One Was Stubbron (5 page)

“Shut up,” said Carpdyke, “I'm busy.” And to himself, “When he gets chased all over the post with that, we'll try pink

beta rays

and maybe a left-handed Geiger counter. Thenâ”

There was a stuttering snarl out in the hangar and heavy ground vibrations as a big motor warmed. The chief scowled. He looked at his assignment sheets and let off a couple of regulation growls.

“No flights due off for a week. What's wrong with them monkeys?” He went to the office door and stood there, a little blinded by the pink daylight. He saw a Number Thirty Starguide being dollied out by a tractor for a takeoff. It wasn't the space admiral's barge, but a routine mission cruiser. And the peculiar thing about it was, no lab crew standing by.

When they had the Starguide into position for its launch one lone figure came shuffling out, climbed the ladder and popped into the hatch. The tractor detached itself and the tower waved all clear.

There was something reminiscently all wrong about the man who had entered that ship and the chief was almost ready to turn away when it struck him.

“Pettigrew!” He started to run into the field and then realized his complete lack of authority. He dashed back.

Carpdyke was still absorbed.

“Sir!” said the chief. “That ensign got a ship! He's about to take off!”

Carpdyke almost said “I'm busy,” and came alert and up instead. “Who?”

“Pettigrew got a ship. There!”

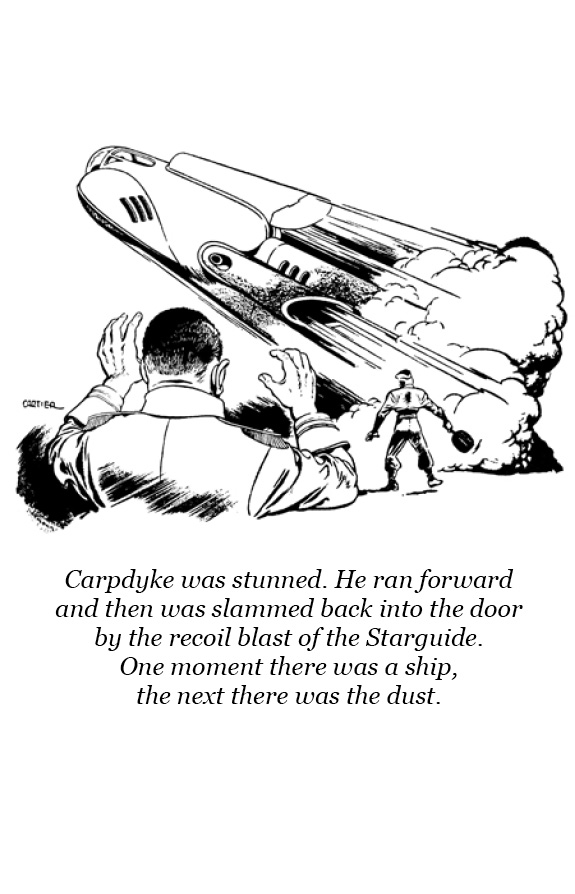

Carpdyke was stunned. He ran forward and then was slammed back into the door by the recoil blast of the Starguide. One moment there was a ship, the next there was the dust. Pettigrew was gone.

“You sure that was Pettigrew?” cried Carpdyke.

“I seen him.”

Carpdyke breasted the flying clouds of dirt which lingered and got himself to Flight Operation.

He slammed inside. “What's going on? Who was in that ship?”

“Ensign Pettigrew,” said the warrant dispatcher.

“What?” cried Carpdyke. “Where is Lieutenant Morgan?”

“Sick bay,” said the warrant dispatcher. He had been scared for a moment but now he knew he was in the right. He was an old Navy man. An order was an order and he had the copy right there.

“Why did you let that man get away?”

“Sir,” said the warrant, “I seen your order not ten minutes back. We was to lend every assistance to Ensign Pettigrew. Well, we did!”

Carpdyke was keeping upright by holding the edge of the signal rack. A million dollars' worth of spacecraft, the life of a new officerâ “But he ⦠but that was justâ” He caught hold of himself. “That order was intended to be seen by Morgan. The man was new.”

“I got the duty,” said the warrant doggedly, “and I obeyed it.”

Carpdyke went away from there with a complete panorama of a twelve-man court-martial board staring him unsympathetically in the eye. What had he sent that fool after? Rudey rays. Knowing less than nothing about the fiery character of luminous masses, an ensign would burn himself to bacon crispness the first one he ran through. No ensign, no ship, no further career for Carpdyke.

