One Hundred Victories (24 page)

Read One Hundred Victories Online

Authors: Linda Robinson

Tags: #Special Ops and the Future of American Warfare

O

D

A

1

32

6

teaches ALP class in Ghazni P

r

o

v

ince

Brandon and Marawara District ALP

Nur

Mohammed and Kunar ALP

Obse

r

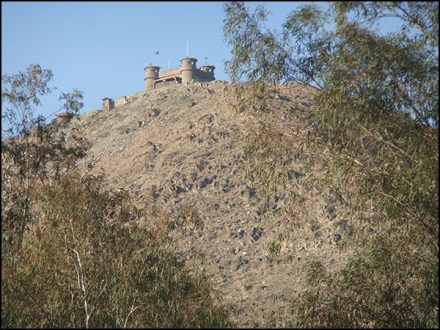

vation Post Shiloh

Ma

j

. Ge

n

. Tony Thomas in graduation ce

r

emony at the

Special Police Training Center in

W

a

r

dak P

r

o

v

ince

CFSOCC-A PHOTO

CHAPTER SEVEN

__________________________________________

ON THE SAME TEAM

…

OR NOT

Kandahar 2012

HUGGER AND SLUGGER

ODA 7233 took the reins from Dan Hayes’s team in Maiwand in 2012. Brad Hansell, the new team leader, was well suited to be a special forces officer, though the idea appalled his father, a navy admiral. Hansell had first gone off the reservation by going to Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training. Though the SEALs had captured the public imagination, they were still a tiny, outsider club in the world of submariners and big ship brass. During the grueling tryout, Hansell had suffered a freak near-drowning accident that rendered him unable to continue. Undaunted, he decided to transfer to the US Army Special Forces Qualification Course in a program that permits sailors to “go green” and don the army’s colors. Hansell loved his father, but wasn’t in thrall to family traditions. He was a restless soul, a thinker, and an incessant talker. He took to the complex puzzle of Maiwand like an iron filing to a magnet.

Hansell and his team sized up the situation in Maiwand. He decided that to move forward they needed to take a step back. He knew Hayes’s team had sweated over two tours to gain recruits for the local police, and that many of the recruits had not come from the immediate Ezabad area. He decided that the program would be stronger if the local police commanders relocated to the villages in which they had been born. Two of the commanders were originally from south of Highway One, and under this plan these two Afghans would go into that critical area to expand the ALP. Southern Maiwand was the most populated zone outside the district center and the major insurgent ratline running into Kandahar City. Hansell had heard that one of the largest absentee landowners in the area, Kala Khan, wanted to return and get his land back into production. If Hansell could cobble together enough Afghan manpower using the ALP commanders, the local Maiwand officials, and the national police, he believed he could make inroads into this key area, particularly with a few assists from the remaining US conventional forces—a watchtower here, a patrol there. If they were lucky, this coalition of Afghans might grow numerous and become strong enough to survive even when the Americans left. Over time, they might just win Maiwand.

Fortunately, Hansell could rely on several solid partners: three or four decent ALP commanders; an Afghan special forces team led by a superb captain, Najibullah; and the excellent Afghan American interpreter who had decided to stay on for a third year, Abdullah Niazi. In Hansell’s plan, the ALP commanders would move in stages to the new areas south of Highway One and recruit volunteer police there. Hansell also wanted to wean the local policemen of some bad habits he had spotted. He took away most of their trucks, except those of the commanders, so the police would stay tethered to their assigned area rather than driving around to meet each other.

The second part of Hansell’s plan was to work hard on the local officials in order to limit such corrupt practices while encouraging their self-interest in expanding security from the district center to the entire district. Maiwand’s police chief, Sultan Mohammed, and its district governor, Saleh Mohammed, had recently been appointed. The new district police chief had taken to using the Afghan Local Police as part of his muscle to persuade the farmers to pay him not to eradicate their poppy crops. Hansell realized what was going on one day when his team was on patrol with an Afghan police commander in his white truck. As they approached, Hansell saw a farmer’s son running across a field with what he thought was an RPG launcher. The team moved in closer and saw that the boy was running away with a pump, which he thought the police were coming to confiscate. When he talked to the farmer, Hansell found out that the district police chief was not only plowing under the poppies of those who did not pay to keep the eradication tractors off their land, but taking their pumps as well.

