One and Wonder (16 page)

Authors: Evan Filipek

Somewhere a baby cried.

Anderson threw his forearm over his eyes.

Someone went “Shh!” but the baby went right on crying.

Anderson said, “Who's there?”

“Just me, darling.”

He breathed deeply, twice, and then whispered, “Louise?”

“Of course.

Shh,

Jeannie!”

“Jeannie's with you, Louise? She's all right? You're—all right?”

“Come and see,” the sweet voice chuckled.

Captain Anderson dove into the blackness aft. It closed over him silently and completely.

On the table stood an ivory figurine, a quarter-keg of beer, a thorny cross, and a heart. It wasn't a physiological specimen; rather it was the archetype of the most sentimental of symbols; the balanced, cushiony, brilliant-red valentine heart. Through it was a golden arrow, and on it lay cut flowers: lilies, white roses, and forget-me-nots. The heart pulsed strongly; and though it pumped no blood, at least it showed that it was alive, which made it, perhaps, a better thing than it looked at first glance.

Now it was very quiet in the ship, and very dark.

VII

... We are about to land. The planet is green and blue below us, and the long trip is over. . . . It looks as if it might be a pleasant place to live . . .

A fragment of Old Testament verse has been running through my mind—from Ecclesiastes, I think. I don't remember it verbatim, but it's something like this:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven: A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, anda time to cast away; A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted.

For me, anyway, I feel that the time has come. Perhaps it is not to die, but something else, less final or more terrible.

In any case, you will remember, I know, what we decided long ago—that a man owes one of two things to his planet, to his race: posterity, or himself. I could

not contribute the first—it is only proper that I should offer the second and not shrink if it is accepted . . .

—From a letter by Peter Hoskins to his wife.

In the quiet and the dark, Hoskins moved.

“Checkmate,” he said.

He rose from his chair and crossed the cabin. Ignoring what was on the table, he opened a drawer under the parts cabinet and took out a steel rule. From a book rack he lifted down a heavy manual. He sat on the end of the couch with the manual on his knees and leafed through it, smoothing it open at a page of physical measurements. He glanced at the floor, across it to the black curtain, back to the one exposed bulkhead. He grunted, put the book down, and carried his tape to the steel wall. He anchored one end of it there by flipping the paramagnetic control on the tape case, and pulled the tape across the room. At the blackness he took a reading, made a mark.

Then he took a fore-and-aft measurement from a point opposite the forward end of the table to one opposite the after end of the bunk. Working carefully, he knelt and constructed a perpendicular to this line. He put the tape down for the third time, arriving again at the outboard wall of darkness. He stood regarding it thoughtfully, and then unhesitatingly plunged his arm into it. He fumbled for a moment, moving his hand around in a circle, pressing forward, trying again. Suddenly there was a click, a faint hum. He stepped back.

Something huge shouldered out of the dark. It pressed forward toward him, passed him, stopped moving.

It was the port.

Hoskins wiped sweat away from his upper lip and stood blinking into the airlock until the outer port opened as well. Warm afternoon sunlight and a soft, fresh breeze poured in. In the wind was birdsong and the smell of growing things. Hoskins gazed into it, his mild eyes misty. Then he turned back to the cabin.

The darkness was gone. Ives was sprawled on the after couch, apparently unconscious. Johnny was smiling in his sleep. The Captain was snoring stertorously, and Paresi was curled up like a cat on the floor. The sunlight streamed in through the forward viewports. The manual wheel gleamed on the bulkhead, unbroken.

Hoskins looked at the sleeping crew and shook his head, half-smiling. Then he stepped to the control console and lifted a microphone from its hook. He began to speak softly into it in his gentle, unimpressive voice. He said:

“Reality is what it is, and not what it seems to be. What it seems to be is an individual matter, and even in the individual it varies constantly. If that's a truism, it’s still the truth, as true as the fact that this ship cannot fail. The

course of events after our landing would have been profoundly different if we had unanimously accepted the thing we knew to be true. But none of us need feel guilty on that score. We are not conditioned to deny the evidence of our senses.

