One and Wonder (34 page)

Authors: Evan Filipek

He felt a tinge of regret that his life was over. Some day he would have liked to have taken a trip somewhere out among the stars. With Thelma.

He started the truck again, and went on around Paxton Hill without looking back again, and down the long grade into Tedrow Valley.

Overhead in the indigo night sky stars shone feebly. In the close confines of the truck cab the high pitched whine of the turbines was lulling, peaceful.

Strange, how peaceful it was when life was over.

Bubble seven loomed in the light from the headlights all too soon.

He glanced at his watch. Zero minus forty-five minutes for the ship. Should he wait? Should he watch it soar into the morning sky, as he and Thelma had watched similar ships before?

No.

That was for the living.

He opened the cab door and stepped out onto the ground. Unconsciously, he had parked where he always parked. The airlock was only a few feet away.

The house was dark. Marvin turned away from it with a sob of torment. He should not have looked at it. He would not look at it again.

He walked out into the darkness toward the pool, the largest and deepest of the three. It would be the one Thelma had chosen.

He reached up and fumbled at the release clamp of his faceplate.

He was calm now. He would open up his faceplate. He would take several deep breaths of the natural atmosphere of Jeffries’ Planet. It was supposed to have an opiate effect that would deaden the pain to come later.

He stilled the panic within him and stiffened his fingers for the final act.

And a sound broke into his consciousness.

The shrill, strident ringing of the phone in his truck.

His first reaction was anger.

Who would be calling at a time like this? To release his faceplate, to breathe in the lethal atmosphere of the planet, to dive into the depths of the dark pool, with the sound of a phone ringing. . .

He made a strange sound, a mixture of a sob and a snort. Then he ran to the truck, stumbling and sprawling halfway there, and picking himself up again and running on.

He jerked the hand mike off its hook and said, “Hello!”

“Is that you, Marvin? My lands, where have you been? I've been trying to reach you for hours!”

It was the voice of his mother-in-law.

“What do you want?” he said dully.

“What do I

want?

” she said. “That's a fine question for you to ask. Don't you even care about your wife? I suppose when you got home and found out she was over here you went into town and got in a card game or something. A lot you care that she's sick, and going to have a baby.”

“What?” Marvin croaked.

“Sure,” Thelma's mother said smugly. “She got sick this afternoon and called me, and we came over there and got her and brought her home with us, and then called the doctor.”

Marvin sagged against the seat.

“What have you been doing?” the voice went on. “Didn't you get her note? I saw her tape it to the inner door of the airlock myself. Maybe it fell off.”

“The baby—” Marvin croaked.

“Two months along, and doing fine. Thelma slipped and fell this noon, and felt dizzy afterwards. It made her afraid . . .”

The words droned on and on, but Marvin was no longer listening.

Thelma had decided to live. She was going to have a baby.

And for the baby, for him, for herself, Thelma had decided to live, to fight for what she held dear, to protect him from the knowledge of what had happened.

“. . . and she can't sleep. If you don't get over here right away, you no good fool . . .”

Dear, wonderful mother-in-law.

“Okay,” Marvin said, laughing and crying. “Okay, I'll come right away. You're right. I'm a fool. I was in town—gambling. I'll be right there. And mother-in-law . . .”

“What is it, you addle-pated son-in-law?”

“Did I ever tell you I love you?”

“Go on, now,” the shrill voice snorted.

The carrier tone ended. She had hung up.

Marvin started to get into the truck, glanced toward the airlock, hesitated, then went over to it. There was no note stuck to the inner door, but after a moment he saw it inside the bubble on the ground, vague in the semi-darkness.

He stepped into the airlock and closed the door. He waited impatiently for the air to clear, then opened the inner door and picked up the envelope. It was grimy with oily dirt where he had stepped on it again and again in his blind torment an eternity ago. He opened it with great tenderness.

“Darling,” it read. “Mama and papa have come to get me. I took sick and didn't want to worry you. Fix your dinner and I will call you or have mama call you later. Love, Thelma.”

Cautiously worded. He could see her as she wrote it. Brave, protecting him, not sure whether the baby would live or die after what had happened . . .

He could do nothing but be equally brave. She would never know that he knew, never know what he had done.

He went back outside.

Suddenly Paxton Hill took on faint detail, and with it the valley around Marvin. One of the twin suns was shooting into sight. Alpha, from its color.

And then came the thunder. It grew deeper, more steady.

Marvin looked up over Paxton Hill into the purpling morning sky. In a moment the ship rose into sight.