{95}

Hansell’s predecessor, Dan Hayes, had invested a great deal of time in the previous district governor, Obaidullah Barwari, who had begun to connect with more villagers and stay in the district full time. Hansell believed the new district governor was in cahoots with the new police chief, but he decided not to agitate for their removal. He believed the constant churn of local officials was counterproductive and somewhat pointless, since the incentives for corruption were systemic. The constant game of musical chairs had done little good. Hansell preferred to work on modifying officials’ behavior by degrees. He could not stop the eradication campaign, which alienated the population, or stop local officials from using it to pad their pockets. But he could take steps to keep the ALP from being associated with eradication or the shakedown scheme. If they had no trucks, they could not make the payola visits. Hansell also began meeting frequently with the district police chief and governor to propose ways they could expand the security bubble that currently was confined to Highway One and the district center. Both of these local officials had been assigned embedded US mentors, but those mentors were individual officers who brought no troops, guns, or money as leverage. The Afghan officials naturally were more readily swayed by a special operations team that brought all three to bear.

While Hansell worked on the district governor, meeting with him almost daily, the district police chief became the object of Captain Najibullah’s attentions. The head of the Afghan special forces team ODA 112, Najibullah was a Tajik from Laghman Province near Kabul, not a Pashtun like the Afghans in Maiwand. But he was a devout and deeply principled Muslim who abhorred the rampant corruption that had taken root in Afghan society. “My religion does not allow it. We each have to answer for our behavior, so I do what I can to help,” Najibullah said, explaining his views on the subject. “Things here are bad from the top, and from here we cannot solve everything. People buy positions, and there is a system of bribery. The taker and the payer are both part of it.” He ran herd on the ALP, visiting checkpoints at random and chasing down any guardians reported to have taken bribes. He believed a different approach was needed for the district police chief, however. Najibullah was well aware that the poorly paid police chiefs were unofficially given guidelines for the “take” they were allowed, so he decided he would quietly ask Abdul Raziq, the provincial police chief, if his new subordinate police chief in Maiwand was exceeding the permissible ceiling; if so, Raziq could call him on the carpet.

{96}

Najibullah’s reputation had grown over the past year, and Afghans had responded to his example of moral leadership. In the towns and mosques, he spoke from the heart, and people listened. His high, deeply lined forehead gave him the look of a solemn, sorrowful basset hound. Indeed, he was greatly pained that his countrymen were killing each other. Very often his sincere appeals helped to resolve village disputes, gain ALP recruits, and persuade frightened elders to support an ALP force.

While Hansell and Najibullah focused on shaping the district officials’ behavior, the team whipped the ALP into shape, instilling new discipline. Hansell jokingly referred to himself as the “hugger” and his team sergeant, Chris, as the “slugger.” They were a good match: Chris was caustic and skeptical, balancing Hansell’s energetic optimism, which was not naïveté so much as a determination to find a way through the thicket of Afghan complexities.

“We should have been doing this years ago,” the sunburned team sergeant said as his sergeants strapped on their kits for a foot patrol outside the qalat walls. Like many other veteran special operations sergeants, Chris believed that Village Stability Operations and the Afghan Local Police initiative was the right approach to Afghanistan’s rural insurgency, but that it had been adopted too late to make a difference. He doubted the special operators would be given enough time to ensure that the program was firmly implanted with Afghan ownership before the teams were reduced or pulled out altogether. That did not mean he was going to sit on his heels; he would drive his sergeants every day to move the ball down the field. His sergeant major, Brian Rarey, had put him in charge of the team ahead of his promotion, knowing that the insouciant sergeant would be relentless. His hooch was decorated with a Georgia Bulldogs flag, and the T-shirt he wore inside the qalat was emblazoned with the word “infidel.” Chris was determined to make a difference in the little time they had, but he also saw this as a live training mission to make his men better.

{97}