One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (17 page)

Read One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America Online

Authors: Kevin M. Kruse

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Religion, #Politics, #Business, #Sociology, #United States

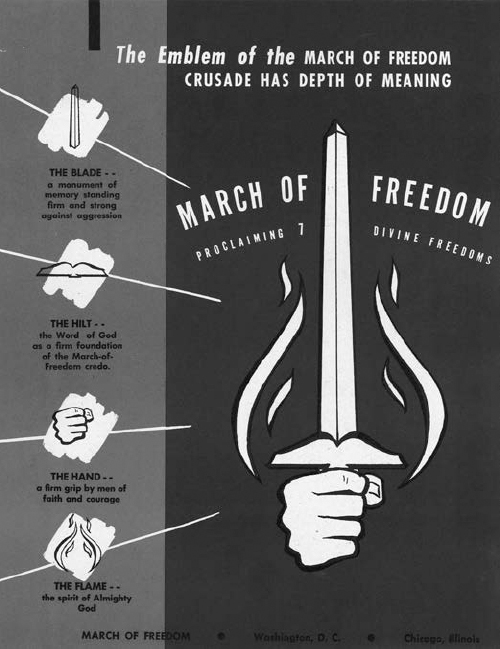

In July 1953, the National Association of Evangelicals arranged to have Eisenhower, Nixon, and other high-ranking officials sign a statement declaring that the United States government was based on biblical principles. In this promotional poster for this “March of Freedom” event, the Washington Monument is joined to the Holy Bible to symbolize the fusion of freedom and faith.

Courtesy of Wheaton College, Archives & Special Collections.

As the Fourth of July approached, the NAE promoted the event thoroughly. The Jaeger and Jessen advertising agency of Chicago blanketed the country with publicity that stressed Eisenhower's involvement in, and inspiration for, the movement. An early promotional booklet, for instance, repeatedly referenced the prayer he offered at his inauguration. “Our President touched a deep need of each heart when one day he voiced these words: âAt such a time in history we who are free must proclaim anew our faith,'” it read. “President Eisenhower's spark of faith set the fires of hope burning in the hearts of Christian people throughout the country.” Moreover, these materials stressed how other “leading Christian citizens” would be involved. Senator Carlson agreed to lead the national sponsoring committee, which had 177 members, one for “each year of freedom since the signing of the Declaration of Independence.” The group would encourage public and private leaders to sign the “Statement of Seven Divine Freedoms” and thereby signify that the United States of America had been founded on the principles of the Holy Bible.

42

Eisenhower was the first to sign, in an Oval Office ceremony on July 2, 1953. “This is the kind of thing I like to do,” he said afterward. “This statement is simple and understandable, and sets forth the basic truth which is the foundation of our freedoms.” Nixon added his name next, as did members of the cabinet. The administration's support was just the beginning of the document's journey. “It is being carried in a real

MARCH OF FREEDOM

to each Justice of the Supreme Court, and then the

MARCH

will include each state capitol, to be signed by the Governors,” the NAE reported. “As each capitol is reached,

MARCH OF FREEDOM

rallies will be held all through that state.” The document would travel across the nation, they promised, gaining support as it went, ultimately returning to the nation's capital for a major event at the base of the Washington Monument

on the following Fourth of July. “By means of the radio, motion pictures, television, newspaper and periodical advertisements, signboards and posters, essay contests and amateur dramatics as well as community rallies, sermons and editorials,” Decker insisted, “this theme âFreedom is of God and we must have faith in him' can constantly be dinned into the consciousness of America.”

43

The March of Freedom campaign was an unparalleled success, but the movement's underlying emphasis on framing Independence Day festivities as a religious event was, by this point, nothing new. In 1953, the “Freedom Under God” movement of Spiritual Mobilization entered its third year, beginning with a monthlong series of radio specials on the program

The Freedom Story,

local speeches and sermons on the theme, and festivities on the Fourth. Ever more popular with the public, the third annual festivities were sponsored by organizations such as the Amvets, the American Legion, Kiwanis clubs, Moose lodges, the Boys' Clubs of America, and the USO. Governors and mayors across the nation once again issued proclamations attesting that “our government is a government under God.”