“What the natives of this planet have done is, at base, simple and straightforward. They had to know if the race who built this ship could do so because they were psychologically sound (and therefore capable of reasoning out the building process, among many, many other things) or whether we were merely mechanically apt. To find this out, they tested us. They tested us the way we test steel—to find out its breaking point. And while they were playing a game for our sanity, I played a game for our lives. I could not share it with any of you because it was a game only I, of us all, have experience in. Paresi was right to a certain degree when he said I had retreated into abstraction—the abstraction of chess. He was wrong, though, when he concluded I had been driven to it. You can be quite sure that I did it by choice. It was simply a matter of translating the contactual evidence into an equivalent idea-system.

“I learned very rapidly that when they play a game, they abide by the rules. I know the rules of chess, but I did not know the rules of their game. They did not give me their rules. They simply permitted me to convey mine to them.

“I learned a little more slowly that, though their power to reach our minds is unheard-of in any of the seven galaxies we know about, it still cannot take and use any but the ideas in the fore-front of our consciousness. In other words, chess was a possibility. They could be forced to take a sacrificed piece, as well as being forced to lose one of their own. They extrapolate a sequence beautifully—but they can be out-thought. So much for that: I beat them at chess. And by confining my efforts to the chessboard, where I knew the rules and where they respected them, I was able to keep what we call sanity. Where you were disturbed because the port disappeared, I was not disturbed because the disappearance was not chess.

“You're wondering, of course, how they did what they did to us. I don't know. But I can tell you what they did. They empathize—that is, see through our eyes, feel with our fingertips—so that they perceive what we do. Second, they can control those perceptions; hang on a distortion circuit, as Ives would put it, between the sense organ and the brain. For example, you'll find all our fingerprints all around the port control, where, one after the other, we punched the wall and thought we were punching the button.

“You're wondering, too, what I did to break their hold on us. Well, I simply believed what I knew to be the truth; that the ship is unharmed and unchanged. I measured it with a steel tape and it was so. Why didn't they force me to misread the tape? They would have, if I'd done that measuring

first. At the start they were in the business of turning every piece of pragmatic evidence into an outright lie. But I outlasted the test. When they'd finished with their whole arsenal of sensory lies, they still hadn't broken me. They then turned me loose, like a rat in a maze, to see if I could find the way out. And again they abided by their rules. They didn't change the maze when at last I attacked it.

“Let me rephrase what I've done; I feel uncomfortable cast as a superman. We five pedestrians faced some heavy traffic on a surface road. You four tried nobly to cross—deaf and blind-folded. You were all casualties. I was not; and it wasn't because I am stronger or wiser than you, but only because I stayed on the sidewalk and waited for the light to change. . . .

“So we won. Now. . .”

Hoskins paused to wet his lips. He looked at his shipmates, each in turn, each for a long, reflective moment. Again his gentle face showed the half-smile, the small shake of the head. He lifted the mike.

“... In my chess game I offered them a minor piece in order to achieve a victory, and they accepted. My interpretation is that they want

me

for further tests. This need not concern you on either of the scores which occur to you as you hear this. First: The choice is my own. It is not a difficult one to make. As Paresi once pointed out, I have a high idealistic quotient. Second: I am, after all, a very minor piece and the game is a great one. I am convinced that there is no test to which they can now subject me, and break me, that any one of you cannot pass.

“But you must in no case come tearing after

me in

a wild and thoughtless rescue attempt. I neither want that nor need it. And do not judge the natives severely; we are in no position to do so. I am certain now that whether I come back or not, these people will make a valuable addition to the galactic community.

“Good luck, in any case. If the tests shouldn't prove too arduous, I'll see you again. If not, my only regret is that I shall break up what has turned out to be, after all, a very effective team. If this happens, tell my wife the usual things and deliver to her a letter you will find among my papers. She was long ago reconciled to eventualities.

“Johnny . . . the natives will fix your lighter. . .

“Good luck, good-bye.”

Hoskins hung up the microphone. He took a stylus and wrote a line:

“Hear my recording. Pete. “

And then, bareheaded and unarmed, he stepped through the port, out into the golden sunshine. Outside he stopped, and for a moment touched his cheek to the flawless surface of the hull.

He walked down into the valley.

