On My Way to Samarkand: Memoirs of a Travelling Writer (20 page)

Read On My Way to Samarkand: Memoirs of a Travelling Writer Online

Authors: Garry Douglas Kilworth

Finally I went for an interview with Cable and Wireless, the international telecommunications company that operated in almost fifty countries, mostly ex-colonies of Britain. C&W was an old-fashioned kind of firm, a civil service type company whose only shareholder was the Treasury. It was very like the RAF, with cousins and uncles working side-by-side, and thousands of overseas employees.

I was interviewed by the man who would be my immediate boss, Ian Bowles, who ran the International Telephone Section of the Traffic Department. (Telephone traffic, not road traffic.) He explained that C&W were like British Telecom. They didn’t make or sell things, they provided a service. They owned and operated telephone, telegraph and teleprinter networks abroad.

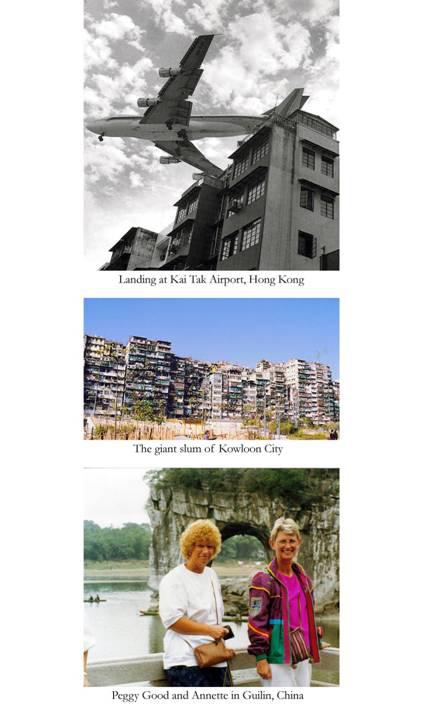

‘For example, Hong Kong Telco.’

‘Yes, I did know that – I’ve been posted to such places in the past,’ I told Ian.

‘Have you ever worked with erlangs?’ he asked me.

I had no idea what ‘erlangs’ were, but he explained patiently that they were a measurement of telephone usage and that the erlang formula was used to calculate the number of circuits needed for an international or indeed national telephone route.

‘Nope,’ I replied, crestfallen.

‘Oh well, never mind. How about Strowger?’

‘Automatic telephone exchange,’ I replied, ‘invented by the American undertaker, Almon Brown Strowger, who was convinced that the telephone operator in his town was giving a rival his business by redirecting calls from potential customers. The telephone operator’s husband was also an undertaker and was therefore without doubt given preferential treatment by his wife. We’ve been using Strowger exchanges since the late 1800s, haven’t we?’

Ian smiled. ‘Well, you’ve got that off pat, haven’t you?’

‘It’s a good story,’ I replied. ‘I like stories.’

The subject had also formed part of my telegraphist training in the RAF.

‘We’ll soon teach you all about erlang formulas – and a lot of other stuff. I’m impressed you went out and got an HND at your age. Shows initiative and a willingness to learn. You’ll come into the company as a Grade 4 Executive. That’s where our bright youngsters straight out of uni and school start, but I’m sure you’ll surge ahead, with all your previous experience in telecoms. All right?’

The salary, at £2,600, was over twice that offered by GCHQ.

I took the job.

~

I went back to Strike Command and was demobbed within a few days. I had grown a beard which upset the Station Warrant Officer. I also found I had gone one day over the rental week and they wanted rent on the married quarter for my final single night in the married quarter. I had served nearly eighteen years in the RAF and they were chasing me for one night’s rent amounting to two pounds! It revealed a particular meanness which is endemic in any large organisation.

Just before Easter 1974 I left the service with one month’s salary of £250 to begin a new life. I was not entitled to an immediate pension, for I had not served the minimum of twenty-two years. However, they had also arbitrarily changed the rules on the long-term pension which I should have got at sixty years of age. They (the faceless ones) had decided that they would not give a long-term pension to anyone who left the service before 1975. Any airman who had served for the same time alongside me and left a year later received his long-term pension.

Bitter?

Moi

? Certainly.

Just before we left RAF Strike Command, High Wycombe, I was lying in bed asleep when Annette burst into the room.

‘Garry!’ she shrieked.

I woke with a horrible start, after one hour’s sleep, having been awake for twenty-four hours doing my last night shift.

‘What?’ I cried, fuzzy-confused. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘You

won

!’ she said, her voice now a profound whisper. ‘You won the short story competition.’

I sat up, electrified. ‘I did?’

‘Here’s the telegram,’ she waved a piece of paper at me. ‘They want you to phone them immediately.’

Thoroughly awake now I ran down to the telephone booth and called the number in the telegram.

‘John Bush, Gollancz.’