44

At the same time, Eisenhower declaredâlike Truman before himâthat Independence Day would be officially designated as a National Day of Prayer. He had apparently planned on doing so from the start of his administration, but found himself following through after prompting from Bishop Fulton Sheen on his popular television show. In a May broadcast, the Catholic prelate reminded his millions of viewers of Eisenhower's inaugural address, in which “God was not an after-thought, but a pre-thought and a dedication.” “For this reason,” he wrote the president, they knew “you would be sensitive to the appeals of the American people for such humbling of ourselves before God, that we may be exalted as a nation.” The White House received so many letters urging the president to make the holiday a holy day that it issued what aides called “a blanket acknowledgment” in a press conference. A formal proclamation from the president soon followed, again designating “July 4, 1953âthe one hundred and seventy-seventh anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in firm reliance on God's transcendent powerâas a National Day of Prayer.” The president formally requested that “all of our

people turn to Him in humble supplication on that day, in their homes or in their respective places of worship.”

45

For his part, Eisenhower spent the day at the presidential retreat at Camp David. Though he had already done much to revive religion in national life in his first few months in office, critics seized upon his vacation as a sign of insincerity. “The greatest demonstration of the religious character of this administration came on July Fourth, which the President told us all to spend as a day of penance and prayer,” noted radio commentator Elmer Davis. “Then he himself caught four fish in the morning, played eighteen holes of golf in the afternoon, and spent the evening at the bridge table.” In truth, Eisenhower had gone to great lengths to find a place of worship near Camp David. “I sent out a scout to search the countryside,” he wrote a few days later, “to find for me a church that I could go for a short service. He visited six towns, only to discover that none of them was holding a special service on the 4th,” which that year fell on a Saturday. “I did get to church on the 5th, but it struck me that it was odd that the ministers in that region did not feel they could develop enough interest among their parishioners to make it worth while to have a short service on the 4th.” Despite everything Eisenhower had done to encourage a religious revival in the nation, much more work was needed.

46

T

HERE ARE FEW QUIET DAYS

in Washington, D.C., but Monday, May 17, 1954, was particularly frantic. For nearly a month, some twenty million Americans had been watching the dramatic showdown between Senator Joseph McCarthy and the United States Army in congressional hearings broadcast live on ABC and the DuMont network. But that morning, President Eisenhower stunned the nation by barring all Pentagon officials from testifying, and suddenly McCarthyism's climactic battle came to an abrupt halt. Then, only hours later and a block away, the United States Supreme Court issued its long-awaited ruling in the school desegregation case of

Brown v. Board of Education.

At 12:52 p.m., Chief Justice Earl Warren began delivering the unanimous opinion that tore down the constitutional foundation for racial segregation, speaking slowly but surely in awareness of the moment's importance. When he finished at 1:20 p.m., wire services sent the news across the nation as the Voice of America trumpeted it around the globe in thirty-four languages. Riveted by these events, reporters gave little thought to the hearings taking place that afternoon in Room 424 of the Senate Office Building, where a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee sat to consider a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States. If passed, it would have declared, “This Nation devoutly recognizes the authority and law of Jesus Christ, Saviour and Ruler of nations through whom are bestowed the blessings of Almighty God.”

1

The campaign for this “Christian amendment” had been under way, in fits and starts, for nearly a century. Like most efforts to add religious elements to American political culture, the idea originated during the Civil War. In 1861, several northern ministers came to believe that the conflict was the result of the godlessness of the Constitution. “We are reaping the effects of its implied atheism,” they warned, and only a direct acknowledgment of Christ's authority could correct such an “atheistic error in our prime conceptions of Government.” These clergymen banded together to create the National Reform Association, an organization that was single-mindedly dedicated to promoting the Christian amendment. It won the support of prominent governors, senators, judges, theologians, college presidents, and professors. “It can never be out of season to explain and enforce mortal dependence on Almighty God,” Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts applauded. Despite his own frequent invocations of faith, however, Lincoln ignored the calls for an amendment, and the effort stalled. Campaigns devoted to the cause appeared sporadically in the decades that followed, but they all failed to find traction.