Rereading this story over half a century later, I was dismayed at first by the fast introduction of five different characters, making it hard for me to keep them straight. I don't remember being bothered by this when I first read it, so it may be that at age 76 my ability to spot-remember new names was not what it was at age 18. I'm not sure how else it could have been done, short of having a sidebar listing the names and offices for easy reference. The viewpoint perplexed me; there seems to be none, not even omniscient, just a narrative of who said and did what. Had I first encountered this story today the beginning of it would not have impressed me. Then came the message: “Men of Earth! Welcome to our planet,” and the game was on. Things would not work. I have been frustrated innumerable times by false error messages locking into the computer, requiring a complete resetting and possible loss of material to clear; I think I'd have reacted much as the crewmen did, had I been one of them. I remembered little of the detail from before, just the overall thrust and details like sweeping away the chessboard. So what do I think of it now? It's a psychological tour de force as each member of the crew is stressed to his breaking point. Except one, who had seemed to have cracked early when he locked onto his chess game. But as it turned out, he was using a game whose rules he knew to relate to the one whose rules he didn't know. I think of it as being like the mechanism to trisect a line: create a trisected line, then draw parallels to the original line, and they will trisect it. Genius, in this situation, where they could not trust their senses. How are the folk of a foreign planet to judge an intruding machine with aggressive creatures aboard? This is an answer. Does it remain my all-time favorite? I don't know, but certainly it's one great story.

—Piers

VENGEANCE FOR NIKOLAI

Walter M. Miller, Jr.

1957

In 1957 a new science fiction magazine appeared, VENTURE, so naturally I gave it a try. The first issue had Sturgeon’s “The Girl Had Guts,” and the second issue this one. I don’t remember what else was in it, but this savage story thrilled me. It was told from an original viewpoint. In those days the cold war was in full force, and all things Soviet were public anathema, so it surely took courage for an author to make a Russian assassin the hero. And the way she killed him—I had never imagined that before. I also learned a new word, “demesnes,” one I have subsequently used often enough in my own fiction. The story had verisimilitude—another word I learned from a science fiction story. That is, it seemed that this was the way future war would be; it was believable in its ugliness. My sympathy was with the girl throughout, regardless of her mission. The purpose of any story is to entertain and sometimes broaden the reader’s perspective. This did that for me. It was in my fond memory my #2 favorite story.

—Piers

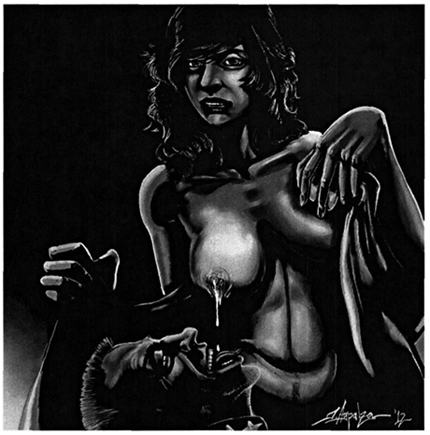

The distant thunder of the artillery was only faintly audible in the dugout. The girl sat quietly picking at her hands while the colonel spoke. She was only a slip of a girl, all breast and eyes, but there was an intensity about her that made her unmistakably beautiful, and the colonel kept glancing at her sidelong as if his eyes refused to share the impersonal manner of his speech. The light of a single bare bulb glistened in her dark hair and made dark shadows under deep jade eyes already shadowed by weeping. She was listening intently or not at all. She had just lost her child.

“They will not kill you

, grazhdanka,

if you can get safely past the lines,” said the colonel. He paced slowly in the dugout, his boot heels clicking pleasantly on the concrete while he sucked at a long cigarette holder and milked his thumbs behind his back in solemn thought. “These Americans, you have heard about their women? No, they will not kill you, unless by accident in passing the lines. They may do other things to you—forgive me!—it is war.” He stopped pacing, straddled her shadow, and looked down at her with paternal pity. “Come, you have said nothing, nothing at all. I feel like a swine for asking it of you, but there is no other hope of beating back this attack. And I am ordered to ask you. Do you understand?”

She looked up. Light filled her eyes and danced in them with the moist glittering of a fresh grief, already an ancient grief, old as Man. “They killed my Nikolai,” she said softly. “Why do you speak to me so? What can it mean? The bombardment—I know nothing—I cannot think of it. Why do you torment me?”

The colonel betrayed no impatience with her, although he had gone over it twice before. “This morning you tried to leap off the bridge. It is such a shame to die without purpose,

dushka.

I offer you a purpose. Do you love the Fatherland?”

“I am not a Party member,

Tovarish Polkovnik.”

“I did not ask if you love the Party, my dear. However, you should say

’parties,‘

now that we are tolerating those accursed Menshevist deviationists again. Bah!