He had no choice but to declare himself guilty. He went into the outer office of the admiral's suite and looked sadly at the adjutant. “Is he in?”

“Sure, butâ”

Carpdyke went wearily by and breasted the barricades.

Banning was rather fat, somewhat crotchety, and had a most wary eye upon his future. He had managed to live twenty-one years with the Navy without sullying his record and if he could keep one more clean he would be pleasantly selected up by his friends to some post as galactic commander with the rank of sixteen stars. Today he was musing upon his happy future, making thoughtful steeples with his fingers and watching his favorite cat dozing in the daylight which poured in.

“Sir,” said Carpdyke, remembering suddenly that he had forgotten his jacket and cap, “a new man, Pettigrew, just reported. An ensign. He was awful green and I sent him out with a funny order and Morgan is in sick bay today and his warrant obeyed the order and now Pettigrew and a million dollars' worth of Number Thirty Starguide are on their way someplace to get fried. I am turning in my resignation and will hold myselfâ”

Banning's eyes went round as he attempted to digest these facts. Then he ordered a repeat and when it had been carefully told four or five times with details, he suddenly understood that sixteen stars might very well eclipse if such things were found to have happened on his base.

“Order up the cruisers! Send out ten destroyers! Man the warning net!” bawled Banning. And then he grabbed his cap and sprinted for the radio room.

Carpdyke relayed the orders and within ten minutes, where peacefulness had reigned, great waves of motors began to beat and the ground quaked under the impact of emergency takeoff.

The men were not quite clear on what they were to do or where they were to go. And it took Banning several minutes on the shortwave to convince four or five irate commanders, who objected to leaving so fast, that they were not about to repulse a rebel attack.

Meanwhile a small, dark radioman was having no luck with Pettigrew. “Sir,” he said to Banning, “he can't have any channels switched on. I've tried them all. And probably he's outraced even the ion beams by this time. I don't thinkâ”

“Don't think!” cried Banning. “Don't ever think! Stop that ship!”

But nobody stopped that ship. For five standard days Banning's guard fleet raked and combed the surrounding space and then, because they had left without proper provisions, began to return one by one, each with negative news.

Carpdyke, miserable but not under arrest yet because Banning could not stop worrying long enough to think up the proper charges, wandered around the hangars. He received very little sympathy. Hardly anyone on the project had escaped Carpdyke's somewhat heavy wit and, combined with this, all crews present had gone without liberty or relief for a week. The project was very grim. The brig was full of people who hadn't saluted properly or had demonstrated negligence in the vicinity of Space Admiral Banning. Things were confused.

At least three times a day Banning picked up his pencil to send intelligence of this harebrained accident to the department and each time was stopped by his vision of those sixteen stars. He could court-martial Carpdyke, but then it would come out that Carpdyke was notorious and that Banning, being of the haze school himself, had never put a

full astern

on the practice. Banning was confused.

Ten days went by with no word of Pettigrew and out of complete weariness the project began to settle into an uncertain sort of routine. The chaplain left the bridge table long enough to inquire whether or not he should read an absentee burial for the young officer and was told off accordingly. Scout ships returning with routine data were ignored and immediately fell under the same gloom which was downing everyone else.

Nobody spoke to Carpdyke.

When the admiral spoke to anybody they got rayburns.

The post publicity officer began to write up experimental releases about another brave young martyr of science and the master-at-arms inventoried the scanty baggage of Pettigrew. People began to look worn.

And then, at four o'clock of a September day, a Number Thirty Starguide, rather singed around the edges and coughing from burned-out brakes, came to rest before Hangar Six and out popped a very secondhand version of Bigby Owen Pettigrew.

People stopped right where they were and stared.

“Hello,” said Pettigrew.

But people just stared.

Admiral Banning had been soon told and was coming up puffing and scarlet. Carpdyke slithered out of his office and tried to seem as if he wasn't present.

“Hello, Mr. Carpdyke,” said Pettigrew.

“Young man!” said Banning. “Where have you been?”

“Are you Admiral Banning?” asked Pettigrew.

“Answer me!”

“Well, I guess I been all around, mostly. I scouted about three nebulas and almost lost the whole shooting match in the last one, what with the emissions and all. And I got pretty shaken up with the currents and reversed fields andâ”

“What was the idea taking off that way?” cried Banning.

