Once (3 page)

Authors: Morris Gleitzman

Tags: #Young Adult Fiction, #Historical, #Holocaust, #Religious, #Jewish, #Juvenile Fiction

“Um…,” I say.

“I remember now, Felek,” says Mother Minka. “I asked you to come down and collect your notebook. Now you’ve got it, go back upstairs.”

I stare at her, confused.

Why is she calling me Felek? My name’s Felix.

I don’t wait to try and work it out. I head for the door. The librarian is still scowling at me. Mother Minka is still looking very stern. But also, I see as I brush past her, very worried.

Suddenly she grabs my ear.

“I’ll take you myself,” she says.

She drags me along the corridor, but instead of dragging me upstairs, she pulls the kitchen door open and bundles me inside.

I’ve only been in the kitchen a few times before, to trim mold off bread as a punishment for talking in class, and I’d forgotten what a great soupy smell there is in here.

I don’t have a chance to enjoy it today.

Mother Minka has shut the door behind us and is crouching down so her face is level with mine. She’s never done that before, ever.

Why is she acting so strangely?

Maybe whoever trimmed her bread for dinner last night didn’t do a very good job. Dodie says eating bread mold can affect your brain.

“This must be terrible for you,” she says. “I wish you hadn’t seen what they’re doing out there. I didn’t think those brutes would bother coming all the way up here, but it seems they go everywhere sooner or later.”

“Librarians?” I say, confused.

“Nazis,” says Mother Minka. “How they knew I had Jewish books here I’ve no idea. But don’t worry. They don’t suspect you’re Jewish.”

I stare at her.

These Nazis or whatever they’re called are going around burning Jewish books?

Suddenly I feel a stab of fear for Mum and Dad.

“When my parents sent the carrot,” I say, “did they mention when they’d actually be getting here?”

Mother Minka looks at me sadly for a long time. Poor thing. Forgetting my name was bad enough. Now she’s forgotten what Mum and Dad told her as well.

“Felix,” she says, “your parents didn’t send the carrot.”

I desperately try to see signs of bread-mold madness in her eyes. It must be that. Mother Minka wouldn’t lie because if she did she’d have to confess it to Father Ludwik.

“Sister Elwira put the carrot in your soup,” says Mother Minka. “She did it because she…well, the truth is she felt sorry for you.”

Suddenly I feel like I’m the one with bread-mold madness burning inside me.

“That’s not true,” I shout. “My mum and dad sent that carrot as a sign.”

Mother Minka doesn’t get angry, or violent. She just puts her big hand gently on my arm.

“No, Felix,” she says. “They didn’t.”

Panic is swamping me. I try to pull my arm away. She holds it tight.

“Try and be brave,” she says.

I can’t be brave. All I can think about is one awful thing.

Mum and Dad aren’t coming.

“We can only pray,” says Mother Minka. “We can only trust that God and Jesus and the Blessed Mary and our holy father in Rome will keep everyone safe.”

I can hardly breathe.

Suddenly I realize this is even worse than I thought.

“And Adolf Hitler?” I whisper. “Father Ludwik says Adolf Hitler keeps us safe too.”

Mother Minka doesn’t answer, just presses her lips together and closes her eyes. I’m glad she does because it means she can’t see what I’m thinking.

There’s a gang of thugs going around the country burning Jewish books. Mum and Dad, wherever in Europe they are, probably don’t even know their books are in danger.

I have to try and find Mum and Dad and tell them what’s going on.

But first I must get to the shop and hide the books.

Dodie opens his eyes wide even though we’re kneeling in chapel and meant to be praying.

“Jewish?” he says. “You?”

I nod.

“What’s Jewish?” he says.

It’s too risky to try to explain all the history and the geography of it. I’ve already spent most of this prayer telling Dodie about Mum and Dad and why I have to leave. Father Ludwik has just turned around, and he’s got eyes like that saint with the really good eyesight.

“Jewish is like Catholic only different,” I whisper.

Dodie thinks about this. He gives me a sad look.

“I’ll miss you,” he whispers.

“Same here,” I say.

I give him the carrot. It’s fluffy and a bit squashed, but I want him to have it because he hasn’t got a mum and dad to give him one.

Dodie can’t believe it.

“Is this a whole carrot?” he says.

“When I come back to visit,” I say, “I’ll bring more. And turnips.”

I wait till everyone’s gone into breakfast, then I creep up to the dormitory to pack.

I pull my suitcase from under my bed and empty it out. The clothes I was wearing when I arrived here are much too small for me now, so I stuff them back into the suitcase and slide it back under the bed. Best to travel light.

All that’s left are the books I brought from home and the letters Mum and Dad wrote to me before the postal service started to have problems.

I put the books on Dodie’s bed. They’re my favorite books in the whole world, the William books by Richmal Crompton that Mum and Dad used to read to me. William was their favorite when they were kids too, even though Richmal Crompton isn’t a Jewish writer, she’s English. I used to think Mum and Dad were translating the words into Polish themselves, but then I found out somebody had already done it.

I’ve always loved the William stories. He always tries to do good things, and no matter how much mess and damage he causes, no matter how naughty he ends up being, his mum and dad never leave him.

Dodie knows I’d never give these books away forever. When he finds them on his bed he’ll know I’ll be back for a visit.

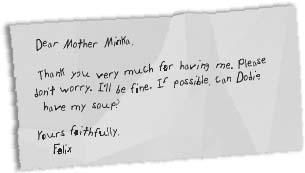

I pick up my notebook, tear out a clean page, and write a note.

