One Train Later: A Memoir (8 page)

Read One Train Later: A Memoir Online

Authors: Andy Summers

Tags: #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Guitarists

Arriving at Waterloo, I am overwhelmed by the size of the station and the grey mass of city beyond and almost get back on the train to return to the west, but with a beating heart, I ask a black-capped porter the way to Charing Cross Road. He leans down and says, "Toob to Tottenham Court Road and jump aht there, aw right, Sunshine." I thank him and wander down the platform, having understood nothing. Eventually, and after asking many strangers, I grasp that the tube is a train, not a thing full of toothpaste, and it's down there-underground. And so by getting little niblets of information, I arrive on the right train and eventually (with several people now guiding me) manage to jump out at Tottenham Court Road and make my way south to Selmer's. The shop is large, impersonal, and intimidating, and I feel about as significant as a fly on the side of Westminster Abbey. The guitars, the bored-looking salesmen, the whole ambience, makes me as nervous as a rabbit, but hanging on the wall like an Aztec sun in all her sunburst glory is a Gibson, an ES 175. With a pulse pounding like an African drum, I croak, "Can I see that?" to the salesman who has diffidently asked me what I want. "You want to see `that' guitar?" He looks at me incredulously, as if I have just asked for a date with Rita Hayworth. "Christ," he mutters to himself, but reaches up and unhooks it. I try a few chords-it's great, it's miraculousand as I run my fingers over the neck it is as if angels whisper in my ear, The future begins here. I look up at the lapels of the blue suit. "I'll take it," I say with a grin.

On the train home I sit churning with excitement, gripping the handle of the case; there is no way I am putting this on an overhead rack or letting anyone get near it. Back in my bedroom I unveil my new bride in all her honeyed splendor. Lying there in the crushed pink velvet case, she's a perfect musical machine. I gently remove her from her bed and stroke a few chords, gm7, C7b9, FM7#1 1. The smell of new wood drifts into my senses like an ancient forest perfume, something takes wing, and I play the intro to "Move It."

Two weeks later, on a beautiful late October day, I arrange to meet a girl in the local park. Wanting to impress her, I decide to take the 175 along and show off with a few chords. We sit on the bench together like Romeo and Juliet. The wind is sending a cascade of red and brown leaves down from the trees across the grass and around the bench where we sit, me holding the guitar. The girl, Natasha, has long blond hair, a face with a hint of Russia, and the promise of a heartbreaking woman. She sits close to me and I feel her heat. I am desperate to kiss her and I try to play something for her on the 175 and am so overcome that I play badly, but she pulls a leaf from her hair and murmurs as if in assent. On an impulse I put my arm around her and pull her toward me with closed eyes. "No," she says, and lets out a loud laugh and takes off across the park. I put the guitar down and take off after her into the streets that lead to her house. She runs like a deer, and in the twilight I lose her. I run back to the park to get my guitar and go home. But when I reach the bench, there is nothing there except a few more leaves. She's gone. My ES 175-disappeared. In hallucination I run my hands over the wood of the bench. I feel sick, the guitar of my dreams lost forever. I walk home numb and shocked and go through a tearful and wrenching scene as I explain to my parents what happened. My dad immediately calls the local police station, and they agree to go out and look for it.

Days pass and nothing turns up. I become very quiet, stay in my room, and experience a black depression. I stare into space and strum listlessly on the Uncle Jim Spanish, but it brings me down even more. I lie on my bed and stare at the ceiling. Maybe it's a first lesson: a rite of passage, a convergence of guitars and desire-the fatal mix of frets and femme fatale-a marker of the future. Or maybe I should just pay more attention.

Meanwhile, the local constabulary-good lads-scour field and hedgerow for the stealer of my dreams and come up with nothing except a blank expression. But the universe turns and one day, as if a double six has fallen on the roulette wheel, I hear my dad in the hallway talking into the huge black rotary thing that he calls a telephone. "Yes, I see ... oh, well, hmm ... yes, of course, I'll tell him." It doesn't sound too good. There's a knock on my bedroom door as I morosely play. My dad frowns and does his best Captain Bligh imitation, but he can't keep it up-he starts grinning and says, "The bastards are going to cough up." I let out a moan and roll off the bed in a mock epileptic fit. He smiles and quietly closes the door; whether it's relief or madness, I don't know, but I stand in front of my small pile of LPs, touch them, and then begin laughing as tears roll down my cheeks.

