companies had barely engaged, Andrew nonetheless proposed to fall back to B Company Ridge, a spur that lay below Hill 107 and was, in fact, very much in its shadow.

Despite the desperate fighting in Andrew's sector and the clear implications of abandoning Hill 107, Hargest does not seem to have felt the need to inspect his forward battalion, preferring to remain at Brigade HQ. The question therefore arises as to whether he felt that he had to conserve his strength to repel a second, seaborne attack on his sector. If so, and it may well be the case, then ULTRA had, in fact, worked for the Germans rather than the Allies by causing them to âlook the wrong way'!

Having thought again, however, Hargest decided to detach two companies â one from 23rd Battalion and a company of Maoris from the 28th, despite the fact they were a good eight miles distant. Andrew, being apprised of this then, for whatever reason, continued with his phased withdrawal from the hilltop and from the eastern perimeter of the airfield. By 9.00 p.m. the relief company from the 23rd was to hand and Andrew sent them off toward the rise of Hill 107 from which his own men had just withdrawn.

The Maoris were held up, became lost and ended up in a satisfying but pointless firefight with a group of parachutists barricaded in houses by the coast road. The obstacle was cleared and prisoners taken but Andrew, physically and emotionally exhausted, had decided to withdraw his whole force toward 21st and 23rd Battalions, abandoning Hill 107 again and take position on B Company ridge. With this was lost the infinitely greater prize of the airfield itself and the situation lurched from deadlock toward disaster.

Suffering from heavy casualties and having been profligate with their ammunition, the Germans were scarcely placed to renew the attack. C and D companies, despite losses, were by no means beaten; âstill full of fight' though their ammunition was lower than their spirit.

24

Campbell, who was expecting his position to be utilised as a jumping off for a fresh counter-attack, at first refused to believe that he had been abandoned. Only when he and his CSM confirmed, from personal reconnaissance, that Battalion HQ was an empty shell, did the full realisation sink in.

25

The order to split into three detachments and filter southward through the tangle of hills must have been a galling one, to give up a position so bravely held and break off from a fight that seemed to be winnable. Johnson, even more exposed on the seaward side of the aerodrome, hung on till first light then, unable to establish contact with anyone from battalion, led his men back toward the 21st. The exhausted Germans simply let them go but it was a tragic end to so determined a stand.

An opportunity, not one to be repeated, had now been lost and the debate over who was to blame has raged ever since. Freyberg, as C.-in-C., had always regarded Maleme as the prime Axis target. Captured orders have since confirmed this, so the degree of laissez-faire which obtained at Brigade and Divisional HQ seems hard to comprehend. One explanation, which has been offered, is that Hargest was in the habit of delegating visits to the forward positions to his immediate subordinates. There is, of course, in theory, nothing wrong with this. The brigadier should, in a conventional battle, remain so placed that he can respond to events across the board.

This, however, was not a normal battle. It was not a conflict of attrition or even of mass manoeuvre â it was a fight for a single key objective, which would unlock not just the sector but the entire Allied position. It has been suggested that:

Had Brigadier Hargest gone to his forward Battalions himself instead of sending his Brigade Major (Captain Dawson) there might have been a different story to tell. Surely he would have vetoed the withdrawal of 22nd Battalion from the airfield. Surely he would have launched a counter-attack, and his presence would have inspired the troops at a time when inspiration was needed.

26

1. British, Australian and New Zealand troops disembark at Suda Bay, Crete.

(Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Photo DA-01611)

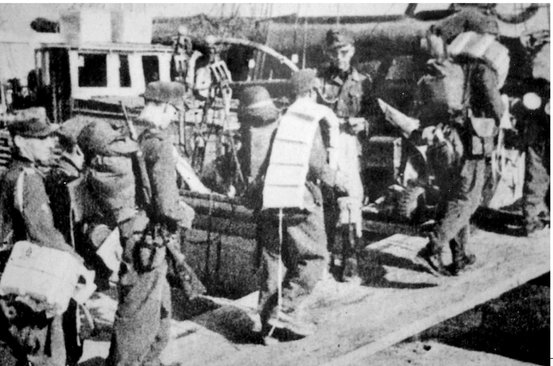

2. Alpine troops boarding Greek vessels.

(Courtesy of the Naval Museum, Chania)

3. General Thomas Blamey, in command of Australian forces in the Middle East.

(Courtesy of the Naval Museum, Chania)