2

The religious revival of the Eisenhower era, however, gave this long-frustrated movement its best chance yet. In 1954, Republican senator Ralph Flanders of Vermont advanced a new version of the amendment in what would be its latest and greatest campaign. Bald with a short, sandy-colored mustache, wire-rimmed glasses, and a pipe perpetually in hand, the soft-spoken seventy-three-year-old did not look the part of a conservative firebrand. But his convictions ran deep. A former industrialist and head of the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston, Flanders had been an outspoken opponent of the New Deal, which he believed was designed “to establish permanent Federal control over business.” “A fundamentalist on free enterprise,” in the words of a

Saturday Evening Post

profile, Flanders was no different when it came to his faith. Soon after his arrival in Washington, he became a loyal ally of Abraham Vereide, serving as a regular participant in the Senate prayer breakfasts and then chair of his International Council for Christian Leadership. Spurred on by these associations, the senator revived the Christian amendment and advanced it further along the legislative process than ever before. Though overlooked at the time, the 1954 Senate hearings represented a major milestone.

3

Despite such progress, advocates of the Christian amendment still faced an inherently difficult challenge in the Senate. By its very nature, their proposal to change the Constitution forced them to acknowledge that the religious invocation was something new for the document. The founding fathers had felt no need to acknowledge “the law and authority of Jesus Christ,” and neither had subsequent generations of American legislators. Some of the more imaginative advocates of the Christian amendment at the Senate hearings simply waved away this history and argued that leaders such as Washington and Lincoln had supported the idea even if they never acted upon it. For evidence, they repeatedly made reference in their testimony to letters and meetings in which these presidents allegedly had lent support to their cause. At the hearings, the presiding senator kindly offered to have these documents inserted into the official transcript once they were found. But the published record provided a quiet rebuke to such claims, noting that inquiries to the Library of Congress and other authoritative sources showed that the alleged documents did not, in fact, exist.

4

Other supporters of the Christian amendment took a different, if equally imaginative, approach to the issue of original intent. R. E. Robb, a newspaper columnist from South Carolina, compiled a collection of religious invocations from American history, stretching from the Mayflower Compact of 1620 to early twentieth-century America. From them, he testified, “we are warranted in stating categorically that this is in fact basically and fundamentally a Christian nation.” However, Robb admitted, “the Nation itself does not say so. Its official spokesman, its written or enacted Constitution, is silent on the subject.” No matter; there was another “unwritten and vital” constitution whose authority superseded the written one. “The vital, the actual Constitution of this Nation is and always has been Christian, from the first settlers down to the present,” Robb argued. “But the written Constitution, which should accurately reflect the vital Constitution, is sadly lacking in respect to its acknowledgment of Jesus Christ as the Supreme Ruler and His law as the supreme authority of the Nation.” Therefore, it needed to be amended.

5

There was, according to advocates of the Christian amendment, ample evidence of the religious intent of this unwritten constitution, intent that

had been expressed in a variety of official and unofficial ways. The head of the National Reform Association, a Presbyterian minister from Los Angeles named J. Renwick Patterson, presented the Senate with a litany of examples showing how “the spiritual has been woven into the fabric of American life” as part of the “unwritten law of the land.” He singled out the public prayers given in presidential inaugurations and congressional sessions, the chaplains employed by the military and Congress whose salaries were paid with public funds, the tax-exempt status of churches, and the traditional notion of Sunday as a day of rest. “All of these things testify to the place Christianity had had in the past and continues to have in our national life,” Patterson noted. “But when it comes to our Constitution, our fundamental law, there is complete silence regarding God. He isn't even mentioned. There is no recognition, no acknowledgment. In our Constitution there is absolutely nothing to undergird and give legal sanction to the religious practices mentioned above.” Recognizing there was no constitutional authority for these activities, he argued not that these practices should be abandoned but rather that the Constitution should be rewritten to support them.

6