One of Us

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINETEEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY

- CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

- CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

- CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

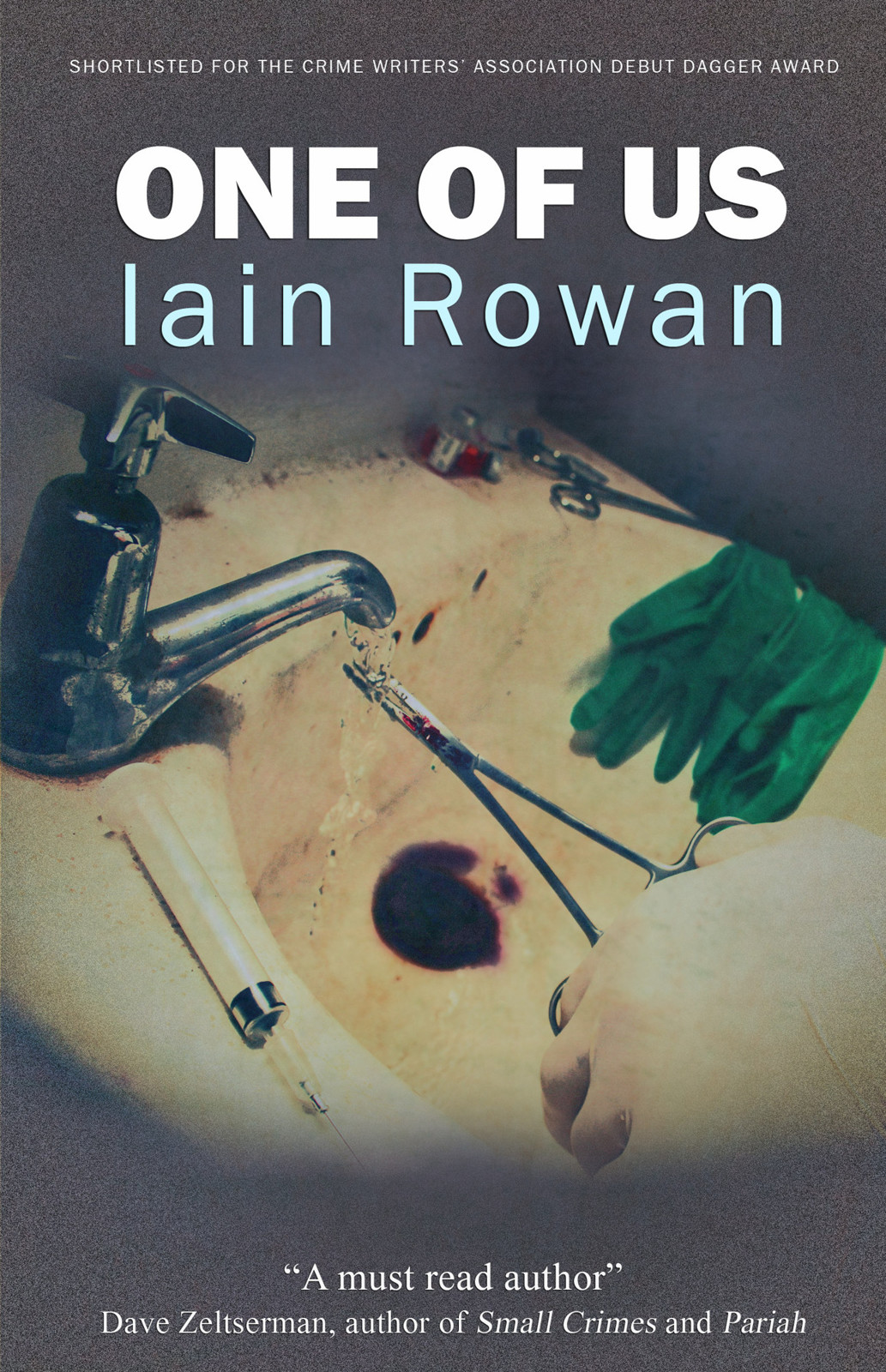

One of us

Iain Rowan

One of Us

Anna is one of the invisible people. She fled her own country when the police murdered her brother and her father, and now she serves your food, cleans your table, changes your bed, and keeps the secrets of her past well hidden.

