One Train Later: A Memoir (17 page)

Read One Train Later: A Memoir Online

Authors: Andy Summers

Tags: #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Guitarists

We are introduced in the dark. He's soft-spoken and shy: the music is something else. Chas quickly forms a band around Jimi consisting of Mitch Mitchell, a very good drummer but an unusual choice with his jazzy style, and Noel Redding, who is essentially chosen for his hair. Within a very short time everyone is talking about Jimi, and the word spreads. He puts out his first single and gets a hit, and the world embraces him.

I see him from time to time for a couple of different reasons. My girlfriend at the time is best friends with Kathy Etchingham, who is Jimi's girlfriend, and there are moments when we end up in a club together because of the women. On a few occasions I end the night in Mike Jeffries's flat, where Jimi lives, and I sit on the bed with hirn as he speaks softly and gently strums the Strat, which never seems to be out of his hands.

One night Dantalian's Chariot has a show at the Speakeasy, a very popular club in the West End. Generally the crowd at the Speakeasy are hard-core musicians and music-biz types. The club is small and crowded, with a stage about the size of a dog kennel. We are announced and emerge from the dressing room to blow away these music-biz types. Sitting right in front of me, literally no more than four or five feet away, is Jimi with a couple of girls. By now he is probably the most legendary guitarist in the world and I have to perform the entire concert with him right there under my nose, staring at me. It's unnerving, to say the least, and consequently it's probably not the most career-building playing I will ever do. We finish and I run into him a few minutes later in the men's room, where we stand side by side relieving ourselves. "Yeah, man, cool," he says as he pisses away the last three scotch and Cokes.

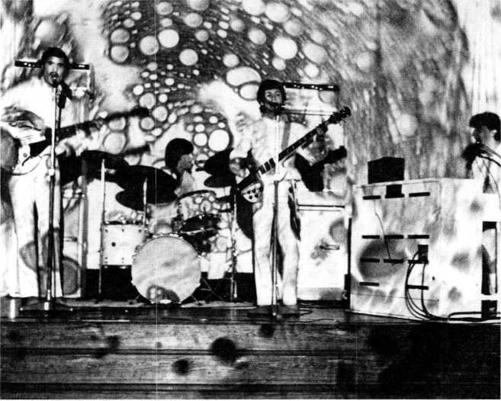

Providing our oil-slide light show are Mick and a wild man named Phil. Mick is tall and very thin and has borrowed the money from his father to provide the equipment. Phil is the artist and the one who does the actual projection. Phil dresses in whatever comes to hand, has a wild and shaggy appearance, speaks with a BBC voice, and has an enormous appetite for drugs. He swallows hallucinogenics and other substances by the handful, washes them down with great gulps of alcohol, and then takes off on hinges of three or four days' duration without sleeping. What would have killed most people doesn't seem to affect him. A Herculean character, Phil is also very entertaining, and sometimes it seems that he is the one who should be onstage rather than us.

We are eventually able to put his unconstrained personality to use when we arrive at the port of Copenhagen for a Scandinavian tour. To get publicity and create some static, we have decided beforehand that as we arrive, we will have Phil, dressed only in a bearskin, on the end of a steel collar and chain being led by Mick, who will be wearing a white safari outfit complete with pith helmet. Naturally enough, Phil rises to the occasion; in fact, he rather overdoes it. As we pull into the port, drifting past the Little Mermaid with the strains of "Wonderful Wonderful Copenhagen" filling my ears, Phil smashes his chain into the plank and begins leaping and cavorting about the deck. He rolls across the steerage to the feet of lady passengers with an intimidating leer on his face and then, howling like a wolf, leaps into the lifeboat to perform apelike challenges to the crew by showing them his ass. He rounds this off nicely by dry-humping the mast and simulating orgasm until it becomes quite doubtful as to whether we will be let into Denmark. Later Phil just grins innocently, asking if he went too far, and then swallows something purple.

Our theatrical efforts have, however, interested a gentleman by the name of Sean Murphy. Sean has apparently worked at the National Theatre, done Shakespeare, and comes with a prestigious theater pedigree. We come together because he is supposed to put on a show in Paris that involves pretty much anything of a psychedelic nature. The performance concept is that two groups will play onstage together at the same time to create a duel-a clash of bands. The lucky bands chosen for this visionary idea are us and the Yardbirds, and we have an initial meeting with Sean at our mangy flat. A charming and polished middle-class chap, he describes his ideas to us in a very theatrical way. He talks about prisms, arcs, curves, and sweeping forms, and from this moment on he will be known forever to us as Sweeping Forms Murphy. This is usually expressed with a grandiloquent Shakespearean gesture and a long drawn out "daahling." Now we take great delight in pointing out sweeping forms to one another, noting that in fact the universe is alive with them and may be seen even in something as mundane as a dog turd lying in the street.