A needle shape gleaming in the rays of the suns, riding upward with gathering momentum on a tail of fire.

It grew smaller and smaller, and then he lost it.

Out into the void. Out among the stars. Keeping to its schedule. Connecting the worlds of man, itself a small world, peopled with men who had found their souls—or lost them.

Marvin turned. A few feet away was his truck, the door standing open.

Without hesitation, he went to it and got in.

I was in the US Army in Oklahoma in 1958 when I read this, living off-post with my wife of two years. There's a certain similarity to the setting of this story that perhaps made me relate to it. No, my wife did not get raped, but she did suffer a grueling miscarriage that had her a month in the hospital, as I recall. I remember once I had guard duty during visiting hours, and was able to go to visit her only as the open time ended, and they would not let me see her. She could hear me talking to the impervious nurse in the hall, but I had to go. The machine schedule of the military does not allow for the feelings of real folk. We did go on from there to a better life together. So maybe there were reasons I remembered this story. Rereading it in 2010 I find it taut, compelling, horrible, and excellently done. The insidious logic of the rapist, followed by that of the ship's doctor—both make infernal sense. Crime, punishment, redemption fitted to the crucifix of the situation. Beautiful.

—Piers

DREAMS ARE SACRED

Peter Phillips

September 1948

I remember the opening history of the boy afraid of nightmares, and his father has him practice with a heavy gun, which then joins him in his dreams. I simply loved that; think it is marvelous psychology. I also loved the lucid dreaming, wherein he enters another persons dream and starts changing it about. How good a story it actually is I don't remember, but those two aspects were enough to make me cherish it for life.

—Piers

When I was seven, I read a ghost story and babbled of the consequent nightmare to my father.

“They were coming for me, Pop,” I sobbed. “I couldn't run, and I couldn't stop ‘em, great big things with teeth and claws like the pictures in the book, and I couldn't wake myself up, Pop, I couldn't come awake.”

Pop had a few quiet cuss words for folks who left such things around for a kid to pick up and read; then he took my hand gently in his own great paw and led me into the six-acre pasture.

He was wise, with the canny insight into human motives that the soil gives to a man. He was close to Nature and the hearts and minds of men, for all men ultimately depend on the good earth for sustenance and life.

He sat down on a stump and showed me a big gun. I know now it was a heavy Service Colt .45. To my child eyes, it was enormous. I had seen shotguns and sporting rifles before, but this was to be held in one hand and fired. Gosh, it was heavy. It dragged my thin arm down with its sheer, grim weight when Pop showed me how to hold it.

Pop said: “It's a killer, Pete. There's nothing in the whole wide world or out of it that a slug from Billy here won't stop. It's killed lions and tigers and men. Why, if you aim right, it'll stop a charging elephant. Believe me, son, there's nothing you can meet in dreams that Billy here won't stop. And he'll come into your dreams with you from now on, so there's no call to be scared of anything.”

He drove that deep into my receptive subconscious. At the end of half an hour, my wrist ached abominably from the kick of that Colt. But I'd seen heavy slugs tear through two-inch teakwood and mild steel plating. I'd looked along that barrel, pulled the trigger, felt the recoil rip up my arm and seen the fist-size hole blasted through a sack of wheat.

And that night, I slept with Billy under my pillow. Before I slipped into dreamland, I'd felt again the cool, reassuring butt.

When the Dark Things came again, I was almost glad. I was ready for them. Billy was there, lighter than in my waking hours—or maybe my dream-hand was bigger—but just as powerful. Two of the Dark Things crumpled and fell as Billy roared and kicked, then the others turned and fled.

Then I was chasing them, laughing, and firing from the hip.

Pop was no psychiatrist, but he'd found the perfect antidote to fear—the projection into the subconscious mind of a common-sense concept based on experience.

Twenty years later, the same principle was put into operation scientifically

to save the sanity—and perhaps the life—of Marsham Craswell.

“Surely you've heard of him?” said Stephen Blakiston, a college friend of mine who'd majored in psychiatry.

“Vaguely,” I said. “Science-fiction, fantasy . . . I've read a little. Screwy.”

“Not so. Some good stuff.” Steve waved a hand round the bookshelves of his private office in the new Pentagon Mental Therapy Hospital, New York State. I saw multicoloured magazine backs, row on row of them. “I'm a fan,” he said simply. “Would you call me screwy?”

I backed out of that one. I'm just a sports columnist, but I knew Blakiston was tops in two fields—the psycho stuff and electronic therapy.