When she used her medical school experience to treat a man with a gunshot wound, Anna thought it would be a way to a better life. Instead, it leads to a world of people trafficking, prostitution, murder and the biggest decision of Anna's life: how much is she prepared to give up to be one of us?

Shortlisted for the UK Crime Writers' Association Debut Dagger award,

One of Us

is a novel by award-winning writer Iain Rowan.

Published by infinity plus at Smashwords

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© Iain Rowan 2012

Cover design © Keith Brooke 2012

Cover image © Wessel Du Plooy | Dreamstime.com

ISBN: 9781301596911

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy.

Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Iain Rowan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Electronic Version by Baen Books

CHAPTER ONE

Twelve months more of medical school, back in my country, and I would have been a doctor. Here, I scrape grease from a stained griddle under buzzing lights, while drunks stagger and shout on the other side of the counter. When they vomit on the tiled floor, I have to clear it up, with a metal bucket and a mop that is falling apart. Maybe this is not so different to a hospital on a Saturday night. Thinking this helps, sometimes.

Before the burger bar I worked in a cheap hotel, stripping stained sheets and emptying ashtrays for three pounds an hour until the assistant manager came and closed the door behind him, and smiled while he undid his belt. If the old couple had not returned to argue about who had left their theatre tickets behind, I do not know what would have happened. Or rather, I do.

Before the hotel I scrubbed left-overs that were worth more than I was from dishes in a restaurant, and before that I shivered on the streets for four nights that lasted a year. Before that was a boat, and before that, days in the back of a lorry. Even now, if I smell lemons I also smell diesel and fear. Before that was another lorry, and before that another city, and before that was the day that the policemen beat my brother to death, and dragged my father away to die in a prison cell, and I heard it all from the cupboard under the stairs, shivering behind an ironing board with my fist stuck in my mouth to stop my screams from coming out.

So I scoured grills, and burnt my hands, and I wiped half-chewed chips from plastic tables. No-one asked me for any papers, the work paid me money in my hand, and the money paid for a bed in a room in a hostel. I shared the room with three other women, and a small bathroom and kitchen with everyone who lived on the same floor, but there was a bed for me, and there was a lock on the door, and after the four nights on the streets that was enough.

Alice came from Kenya. She worked very early in the morning, cleaning in a hotel. She had a picture of a beautiful child stuck to the wall next to her bed. At night she touched it with her fingers as if she was touching the child’s face, and she cried without making any noise. Safeta was Kosovan, and she worked in a laundry, washing and drying a thousand sheets that a hundred Alices stripped from beds every morning. She smelt of the laundry, a clean and nice smell, but her hands were always red and she bled from around her fingernails. Sally was English but she was also a drunk. I do not know what she did in the daytime but at night she just slumped on a couch in the common room of the hostel, drinking cheap wine and staring through the television into a world beyond. Sometimes she had bruises and what looked like bite marks all over her arms.

If I lived there for too long I would go mad, and end up sitting with Sally by the television, pulling at my hair or picking at scabs on my arms. But without the proper legal documentation I could not get a better job, and without a better job I could not make more money, and without more money I could not live anywhere other than the hostel.

I could not go back; it was not safe for me. Even if things changed I could not go back. Would not go back. I could not live with so many ghosts. So I am here.

I save as much as I can from the endless nights in the burger bar to buy some papers that will say that I am legal. I do not want to do this, because I want to be a good citizen, and because the men who deal in the false papers remind me of the men at home: they do everything with a swagger that says that anything that gets in their way will be beaten out of it. I do not want to deal with them.

But I do not want to go back.

Daniel was not one of those men, but he worked for them. He was all smiles and loves and sweethearts and he laid his hand on my arm as if he were my friend. Safeta knew a Kosovan who would not deal with me, but he gave me a phone number, and I rang it and spoke to an English man who did not give me his name, not then. I met him three days later in a busy coffee bar at the railway station. He was tall and slim, and the way that his black hair fell loose over his forehead made me think of a boy that I had known in school.

“I’m Daniel, sweetheart,” the man grinned. “Just Daniel.” He sat opposite me, sipping at his coffee, smiling at me a lot and looking at me a lot, and asking me questions about what I wanted. The cafe smelt of coffee and warm pastries. Daniel asked me why I did not have a drink.