Jimmy Page turns up one day to discuss the possible musical interaction between us and his group, the Yardbirds. He is gentle and intelligent, and I remember how he let me borrow his Les Paul Black Beauty to sit in at the Marquee. We hang out in my basement bedroom and he admires my collection of books on Zen and various mystical philosophies. He too has an interest in this area and later starts his own occult bookstore in W8.

The show with the Yardbirds doesn't happen, but Sean gets us to Paris anyway on a great sixties extravaganza called La Fenetre Rose, an indoor festival of psychedelic music, happenings, dance, film, light shows, and enough drugs to sink the British navy. Something like thirty English rock groups are scheduled to play, and it promises to be an event that will stay in the memory-if memory remains.

Two weeks later on the drab grey platform of Victoria Station among advertisements for Tit bits, Omo, tipped Woodbines, and Cornish Dairy brick ice cream, we-a ragged multihued army of young musicians-come together like a cluster of monarch butterflies milling about in the station, bonding and smiling in recognition of the extraordinary weekend it promises to be. We are all on the same trip and beatific in our assurance that we are the revolution. Robert Wyatt, the drummer of the Soft Machine, approaches me and tells me that he admires my solo on a track we have recorded called "The Mound Moves," that he listened to it on a jukebox in Kent and has always wanted to play with that guitarist. He is funny, and self-deprecating. I'm flattered by his remarks, attracted to him, and immediately become interested in hearing his band.

As the clock strikes the hour, we leave Victoria for Paris-a blue cloud of hashish, twanging guitars, ribald jokes, velvet, caftans, loon pants, and highheeled boots. It's nine o'clock in the morning.

In Paris we play at Olympia. La Fenetre Rose is an all-night extravaganza of trippy lighting, wafting clouds of incense, pulsating music, and painted faces. With music, color, light, and the chemical message coming together in a brilliant synesthesia, it's a celebration of throbbing tribal intensity.

I wander in and out of the backstage area and out into the crowd, where the heat of the bodies, the forest of faces painted with whorls and symbols, the thick smell of hashish, and the pulse of the electronic dance combine to make me feel as if I am levitating. Onstage a beautiful woman appears in a flimsy diaphanous tunic and slowly disrobes to the sound of a violin a few feet away. The Soft Machine take the stage. Mike Ratledge pushes his arm into the keyboard to make a large rainbow-colored dissonance and they crash into their set with Robert Wyatt's soulful vocals arching over the angular harmonies.

We play, and the performance passes like a dream, with music, light, bodies, and minds fusing into a synaptic meltdown. We end the set with our strobe lights pulsing like two white sums and float offstage hardly knowing we'd been there. I drift off with a crowd of French hippies and a headful of hashish to lie on the floor of someone's hotel room, Ravi Shankar's sitar droning in any head like a buzz saw.

After playing a show in Cornwall one night, we spend the night in a nearby hotel. A friend of ours-Vic Briggs, the guitarist with Brian Auger-comes to see us, saying that he has something special. Naturally enough, before the adrenaline of the gig wears off, we end up hanging out in someone's room and getting festive. Vic pulls out some acid that he says is especially good, just in from the States; it's called Window Pane and, well, why not? We each swallow a tab, all of us except Vic, who surreptitiously palms his. (And I will always feel suspicious of this cunning move.) While we crawl around the room in a deranged state, he merely observes. The night unfolds with the usual set of extraordinary fantasies, hallucinations, and insane laughter. Vic puts on an Indian film music LP called Guide, which apparently is a big hit on the subcontinent. He plays a track called "Piya Tose," a glorious piece of music and arranging with a beautiful Hindi vocal sung by the incomparable Lata Mangeshkar.

This track is so transcendent to me, so utterly joyful, that I ask for it to be played over and over again for what (under the time-stretching effects of Window Pane) seems like hours or even years. The acid takes me to a place somewhere in the South Pacific, where I sit in the prow of a dugout canoe that is being paddled by a team of young and bronzed Tahitian natives. It's a drug hallucination, but so vivid and intensely happy that it is printed deep into my cortex, never to be forgotten. In the distant future I will record that song on an album called The Golden Wire with the beautiful Indian singer Najma Akhtar.

The night progresses or, rather, descends, into a prismatic fantasy. After a brief episode of working in a wheat field in late-sixteenth-century Germany, followed by running with wolves in the Arctic Circle, I put myself into the lotus position. With a realization as deep as the ocean, I understand that this, the lotus position, is the ancient key to life. From this revelation I begin to experience birth (maybe I have cramps after sitting in the lotus for a while) but-and this is discussed in the Tibetan Book of the Dead-I suddenly start going through a process that somehow I know or remember from before as parturition-birth. In Tibetan terms it is referred to as the birth and death. of the ego-two sides of the same coin.