Steve said: “Some of it's the old ‘peroo, of course, but the level of writing is generally high and the ideas thought-provoking. For ten years, Marsham has been one of the most prolific and best-loved writers in the game.

“Two years ago, he had a serious illness, didn't give himself time to convalesce properly before he waded into writing again. He tried to reach his previous output, tending more and more towards pure fantasy. Beautiful in parts, sheer rubbish sometimes.

“He forced his imagination to work, set himself a wordage routine. The tension became too great. Something snapped. Now he's here.”

Steve got up, ushered me out of his office. “I'll take you to see him. He won't see you. Because the thing that snapped was his conscious control over his imagination. It went into high gear, and now instead of writing his stories, he's living them—quite literally, for him.

“Far-off worlds, strange creatures, weird adventures—the detailed phantasmagoria of a brilliant mind driving itself into insanity through the sheer complexity of its own invention. He's escaped from the harsh reality of his strained existence into a dream world. But he may make it real enough to kill himself.

“He's the hero of course,” Steve continued, opening the door into a private ward. “But even heroes sometimes die. My fear is that his morbidly overactive imagination working through his subconscious mind will evoke in this dream world in which he is living a situation wherein the hero must die.

“You probably know that the sympathetic magic of witchcraft acts largely through the imagination. A person imagines he is being hexed to death—and dies. If Marsham Craswell imagines that one of his fantastic creations kills the hero—himself—then he just won't wake up again.

“Drugs won't touch him. Listen.”

Steve looked at me across Marsham's bed. I leaned down to hear the mutterings from the writer's bloodless lips.

“. . . . We must search the Plains of Istak for the Diamond. I, Multan, who now have the Sword, will lead thee; for the Snake must die and only in

virtue of the Diamond can his death be encompassed. Come.”

Craswell's right hand, lying limp on the coverlet, twitched. He was beckoning his followers.

“Still the Snake and the Diamond?” asked Steve. “He's been living that dream for two days. We only know what's happening when he speaks in his role of hero. Often it's quite unintelligible. Sometimes a spark of consciousness filters through, and he fights to wake up. It's pretty horrible to watch him squirming and trying to pull himself back into reality. Have you ever tried to pull yourself out of a nightmare and failed?”

It was then that I remembered Billy, the Colt .45. I told Steve about it, back in his office.

He said: “Sure. Your Pop had the right idea. In fact, I'm hoping to save Marsham by an application of the same principle. To do it, I need the cooperation of someone who combines a lively imagination with a severely practical streak, boss-sense—and a sense of humour. Yes—you.”

“Uh? How can I help? I don't even know the guy.”

“You will,” said Steve, and the significant way he said it sent a trickle of ice water down my back. “You're going to get closer to Marsham Craswell than one man has ever been to another.

“I'm going to project you—the essential you, that is, your mind and personality—into Craswell's tortured brain.”

I made pop-eyes, then thumbed at the magazine-lined wall. “Too much of yonder, brother Steve,” I said. “What you need is a drink.”

Steve lit his pipe, draped his long legs over the arm of his chair. “Miracles and witchcraft are out. What I propose to do is basically no more miraculous than the way your Pop put that gun into your dreams so you weren't afraid any more. It's merely more complex scientifically.

“You've heard of the encephalograph? You know it picks up the surface neural currents of the brain, amplifies and records them, showing the degree—or absence—of mental activity. It can't indicate the kind or quality of such activity save in very general terms. By using comparison-graphs and other statistical methods to analyze its data, we can sometimes diagnose incipient insanity, for instance. But that's all—until we started work on it, here at Pentagon.

“We improved the penetration and induction pickup and needled the selectivity until we could probe any known portion of the brain. What we were looking for was a recognizable pattern among the millions of tiny electric currents that go to make up the imagery of thought, so that if the subject thought of something—a number, maybe—the instruments would react accordingly, give a pattern for it that would be repeated every time he thought of that number.

“We failed, of course. The major part of the brain acts as a unity, no

one part being responsible for either simple or complex imagery, but the activity of one portion inducing activity in other portions—with the exception of those parts dealing with automatic impulses. So if we were to get a pattern we should need thousands of pickups—a practical impossibility. It was as if we were trying to divine the pattern of a coloured sweater by putting one tiny stitch of it under a microscope.

“Paradoxically, our machine was too selective. We needed, not a probe, but an all-encompassing field, receptive simultaneously to the multitudinous currents that made up a thought-pattern.