“Because I do not want one,” I said.

“Don’t have the money for it, more like,” he said, shaking his head. “Come on, don’t lie to me, sweetheart. How can I trust you if you lie to me? And I want to trust you, really I do.” He leaned over, rested his hand on mine for a moment, just a moment, and then took it away.

“I cannot tell a lie,” I said. “It is because they use Robusta beans for this coffee, and I prefer Arabica. I am fussy that way.”

He smiled, a perfect white smile that I could tell he had practised on many girls before. I thought that it would usually have worked too, that and the way he held eye contact just that little bit longer than necessary. Once, it maybe could have worked on me. But not now. I was too tired, too busy just living, for anything like that. “So if you can’t even afford a cup of this slop, how exactly were you planning on paying me?”

“That is why I do not drink the coffee,” I said. “It is why I do not buy newspapers, or cans of cola, or anything except for rent and food. So I can save the money, so I can get what I need.”

He liked my answer, because he laughed a lot and bought me a cup of coffee and told me that he liked my spirit. He asked me where I came from.

“I come from North Ossetia,” I said, and Daniel made a face and shrugged.

“Russia,” I said. “To most people here, just Russia.”

“Don’t think I know it,” Daniel said.

“You won’t,” I said. Most people do not, and to them it is all just Russia and Russians. The one thing that people know about my country is the school called School Number One. This school was in a town called Beslan. But I do not like to talk about what happened there. “My home was in a city called Vladikavkaz.”

“I know that name,” Daniel said. “Why do I know that?”

It was my turn to shrug. When I did, I caught him looking at how my breasts moved under my sweatshirt. He gave a little grin of no apology but an acknowledgement that he had been caught.

“Think United played there once, didn’t they, mid-Nineties?”

I folded my arms, and then shrugged again, I am not here for small talk, do I look like a woman who cares what United did? Anyway, it was Liverpool, and we lost to them. Aleksey took me, kept threatening to embarrass me by holding my hand when we were walking to the stadium.

“So what did you do Anna, back in Vladiwhatever.”

“I was a medical student,” I said. “I was studying to be a doctor.”

“Were you now,” said Daniel, and he did not seem very interested in talking about it, because all that was past and gone, so I did not say anything else. I remembered when I was at school, studying hard for exams. I was sat at the kitchen table, my books spread everywhere, a cup of tea gone cold, when my father came in. He stood and watched me for a moment, not saying anything.

“How’s it going?” he said in the end.

“Lots to do,” I said. “And I’m tired, can I not—”

“No,” he said. “You can not.”

“But I haven’t—”

“You don’t need to. Listen Anna, your schoolwork is important. You pass these exams, as I know you can, and there will be a place in the Medical Academy and you will be a doctor, Anna. Think of that, a doctor.”

“I know,” I said, sulking because I wanted to be a doctor but I also wanted to be out with my friends. “But—”

“If your mother could see you a doctor,” he sighed. “She would be so proud.”

And that was the end of that. I could not argue any more, because I knew that he was right. She would have been.

My father placed a hand on my shoulder.

“Study hard, Anna. I know I seem like a tyrant. But my daughter, a doctor. I will be so proud, too, to see you do something with your life. Something better than I do.”

I stared down at my books.

“Yes,” he said in the end. “Well, dog won’t feed itself.” And he stomped off, out of the kitchen, and I went back to my work because I wanted so much to pass those exams, but it was hard to concentrate when my vision was so blurred.

Daniel bought me another cup of coffee even though I said no, and then he named a price that I could not afford.

“I do not have that much,” I said. “Not nearly that much.” Can you not tell, I thought. Look at me, look at these jeans, which cost less than I would once have spent on a pair of tights. Look at these hands, with their bitten nails and their red marks from hot grease. Once, everyone in this place would have looked when I walked in. Now, they probably think that I am staff, on a break.

He shrugged, flicked his hair away from his forehead. “You’ve got a problem then. I really do want to help you sweetheart, but that’s the price. I’ll throw the coffees in for free. You’ve got my mobile number. Phone me when you have the money. We’ll do business.”

“It will take me a long time,” I said. “When I pay for food and rent, there is not much left to save.”