I put my notebook and pencil and letters inside my shirt.

I’m ready.

I peer out the window. The sun is shining brightly. The Nazis have gone. The courtyard is empty except for a pile of smoking ash and a few charred books.

If I’m quick, I can be out of here before everyone finishes breakfast.

I hurry past the other beds, trying not to feel sad about going, and I’m just about to leave the dorm when somebody steps in through the door and blocks my way.

Jankiel.

“Don’t go,” he says.

I stare at him, my thoughts racing. He must have overheard me telling Dodie about leaving. I remember him asking me about making up stories. He must want me to stay and teach him how to make up stories himself.

I can see he’s desperate, the poor kid. Desperate for something to keep the torture squad’s mind off stuffing him down the toilet.

“You know how to make up stories already,” I say.

“What?” he says.

“Stories,” I say. “Half of Saint Jadwiga dorm’s still blubbing over that story you told them while we were queuing for chapel. About all the different ways you tried to get the dead horse off your parents. Cranes. Tugboats. Balloons. That was brilliant. Some of those girls were looking at you in that weepy adoring way nuns look at Jesus.”

“Really?” says Jankiel, sounding pleased.

“Here,” I say, pulling out my notebook. “Here’s what a story looks like written down. Practice as much as you can and you’ll be fine.”

I tear out a page for him. It’s the story where Mum and Dad hack their way through the jungle to a remote African village and help mend some bookshelves.

“Thanks,” says Jankiel.

He looks so confused and grateful I know he won’t mind if I excuse myself and hurry off.

I’m wrong. As I move past him he suddenly looks desperate again and grabs my arm.

Oh, no. If I try and fight him to get away and he starts yelling, every nun for a hundred miles around will come running.

“Don’t go,” he says. “It’s too dangerous.”

I know what he means. If the nuns see me sneaking out I’ll be history, but I’ve got to risk it.

I pull myself out of Jankiel’s grip.

“There are Nazis everywhere,” he says.

“I know,” I say. “That’s why I have to go.”

Jankiel screws up his face and stares at the floor.

“Look,” he says, “I can’t tell you what the Nazis are doing because Mother Minka made me swear on the Bible that I wouldn’t tell anyone. She doesn’t want everyone upset and worried.”

“Thanks,” I say. “But I know what they’re doing. They’re burning books.”

Jankiel looks like he’s having a huge struggle inside himself. Finally he gives a big sigh and his shoulders slump.

“Just don’t go,” he says. “You’ll regret it if you do. Really regret it.”

For the first time I feel a jab of fear.

I squash it.

“Thanks for the warning,” I say. “That vivid imagination of yours is going to be really helpful when you need to make up more stories.”

He doesn’t say anything. He can see I’m going.

I go.

I escaped from an orphanage in the mountains and I didn’t have to do any of the things you do in escape stories.

I escaped from an orphanage in the mountains and I didn’t have to do any of the things you do in escape stories.

Dig a tunnel.

Disguise myself as a priest.

Make a rope from nun robes knotted together.

I just walked out through the main gate.

I slither down the mountainside through the cool green forest, feeling very grateful to God, Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Pope, and Adolf Hitler. Grateful that after the Nazis left this morning, the nuns didn’t lock the gate. Grateful that this mountainside is covered in pine needles rather than tangled undergrowth and thorns.

Mother Minka took us out on an excursion once, to look for blackberries. Dodie got tangled in thorns. He cried for his mum, but she wasn’t there.

Only me.

Stop it.

Stop feeling sad about him.

People who feel sad make careless mistakes and get caught. They trip over tree roots and slide down mountains on their heads and break their glasses and the nuns hear them swearing.

I slither to a halt and listen carefully, trying to hear if Father Ludwik and his horse are on the mountain road looking for me.

All I can hear is birds and insects and the trickle of a stream.

I push my glasses more firmly onto my face.

Mum and Dad are the ones who need me now.

I think about getting to the shop and hiding our books and finding a train ticket receipt that tells me where Mum and Dad are and which train I have to catch to find them.

I think about how wonderful it’ll be when we’re all together again.

I have a drink from the stream and head down the mountain through beams of golden sunlight.

You know how when you haven’t had a cake for three years and eight months and you see a cake shop and you start tasting the cakes even before they’re in your mouth? Soft boiled buns oozing with icing. Sticky pastries dripping with chocolate and bursting with cream. Jam tarts.

I’m doing that now.

I can smell the almond biscuits too, even though I’m crouching in a pigpen and there’s a very smelly pig sticking its snout in my ear.

Over there, across that field, is Father Ludwik’s village. It must be. It was the only village I could see as I was coming down into the valley. One of those buildings must definitely be a cake shop. But I can’t go any closer, not wearing these orphanage clothes. Father Ludwik has probably put the word around that an escaped orphan is on the loose. Plus Nazi book burners could be in the general store buying matches.

The pig is looking at me with sad droopy eyes.

I know how it feels.

“Cheer up,” I say to the pig. “I don’t want to waste time in that village anyway.”

I need to get to my hometown. And the good news is I know it’s on a river that flows near here. When Mum and Dad drove me to the orphanage in the bookshop cart, we traveled next to the river almost the whole way to the mountains.

The pig cheers up.

It snuffles the sore patches on my feet.

“You’re right,” I say. “These orphanage shoes hurt a lot. I need to get some proper shoes from somewhere, ones that aren’t made from wood, and some proper clothes, and directions to the river.”

The pig frowns and I can see it’s trying to remember where the river is.