They

even name members of the

Gorodskoi

Soviets these days. We are becoming a two party republic. How sickening! Where are the old warrior Bolsheviks? It makes one weep. . . . But that is not the question. I asked if you love the Fatherland.” She gave a hesitant nod.

“Then think of the Fatherland, think of vengeance for Nikolai. Would you trade your life for that? I know you would. You were ready to fling it away.”

She stirred a little; her mind seemed to re-enter the room. “This Ami

Gyenyeral.

Why do you wish him dead?”

“He is the genius behind this assault, my child. Who would have thought the Americans would have chosen such an unlikely place for an invasion? And the manner of it! They parachuted an army ninety miles inland,

instead

of assaulting the fortified coastline. He committed half a million troops to deliberate encirclement. Do you understand what this means? If they had been unable to drive to the coast, they would have been cut off, and the war would very likely be over. With

our

victory. As it was, the coast defenders panicked. The airborne army swept to the sea to capture their beachhead without need of a landing by sea, and now there are two million enemy troops on our soil, and we are in full retreat.

Flight

is a better word. General Rufus MacAmsward gambled his country's entire future on one operation, and he won. If he had lost, they would likely have shot him. Such a man is necessarily mad. A megalomaniac, an evil genius. Oh, I admire him very much! He reminds me of one of their earlier generals, thirty years ago. But that was before their Fascism, before their Blue Shirts.”

“And if he is killed?”

The colonel sighed. He seemed to listen for a time to the distant shell-fire. “We are all a little superstitious in wartime,” he said at last. “Perhaps we attach too much significance to this one man. But they have no other generals like

him.

He will be replaced by a competent man. We would rather fight competent men than fight an unpredictable devil. He keeps his own counsels, that is so. We know he does not rely heavily upon his staff. His will rules the operation. He accepts intelligence but not advice. If he is struck dead—well, we shall see.”

“And I

am

to kill him. It seems unthinkable. How do you know I can?”

The colonel waved a sheaf of papers. “Only a woman can get to him. We have his character clearly defined. Here is his psychoanalytic biography. We have photo-sats of medical records taken from Washington. We have interviews with his ex-wife and his mother. Our psychologists have studied every inch of him. Here, I'll read you—but no, it is very dry, full of psychiatric jargon. I'll boil it down.

“MacAmsward is a champion of the purity of womanhood, and yet he is a vile old lecher. He is at once a baby and an old man. He will kneel and kiss your hand—yes, really. He is a worshiper of womanhood. He will court you, pay you homage, and then expect you to—forgive me—to take him to bed. He could not possibly make advances on you uninvited, but he expects you—as a goddess rewarding a worshiper—to make advances on

him.

He will be your abject servant, but with courtly dignity. His life is full of breast symbols. He clucks in his sleep. He has visited every volcano in the world. He collects anatomical photographs; his women have all been bosomy brunettes. He is still in what the Freudians call the oral stage of emotional development—emotionally a two-year-old. I know Freud is bad

politics, but for the Ami, it is sometimes so.”

The colonel stopped. There was a sudden tremor in the earth. The colonel lurched, lost his balance. The floor heaved him against the wall. The girl sat still, hands in her lap, face very white. The air shock followed the earth shock, but the thunder clap was muted by six feet of concrete and steel. The ceiling leaked dust.

“Tactical A-missile,” the colonel hissed. “Another of them! If they keep it up, they'll drive us to use Lucifer. This is a mad dog war. Neither side uses the H-bomb, but in the end one side or the other will have to use it. If the Kremlin sees certain defeat, we'll use it. So would Washington. If you're being murdered, you might as well take your killer with you if you can. Bah! It is a madness. I, Porphiry Grigoryevich, am as mad as the rest. Listen to me, Marya Dmitriyevna, I met you an hour ago, and now I am madly in love with you, do you hear? Look at you! Only a day after a bomb fragment dashed the life out of your baby, your bosom still swelled with unclaimed milk and dumb grief, and yet I dare stand here and say I am in love with you, and in another breath ask you to go and kill yourself by killing an Ami general! Ah, ah! What insane apes we are! Forget the Ami general. Let us both desert, let us run away to Africa together, to Africa where apes are simpler. There! I've made you cry. What a brute is Porphiry, what a brute!”

The girl breathed in gasps. “Please,

Tovarish Polkovnik!