“Girls manage,” he said, “they find ways,” and he gave me a long look over his smile. I went back to work, and ate food that customers had left so that I could save more money, and I slept, and I did not do much else.

~

A month later I was working the evening shift again, slapping a mop around the floor in front of the counter and trying to replace the stink of vomit with the smell of bleach. Rain rattled against steamed-up windows. Sean slouched at the till, deep in a library book about ancient Rome. The week before, it had been a library book about astronomy. His obsessions changed with the weather.

I met Sean on my first day at Peter’s restaurant. Peter handed me my uniform of bright red shirt and itchy grey trousers, and told me that he was going to be very busy in the office, so one of the team would show me how everything worked.

“Sean,” he said. “This is Anna. Show her the ropes, will you?”

A tall, thin man with scruffy hair that wasn’t the colour of anything in particular took an awkward step forward, like a heron. He held out his hand, and I went to meet it but my own hands were in my pockets and by the time I got one out he had blushed and dropped his hand, thinking that I did not want to shake hands, and then when I did hold my hand out again, he had put his in his pockets. He said, “Oh, sorry,” and blushed again.

“Sean,” he said. “Um.” He waved a hand around the kitchen. “I work here. Good to have you around, we’re short on staff. Sorry, don’t mean that it’s only good to have you here because we need just anybody, it’s good to have you here as um, you.” He tailed off, coughed, scratched at an eyebrow. “Right. Anna, yeah?”

“Yes, I am still Anna.”

I regretted it when I said it, because I thought that he would be offended, and I did not want to offend this shy man who I would have to work with. But he did not look offended, he laughed.

“Good. Be a bit scary if you were someone else, really. Let’s start again and give the comedy routine a miss.” He smiled, and held out his hand again, and I thought: there is more to this man than there seems. Sean became the closest thing I had to a friend. He was well-educated, I think that he too had been to university, but he never spoke of it, and only ever talked of many dead-end jobs like this one. There was often a sadness in his eyes and sometimes his hands shook and shook until he put them in his pockets and clenched his fists very tight and I pretended that I had not noticed.

I plunged the mop into the water that was already dirty, and slopped it onto the floor because I was too tired to go and change the water. The door banged open and I felt cold air and then somebody standing near me, so I concentrated on mopping in circles around my feet, not wanting to look up, to have to see a leer and allow the chance for a conversation to start with a middle-aged man running to fat who did not often get the chance to talk to twenty-five-year-old girls running to skinny. I tried just to be a piece of furniture, without age, without sex, nothing to look at of interest. Since I had left my country, I had much practice at this. Not that it made much difference to many men. I was a woman, and so I was fair game. I could have worn a potato sack and not washed my hair for a month, and it would have made no difference to some.

“Forgot which burger place you said you worked in, didn’t I,” a voice said. “Fifth one I’ve been in. I’m getting soaked, and I’m sick of chips.”

It was Daniel. He grinned at my surprise, like a child who had just performed his first magic trick. I did not know what to say so I did not say anything. I do not want to talk to you, I thought. Not now anyway, when my hair needs a wash, and I am sweating into this stupid shiny red blouse that reflected the lights on to my face and made me look like I was blushing.

“So, this is your office,” he said. Peter came out from the kitchen and frowned at the sight of someone standing talking and not buying, but he dropped a cardboard box of plastic cups behind the counter, grunted at Sean to put the damn book down and follow him, and stomped away again. Peter was the manager of the burger restaurant. He made me think of a bear in the zoo at home, he was hairy and he growled, and whenever he came into a room it looked smaller. Sometimes he was kind, sometimes his temper scared me. I forgave him that, though. He gave me a job, without asking for papers or identity cards, and he paid me on time, and he did not try to touch me. He looked sometimes, but he never did more than that, and that is no more than most other men that I have known and it is much less than many others.

“What do you want?” I said to Daniel. “Why have you come looking for me? I do not have the money yet.”

“Got some good news for you on the money side of things, sweetheart,” he said. “You come with me now, but no messing around, it has to be right now, just do one little job, and you get a new identity, the full works, all the papers. Real, not fake, people on the inside, worth ten times what I quoted you for a knocked-together one. Make you one of us, as legit as me.”