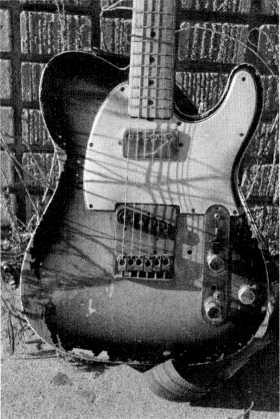

With the insurance company money safely deposited, I return to London and get my second Gibson. This time, now under the influence of ultrahip New York guitarist Grant Green, I buy an ES 335. The 335 is an innovative guitar that Gibson designed in 1958 and is slowly being accepted as a pretty cool instrument. They have come up with the concept of a semi-solid: a slimmed down version of an archtop jazz, maybe in answer to Fender's highly successful line of solid-body guitars. Not much more than two inches deep, it features a double cutaway that allows the player access to the highest frets and is a slick, fast guitar with two double humbuckers. In fact, the 335 turns out to be one of the best guitar designs ever, and from its humble beginnings in Michigan it begins its inexorable diaspora. How was I to know in this breathless moment as the first 335 passes into my hands that in the distant and magical future, Gibson will one day manufacture one of them as the Andy Summers Signature model? If the spirit had whispered into the sixteen-year-old's ear at that point, it would have been a cosmic joke.

Four

Right after I get my 335, Thelonius Monk arrives in England to play a concert at Fairfield Hall in Croydon, and I travel up to London by train to see him. After fifteen or sixteen hours of marvelous food and luxury travel with British Rail and several tricky station changes, I finally make it to the concert hall. On the bill are not only Monk but Dizzy Gillespie and Roy Eldridge. I am thrilled by all of it and love the jubilant sound of Dizzy and Roy playing "Groovin' High." But when Monk comes on and plays a solo rendition of "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You," it's as if the sun rises in my head. Monk plays from another place, pulling the order of notes and the sequence of chords from some private cookbook. With odd syncopation, minor seconds, and upside-downness, he creates a cracked perfection that hits me as the essence of jazz-the central message-and he does all this with big flat hands splayed out on the black and white keys to create a music that is beyond anything I have heard from a guitarist (or any other instrument, for that matter). Monk's playing cuts to the core experience of American life. After this I collect more Monk albums and become a lifelong fan, eventually recording my own album of Monk music, Green Chimneys.

Gradually my local reputation grows and I get invited to play at dances and private functions around town. For me, any chance to play is good enough, and I grab them like a man getting an extra slice of birthday cake. One night, driving back from a party I had played at in a village hall in the New Forest, Lenny (who has undertaken the task of driving me, my guitar, and amp out to the gig) turns to me in the front seat of his Morris Minor and says, "You know, if you keep practicing, you might just ... ," and his words trail off, but I get it-this is benediction from on high. A small sob almost appears in my throat, and as we drive on through the night back to my parents' house, the stars above appear unusually bright and clear.

There are a number of young musicians in the town, and I try to form little groups with anyone who will play with me. My friend Nigel Streeter plays alto sax, and the two of us-both Sonny Rollins fans-spend hours listening to The Bridge, Sonny's latest recording. The word is that Sonny has spent two years away from the public, during which time he sat on New York's Williamsburg Bridge and practiced for hours every day, his horn sending myriad streams of notes out over the East River. He has been searching, trying to take the music to another place, trying to move beyond the conventions, and refusing to come back until he has something to say.