“We found such a field. But we were no further forward. In a sense, we were back where we started from—because to analyze what the field picked up would have entailed the use of thousands of complex instruments. We had amplified thought, but we could not analyze it.

“There was only one single instrument sufficiently sensitive and complex to do that—another human brain.”

I waved for a pause. “I'm home,” I said. “You'd got a thought-reading machine.”

“Much more than that. When we tested it the other day, one of my assistants stepped up the polarity-reversal of the field—that is, the frequency—by accident. I was acting as analyst and the subject was under narcosis.

“Instead of ‘hearing’ the dull incoherencies of his thoughts, I became part of them. I was inside that man's brain. It was a nightmare world. He wasn't a clear thinker. I was aware of my own individuality. . . . When he came round, he went for me bald-headed. Said I'd been trespassing inside his head.

“With Marsham, it'll be a different matter. The dream world of his coma is detailed, as real as he used to make dream worlds to his readers.”

“Hold it,” I said. “Why don't you take a peek?”

Steve Blakiston smiled and gave me a high-voltage shot from his big grey eyes. “Three good reasons: I've soaked in the sort of stuff he dreams up, and there's a danger that I would become identified too closely with him. What he needs is a salutary dose of common sense. You're the man for that, you cynical old whisky-hound.

“Secondly, if my mind gave way under the impress of his imagination, I wouldn't be around to treat myself; and thirdly, when—and if—he comes round, he'll want to kill the man who's been heterodyning his dreams. You can scram. But I want to stay and see the results.”

“Sorting that out, I gather there's a possibility that I shall wake up as a candidate for a bed in the next ward?”

“Not unless you let your mind go under. And you won't. You've got a cast-iron non-gullibility complex. Just fool around in your usual iconoclastic manner. Your own imagination's pretty good, judging by some of your fight reports lately.”

I got up, bowed politely, said: “Thank you, my friend. That reminds me—I'm covering the big fight at the Garden tomorrow night. And I need sleep. It’s late. So long.” Steve unfolded and reached the door ahead of me. “Please,” he said, and argued. He can argue. And I couldn't duck those big eyes of his. And he is—or was—my pal. He said it wouldn't take long—(just like a dentist)—and he smacked down every “if” I thought up.

Ten minutes later, I was lying on a twin bed next to that occupied by a silent, white-faced Marsham Craswell. Steve was leaning over the writer adjusting a chrome-steel bowl like a hair-drier over the man's head. An assistant was fixing me up the same way.

Cables ran from the bowls to a movable arm overhead and thence to a wheeled machine that looked like something from the Whacky Science Section of the World's Fair, A.D. 2,000.

I was bursting with questions, but the only ones that would come out seemed crazily irrelevant.

“What do I say to this guy? ‘Good morning, and how are all your little complexes today?’ Do I introduce myself?”

“Just say you're Pete Parnell, and play it off the cuff,” said Steve. “You'll see what I mean when you get there.”

Get there. That hit me—the idea of making a journey into some nut's nut. My stomach drew itself up to softball size.

“What's the proper dress for a visit like this? Formal?” I asked. At least, I think I said that. It didn't sound like my voice.

“Wear what you like.”

“Uh-huh. And how do I know when to draw my visit to a close?”

Steve came round to my side. “If you haven't snapped Craswell out of it within an hour, I'll turn off the current.” He stepped back to the machine. “Happy dreams.” I groaned.

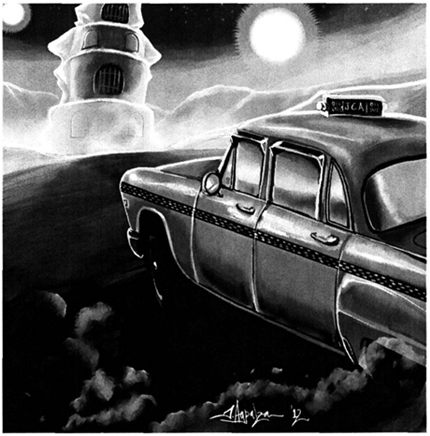

It was hot. Two high summers rolled into one. No, two suns, blood-red, stark in a brazen sky. Should be cool underfoot—soft green turf, pool table smooth to the far horizon. But it wasn't grass. Dust. Burning green dust—

The gladiator stood ten feet away, eyes glaring in disbelief. All of six-four high, great bronzed arms and legs, knotted muscles, a long shining sword in his right hand. But his face was unmistakable. This was where I took a good hold of myself. I wanted to giggle.