Appearing to us as a place we have occupied before and after the end of time, the room we are crawling about in has, in typical good English taste, floral wallpaper that not only covers the walls but also the doors and ceiling. This creates the effect of having the walls of your brain pasted with flowers, which is heavenly but also really fucks you up. At one point I open what I think is a door to the bathroom but end up stepping into a clothes closet for a piss. Pissing while on acid is an experience all its own. Staring at the pink shriveled thing lying in your hand like a baby carrot, you wonder who it belongs to and what it is. But whatever, it's cute. If you actually manage to urinate, you will observe the golden stream with wonder and see its great beauty arcing forward in an infinite rainbow and the mind of God at work in all his mystery and power. Flushing is probably forgotten but if attempted will be greeted with childlike awe and glee and then repeated as many times as possible until someone gently guides you away. This Cornish night ends with us slumped in great flower-covered armchairs like men who have traveled a vast distance and now, like the flowers themselves, slowly fade and wither.

Toward the end of our sojourn as Dantalian's Chariot we do a minitour of Scotland-two gigs actually. We cross the border slumped in the van in various states of disarray. After a long day's slogging drive from London and with bellies full of fried bread, Heinz baked beans, eggs, and sausage a la transport cafe, there is a suspiciously sulfurous edge in the air and someone suggests we rename ourselves the Farting Zombies.

At this point we are heading into the Cairngorms and hopefully to a place called Craigellachie, the location of the gig. We study the map and find that apparently it doesn't exist; this, of course, would be par for the course, the ineptitude of an office secretary, a misspelling, tea spilled over the word we are supposed to decipher. No doubt we are meant to be in Caddiff but naturally we are in Scotland. We can't find it on the heavily creased and misfolded rag that is our map. Like an ancient Celtic code, it is nothing but dark brown patches covered with unpronounceable Scottish names and circles describing the heights of the mountains.

It's getting late. Out on the hillsides kindly old shepherds are herding their flocks back to the farm after a hard day's sheep shagging in the heather, and as the sun begins to sink behind the ancient mountains and we are faced with the sturdy reality of the Scottish hillsides, our garish psychedelic clothing and benumbed state suddenly feel rather ridiculous. A strong pair of brogues, thick kilt, tweed jacket, a pipe maybe, a keen eye for hawks, would feel right, not the bright-red-and-yellow pantaloons, fringed jackets, shoulder-length hair, and mascaraed eyes. Laird of the glen material? I don't think so. The argument over "where the fugawe" continues, and I decide to retire from the bother of it all knowing that surely we will arrive there somehow. I'm in an intense Zen phase, full of koans, satori, and lines from Basho, and rather smugly I lean back into my seat, trying to savor the moment in all of its cracked perfection.

Fine people, the Scots, I think to myself as I open The Three Pillars of Zen by Philip Kapleau and begin to read, "The mind must be like a well-tuned piano string taut but not tight." I sit up straighter in my seat and imagine my mind growing taut and aware just as we narrowly avoid an entire flock of sheep coming unannounced around the narrow bend. "For fuck's sake!" I yell as we swerve and miss death by wool by a mere inch or two. "Shit-very fuckin' taut," I curse to myself. I read on: "Nirvana is the way of life which ensues when clutching at life has come to an end." Any more near misses like that last one and I'll get this first, fucking-hand, I think. "To attain Nirvana is also to attain buddhahood." "Yr nae goon tha right was y shouldna hae com this fargit y se turned aboot." We have skidded to a halt about two inches in front of an abundant hedgerow, and I look out the window to see a small, oddly dressed gnome in a kilt gesticulating with vigor at the road behind us. The next forty-five minutes may be neatly summarized as follows: "to know by seeing, to become cognition, to become truth, to become vision-this is the ideal," "yr no on the right roade, y' shouda turned left by McCocelby's farm," "the supreme form of knowledge is knowledge conforming to reality," "git to fuck," "realization of the voidness, the unbecome, the unborn, the unmade, the unformed implies buddhahood, perfect enlightenment," "can ye lend us a quid, ahm dyin `for a wee drink,"' "form is no other than emptiness; emptiness is no other than form." And then, "Ye no sayinit right, `Craigellachie' "; with the fizz of an exploding lightbulb, a Krishna wave of enlightenment passes through the van. Sid, who is driving the van and also our chief inquirer of directions, has been asking the way by leaning out of the driver's window and asking in a thick South London accent, "'Scuse me, mate, know a place called Krajer- latchi?" The Scottish pronunciation that at last we hear correctly is a tight small word that is perfect in form. It is issued like a tight musical phrase from the back of the throat--imagine late Sean Connery. Through ignorance and ineptitude, we have just wasted two hours being lost in the Scottish mountains. "Take a wee right, lads, jes right up the road here and follow tae signs." I put my book down, stretch, and yawn as evening slips into night and we sail into a small Scottish village.