We are inspired by this idea: the search for truth through music, the quest for higher consciousness, the concept of transcendence. Although we are only half aware of them, these ideas are beginning to float in the air like pollen. Kerouac has written On the Road and The Dharma Bums, Esalen has been established, and Timothy Leary is being fired from Harvard for his experiments with LSD. There are murmurings in the pages of Down Beat of Asian spirituality and Eastern philosophies beginning to infiltrate the music scene, and suddenly it seems as if all the hippest cats are embracing Buddhism, Sufism, Islam, and yoga. It all sounds very exotic, and we ponder phrases like avatars of the new consciousness and wonder what that means. Avatar? It sounds like some kind of trombone.

The jazz community, with its long history of pot smoking and heroin, is a natural place for this to start. Altered states may arise from strict spiritual disciplines but are more likely with the imbibing of drugs, things with weird names like horse and tea. We sprawl on Nigel's mum's Axminster among endless cups of Darjeeling and Pontefract cakes and read articles in Down Beat about withdrawal, cold turkey, or monkeys on the back and musicians who have bad colds or are heaped to the gills. Rather than jazz, it sounds like the zoo or the butcher's shop or a visit to the doctor. But it is the quest, the search, that inspires us and we play the new Rollins LP over and over. We don't speak much with our parents about this world; it belongs to us, and our mums and dads, as they busily vacuum, dream about Sunbeam Talbots, and plan next summer at Butlins, are somewhere back in time-lost in a Pathe newsreel. We ignore the fact that they have survived the Second World War and may have spiritual reserves of their own, and in the arrogance of youth and the pebbledash frame of suburbia, we guard our secret code with grunts and snobbery.

Sixteen, and as my skin breaks out and I turn my collar up James Deanstyle, my brain becomes a pastiche of bebop, Kerouac, Down Beat reviews, skyscrapers piercing the New York skyline, girls, women, dolls, chicks-the whole beat scene.

I get a job in the summer as a deck-chair-ticket collector on Bournemouth Beach and each afternoon wander through the crush of arms, legs, and perspiring foreheads to collect beachgoers' money, which goes to the Bournemouth Corporation. All day for seven pence. I realize that I have power over these poor begotten lumps trapped in striped canvas-I could turn in those who try to get away with not paying. But standing in the sand in a white corporation attendant coat and a heavy leather satchel around my neck, I punch tickets with a headful of riffing horn solos, foreign films, and the breasts of Brigitte Bardot. The red-faced mums with sticky little kids in the sand at their feet barely make it onto my radar.

"Hey, man, don't just stand there dreaming." A voice from behind penetrates my sun-bleached hallucination. It's Kit, another corporation employee but a guy who is different from the rest of us. He walks about in a cool, detached way, and it's rumored that he is a poet. He doesn't appear to have a home but carries all his worldly possessions in a small backpack. I work up the courage to talk to him one day and he gives me a small grim lecture about being beat, which he says is a state of mind and that to be cool, to be on the outside, is to be hip and the two things-hip and cool-combine to make you a hip outsider, who is cool, the very essence of beat, cool. The hip don't have regular jobs, don't get mortgages, don't buy bungalows, don't buy into this whole crock we call the straight world, man, they just keep moving.

A 250-pound woman heaves herself out of a deck chair with a struggle, and Kit swiftly slings it on top of the stack he is making. "Burroughs's Naked Lunch-read it," he says, spitting in the sand, stacking another deck chair. The sun sinks behind the pier in a swirl of circling seagulls and I feel a deep sense of insecurity, but I look at Kit and nod in an impassive but knowing way, in fraternity-yeah, brother. This deck-chair thing is just for kicks. But this thing that he's got in spades, I want it too; I desperately hope that playing jazz is cool-it must be, jazz musicians call each other "cats." I am very impressed-how could this guy know all of this? I decide to get a backpack.

I begin grunting in monosyllables, barely parting my lips to speak, and take to wearing sunglasses inside the house, even when sitting on the end of the bed practicing. "lire your eyes hurting again, dear?" my mum asks anxiously-or so I think, although she is probably smirking behind her hand. "Better pop down to the optician's with you, then." I merely grunt back in her general direction as I struggle with C7b9. I read On the Road and The Dharma Bums. I don't really get them-it's another world-but I take in their aroma and realize that my fellow deck-chair stacker is the personification of Japhy Ryder, Kerouac's protagonist from The Dharma Bums.