“Well, Mr. Carpdyke, he told me to go out and get a quart of rudey rays and Iâ”

“A quart!” cried Banning.

“Yes, sir. Seemed kind of funny to me, too. But he said these rudey rays was the germs of new universes so Iâ”

“Rudey rays!”

“No, sir, I never heard of them either, Admiral. But orders is orders, so I went outâ”

“You young fool! You might have been killed! You might have lost that ship!”

“Admiral,” said Pettigrew, “that's just the way it seemed to me, too. But when he said how powerful these rudey rays was, why, I recollected when I was flying the Mailâ”

“What mail? I thought you were a UIT man!” said Banning.

“Oh, sure, I am, sir. But five or six years before that I was flying the Empire Mail. Then when I found that new fuel you're using, they give me a scholarship to UIT which was mighty nice because back in Texas I never got much formal learning. And after I'd done some work on star clusters they said was new, why, I wanted to get back to flying again, so I figured this was the place to be. I ain't much of a hand about the Navyâ”

This startling dissertation was abruptly punctured by the arrival of a cruiser which slammed down smartly enough to knock out a couple of windowpanes.

From it stepped a splendid young captain who approached the waiting group and saluted the admiral.

“Captain Congreve, sir, reporting to relieve the exec. Iâ Oh, hello, Pettigrew!”

There was so much warmth in Congreve's voice that Banning was startled.

“You know this man?” cried Banning.

“I certainly do. And I can recommend him to you heartily,” said Congreve. “Picked him myself after Universal Admiral Collingsby swore him in. He invented the billion-light-year fuel capsule. You've heard of him, haven't you? Well, you must have: I see you've been on a mission already.”

“Yes, sir,” said Pettigrew. “I was sent off to get a quart of rudey rays.”

“A ⦠a what?”

“And I got 'em,” said Pettigrew, pulling a flat jar from his sagging jacket. “Had quite a time and near got sizzled but they're tame enough. I saturated sponge iron with them and the filings are all here. Kind of a funny way to carry the stuff but I guess you Navy guys know what you are doing.”

“Rudey rays?” said Banning.

“Thousand-year half-life,” said Pettigrew, “and completely harmless. Good brake fuel. Won't destroy grass. By golly, Mr. Carpdyke, it was awful smart of you to figure these things out. They ain't in any catalogue and I sure didn't know they existed.”

Technicians passed the flask from hand to hand gingerly. The counters on their wrists sang power innocuous to man and sang it loud.

“That's all I could get this trip. Nebula One, right slam bang center of the Universe,” said Pettigrew. “Well, there she is. If you'll excuse me, I don't look much like a naval officer and I better change my clothes.”

They stared after him as he went to quarters, the master-at-arms trotting after to break out his impounded gear.

There was a queer dazed look about Carpdyke. But Banning was not dazed. He fired some fast, smart questions at the technicians and when they had examined the fuel in the lab, they gave him some pretty positive answers.

Banning stood looking at Carpdyke, then, but not seeing him. Banning was seeing sixteen stars blazing on the side of a flagship and maybe not a whole year away after all.

“Sir,” stammered Carpdyke, “I'm sorry. It came out all right but I know I jeopardized equipment. He looked so young and green and I figured it would take a lot of roasting to make him an officer and I never intended he would actually get off the baseâ”

Captain Congreve looked mirthfully at Carpdyke, for the captain understood the situation now.

“Commander,” said Congreve, “I wouldn't let this throw you. You see, the reason Collingsby swore that man in as an ensign and not as a lieutenant was because Pettigrew had something of a reputation in the Empire Mail.”

“A reputation?” said Carpdyke.

“Yes,” said Congreve, gently. “A reputation as a practical joker, Commander, and he'd been warned about you.”

“A pract ⦠a practicalâ” began Carpdyke, feeling most ungodly faint at what this would do to his reputation everywhere.

“Carpdyke,” beamed Banning, clapping him on the shoulder in a most friendly, sixteen-star-blinded way, “supposing we all go over to the club and let you buy us a drink?”

240,000

Miles Straight Up

CHAPTER ONE

Left at the Post

T

HE

party

was wild. The night was gay. And the “Angel” was very, very drunk.