Please say nothing more! I will go and do what you ask, if it is possible.”

“I only ask it,

dushka,

I cannot command it. I advise you to refuse.”

“I will go and kill him. Tell me how! Is there a plan? There must be a plan. How shall I pass the lines? How shall I get to him? What is the weapon? How can I kill him?”

“The weapon, you mean? The medical officer will explain that. Of course, you'll be too thoroughly searched to get even a stickpin past the lines. They often use fluoroscopy, so you couldn't even swallow a weapon and get it past them. But there's a way, there's a way—I'll let the

vrach

explain it. I can only tell you how to get taken to MacAmsward after your capture. As for the rest of it, you will be directed by post-hypnotic suggestion. Tell me, you were an officer in the Woman's Defense Corps, the home guard, were you not?”

“Yes, but when Nikki was born, they asked for my resignation.”

“Yes, of course, but the enemy needn't find out you're inactive. You have your uniform still? . . . Good! Wear it. Your former company is in action right now. You will join them briefly?”

“And be captured?”

“Yes. Bring nothing but your ID tags. We shall supply the rest. You will carry in your pocket a certain memorandum addressed to all home guard unit commanders. It is in a code the Ami have already broken. It contains

the phrase: ‘Tactical bacteriological weapons immediately in use.’ Nothing else of any importance. It is enough. It will drive them frantic. They will question you. Since you know nothing, they can torture nothing out of you.

“In another pocket, you will be carrying a book of love poetry. Tucked in the book will be a photograph of General Rufus MacAmsward, plus two or three religious ikons. Their Intelligence will

certainly

send the memorandum to MacAmsward; both sides are that nervous about germ weapons. It is most probable that they will send him the book and the picture—for reasons both humorous and practical. The rest will take care of itself. MacAmsward is all ego. Do you understand?”

She nodded. Porphiry Grigoryevich reached for the phone.

“Now I am going to call the surgeon,” he said. “He will give you several injections. Eventually, the injections will be fatal, but for some weeks, you will feel nothing from them. Post-hypnotic urges will direct you. If your plan works, you will not kill MacAmsward in the literal sense. If the plan fails, you'll kill him another way if you can. You were an actress, I believe?”

“For a time. I never got to the Bolshoi.”

“But excellent! His mother was an actress. You speak English. You are beautiful, and full of grief. It is enough. You are the one. But do you really love the Fatherland enough to carry it out?”

Her eyes burned. “I hate the killers of my son!” she whispered.

The colonel cleared his throat. “Yes, of course. Very well, Marya Dmitriyevna, it is death I am giving you. But you will be sung in our legends for a thousand years. And by the way—” He cocked his head and looked at her oddly. “I believe I really do love you,

dushka. “

With that, he picked up the phone.

Strange exhilaration surged within her as she crawled through the brush along the crest of the flood embankment, crawled hastily, panting and perspiring under a smoky sun in a dusty sky while Ami fighters strafed the opposite bank of the river where her company was retreating. The last of the Russ troops had crossed, or were killed in crossing. The terrain along the bank where she crawled was now the enemy's. There was no lull in the din of battle, and the ugly belching of artillery mingled with the sound of the planes to batter the senses with a merciless avalanche of noise; but the Ami infantry and mechanized divisions had paused for regrouping at the river. It would be a smart business for the Americans to plunge on across the river at once before the Russians could recognize and prepare to defend it, but perhaps they could not. The assault had carried the Ami forces four hundred miles inland, and it had to stop somewhere and wait for the supply lines to catch up. Marya's guess—and it was the educated guess of a former officer—was that the Ami would bridge the river immediately under

air cover and send mechanized killer-strikes across to harass the retreating Russ without involving infantry in an attempt to occupy territory beyond the river.

She fell flat and hugged the earth as machine-gun fire traversed the ridge. A tracer hit rock a yard from her head, spraying her with dust, and sang like a snapped wire as it shot off to the south. The spray of bullets traveled on along the ridge. She moved ahead again.

The danger was unreal. It was all part of an explosive symphony. She had the manna. She could not be harmed. Nothing but vengeance lay ahead. She had only to crawl on.

Was it the drug that made her think like that? Was there a euphoric mixed in the injections? She had felt nothing like this during the raids. During the raids there was only fear, and the struggle to remember whether she had left the teapot boiling while the bombs blew off.