But who wouldn't have got drunk on such an occasion? The Angel was about

to head man's first attempt to conquer space and within a few short hours he would

be boring space to the moon, 240,000 miles straight up.

He had tried to stay sober but this, being without precedent in the

Angel's career, was entirely too great a strain. “Don't dare take another grink â¦

well ⦠jush one more â¦

hic

!”

The Angel was First Lieutenant Cannon Gray of the United States Army Air

Forces, Engineers. He was five feet two inches tall and he had golden curly hair and

a face like a choir boy. Old ladies thought him wonderful and beautiful. His

superiors, from the moment he had entered

West Point

, had

found him just about the wickedest, hard-drinkingest, go-to-hell splinter of steel

they'd ever tried to forge.

The Army, with a taste of opposites, called him Angel from the first,

called it to his face, loved him and was hilarious over his escapades.

This was probably the first time in history that Angel had attempted to

stay sober. But it was a wonderful party they were giving in his honor (two floors

of the

Waldorf

plus

the ballroom) and people kept insisting that he

wouldn't get another chance at a drink for months and maybe never and everyone was

so pleasant that good resolutions were very hard to holdâespecially for a dashing

young officer who had never tried to make any before.

The occasion was gala and his hand was sore from being pumped by

brass

hats

and newsmen and senators. For at zero four zero eight of the

dawning, First Lieutenant Cannon Gray, USA, was taking off for the moon.

It was in all the papers.

Several times Colonel Anthony, a veritable old maid of a flight surgeon,

had tried to pry his charge loose and steer him to bed and, while Angel seemed

willing and looked

blue eyed

and agreeable, he always vanished

before the hall was reached. Really, it was not Angel's fault.

No less than nineteen frail, charming and truly startling young ladies,

all professing undying passion and future faithfulness, had turned up one after the

other and it was something of a task making each one unaware of the other eighteen

and confirming in her belief in his lasting fidelity.

Such strains should not be placed upon young men about to fly 240,000 miles straight up. And it takes hours to say a proper

goodbye. And it takes more hours to be respectful to brass. And it takes time, time,

time to drink up all the toasts shoved at one. All in all it was a very exhausting

evening.

Not until zero one zero six did Colonel Anthony manage to catch the

collapsing Angel in such a way as to keep him. Wrapped in the massive grip of

Colonel Anthony, Angel said, “Candrin four oh eigh â¦

snore

!”

The golden head dropped on the Colonel's eagle and Angel slept.

Cruelly, it was no time at all before somebody was slapping Angel awake

again, standing him on his feet, getting him into a uniform, wrapping him up in

furs, weighing him down with equipment and generally tangling up a dark, dismal and

thoroughly confused morning.

Angel was aware of a howling headache. Small scarlet fiends,

especially commissioned by the Prince of Darkness for the purpose, played a gay

chorus with red-hot hammers just behind Angel's eyes. He was missing between his

chin and his knees and his feet wandered off on various courses.

A

flight major and two sergeants,

undeniably capped with horns, danced in high anxiety around him and managed to touch

him in all the places that hurt.

He was in horrible condition and no mistake.

And the watch on his wrist gleamed as hugely as a steeple clock and

said, “Zero three fifty-one,” in an unnecessarily loud voice.

The corridor was at least half the distance to Mars and Angel kept

hitting the walls. The casual chairs with which he collided all apologized

profusely.

A potted palm fell on him and then became a general who, with idiotic

pomposity said, “Fine morning, fine morning, Lieutenant. You look fit. Fit, sir. No

clouds and a splendid full moon.”

He felt the call, one which generals too old for command can never

resist, to give a young officer the benefit of a wealth of experience but,

fortunately, his aide swiftly interposed.

The aide was brilliant with the usual aide's enthusiasm for paper glory

and distaste for generals. Angel knew him well. The aide, in Angel's day at the

Point, had been an upperclassman, a noted grind, a shuddery bore and the darling of

his seniors. He didn't look any better to Angel this morning.

“Beg pardon, sir,” said the aide sidewise to the general, “but we've

just time to brief him as we ride down. Here, this way Lieutenant.” And, abetted by

the usherlike habit peculiar to the breed of aides, he got Angel into the car.

“Now,” said the aide to Angel, who was hard put to stifle his groans and

shivers at the unearthly hour, “you have been thoroughly briefed. But there must be

a quick resumé unless you think you are thoroughly cognizant of your duties.”

Angel would have answered but the sound came out as a groan.

“Very well,” said the aide, just as though his were the really important

job and Angel was just a sort of paperweight, very needful to aides but not at all

important. “The staff is terribly interested in your surveys.

“You will confine yourself wholly to this one task. It has been thought

wisest to entrust a topographer with this first mission because, after all, that's

the way things are done. We've insufficient reconnaissance to send up a main

body.”

Angel would have added that he was a guinea pig. They didn't even know

if he could really get to the moon. But aides talk like that and lieutenants somehow

let them.

“As soon as you have completed a survey of an elementary sort you will

televise your maps, then send a complete set in a pilot rocket and return if you are

able. But you are not to risk bringing the maps back personally.”

They were little enough sure he'd ever get there, much less get

back.

“You will phone all data back to us. Our tests show that the wave can

travel much further than that. Anything you may think important, beyond maps and

perhaps geology, you are permitted to note and report.

“Under no circumstances are you to attempt to change any control

settings in your ship. Everything is all prenavigated and proper setting will be

phoned to you for your return.

“All instructions are here in this packet.”

Angel shoved the brown envelope into his jacket and felt twinges of pain

as he did so.

“My boy,” said the general, getting a word in there somehow, “this is a

glorious occasion. You have been chosen for your courage and loyalty and it is a

great honor. A great honor, my boy. You will, I am sure, be a credit to your

country.”

Angel didn't mean it to be a groan but that is the way it came out. They

had chosen him because he was the smallest man ever to enter West Point, his height

having been waived because of the lump of tinâthe

Congressional Medal

of Honor

, no lessâhe had won as an enlisted man (under age) in

the war.

They had needed a topographer who wouldn't subtract from

payload. Space travel was to begin with seeming to create a demand for a race of

small men. But he didn't tell the general this and they came to the end of the

ride.

T

he aide expertly ushered Angel

out into the bleak blackness of the takeoff field, where every officer and

newspaperman who could wangle it was all buttoned up to the ears and massed about

the whitish blob of the ship.

The flight surgeon took over, and protected Angel from the back swats

and got him through to the ladder. The two smallish master sergeantsâWhittaker and

Boydâwere waiting at the top in the open door of the ship. Metal glinted beyond them

in the lighted interior.

Whittaker was methodically chewing a huge wad of tobacco and Boyd was

humming a bawdy tune as he stared up at the romantically round and glowing moon in

the west. They were taking off away from it for reasons best known to the US Navy

navigators who had set the course.

A commander was hurrying about, muttering sums, and he paused only long

enough to glare at Angel. “Don't touch those sets!” he growled, and rushed off to

take station at the pushbutton which, when all was well, would fire the assist

rockets under the carriage on the rails. These were keyed in with the ship's

rockets. The commander glared at his ticking standard chronometer.

The flight surgeon said, “Well, you've got a week to sober up, boy. You

won't like this takeoff.”

Angel gave him a green smile. It hadn't been the champagne. It was the

apricot

cordial

that Alice had brought him to take along. “I'll be

fine,” said Angel, managing a ghost of his lovely smile.

“Board!

” shouted the commander.

Angel went up the ladder. Whittaker spat out his

chaw

and lent a

hand. Boyd was standing by on the stage and, more to avert the necessity of having

to see Angel's poor navigation than from interest, turned a powerful navy night

glass on the moon. Boyd was very fond of Angel in a cussing sort of way.

But Angel made it without help and had just turned to give the faces,

white blurs there in the floodlights, a parting wave to the click of cameras when

Boyd yelled.

“Oh, my aching aunt!”

There was so much amazed fear in that shout that everyone stared at Boyd

and then turned to find what he saw. Angel found Boyd shoving the glasses at

him.

“Look, Lieutenant!”

Angel hadn't supposed himself able to see a thousand-dollar bill, much

less the clear moon. And then he jumped as if he'd been clipped with a bullet.

The commander was howling at them to batten down but Angel stood and

stared, glasses riveted to the lunar glory.

Those with sharper eyes could see it now. And a wail went up

interspersed with awful silences. Even the testy commander turned to stare, looked

back to the ship and then whipped about to snatch a quartermaster's glass from his

gunner. He took one look and froze in silence.

Every face was uplifted now, the field was stunned. For there

on the moon in print which must have been a hundred miles high, done in

lampblack

, were the lettersâ

USSR