‘Mr Bush, my name’s Garry Kilworth.’

‘Aha!’ he said. ‘One of the prize-winners. Congratulations. You’re sharing the prize with another writer. We couldn’t make up our minds between you, but still, very well done. Half-a-thousand pounds. How does that grab you? And we’ll be publishing the story. I think it’ll also be published in the

Sunday Times Review

.’

‘That’s-bloody-marvellous!’ I said, hardly able to catch my breath. ‘Bloody marvellous.’

‘So glad you’re pleased. The prizes will be awarded at the annual Science Fiction Convention a bit later on this year. Anyway, congratulations again and we’ll be seeing you soon.’

Like Alison, in

Peyton Place

, I danced up the street on my way back to the house, shouting hoarsely, ‘I’m an author! I’m an author!’

Lisa came out of the house and gave me a hug and told me ‘Well done, Garry.’

It was the third best day of my life to date, if you count getting married and having two kids, both of which are a given.

I went into High Wycombe and saw

Westworld

at the cinema and bought the latest Carpenters’ LP, the one with the terrific guitar riff in the middle of the song ‘Goodbye to Love’.

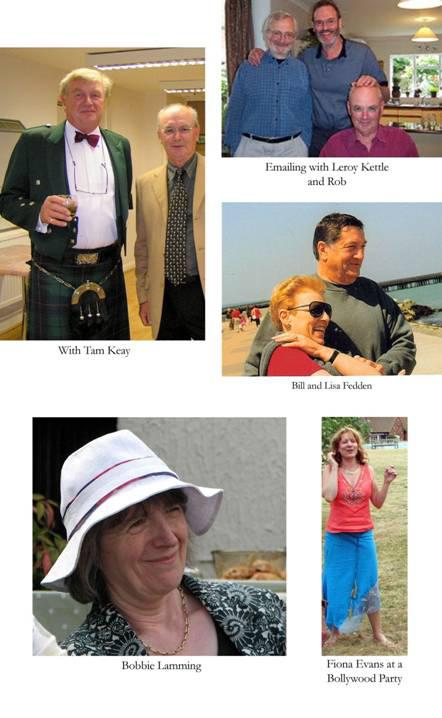

My eyes were opened wide when we attended my first science fiction convention in Newcastle in 1974. This particular convention was called ‘Tynecon’. There’s an organisation called the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA), but they do not formally arrange science fiction conventions. This is done by groups of science fiction fans, who by the by, never use the term ‘sci-fi’but abreviate science fiction to ‘sf’. For the first time I realised their was such a thing as ‘sf fandom’ where enthusiasts of the genre gathered like an outlawed clan.

Around 400 people were at the convention, including famous writers like Brian Aldiss, Bob Shaw and Harry Harrison. There were respected publishers and editors too, but for the most part the clan consisted of like-minded fans. Some were fairly geeky, quite a few really when I think about it, but others were serious scientists. Of the fans, many produced ‘fanzines’ in which sf was discussed, reviews of novels were printed, and the slings and arrows of outrageous insults were employed. The convention itself harboured second-hand booksellers, had an art show, had Guests of Honour (usually writers and artists in the genre), showed movies, had panels and talks, and a fancy dress evening (though many fans wore space suits or Conan-the-Barbarian loin cloths the whole period of the three days) but mostly consisted of groups of fans sitting in the bar downing alcohol and talking about their favourite genre.

I met the Gollancz publisher, John Bush, and he was very complimentary and enthusiastic about my future as a writer, which filled me with confidence. I was also given my prize cheque at the banquet which is always held at such cons on Saturday night. The man or woman who wrote the story ‘The Hibbie’ under the name James Alexander, who shared the prize with me, did not attend and to my knowledge has never been seen or heard of again in the book world. I have long since pondered on who it might have been, given that the story was probably written under a pseudonym. Why does the winner of a prestigious award simply disappear without a trace without ever showing his or her face, or writing another piece of fiction under the same name? I have tried googling ‘James Alexander – Science Fiction’ without the remotest success. There is a James B Alexander, an American author listed in

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

JBA wrote one work which might be regarded as science fiction. This gentleman was born in 1831 and unless time travel has become fact, the mystery remains unsolved.

There were two writers who shared a prize for the best science fiction novel competition too. I remember the Scottish guy letting out a rebel yell when he went up to get his prize. I wish I’d done that, but I was quite shy among all these ‘academics’ and ‘professional writers’. I would soon get to befriend many of them, become one of them, but in those days I was still Sergeant Kilworth, a military man and the antithesis of most of those attending the convention. They were more likely to be New Age, Goths, tarot card readers, pacifists, bearded booksellers, left wing Ban-the-Bombers (well, I was too, though they didn’t know that) or NASA people. I was out of my comfort zone, even though all those I met were warm and friendly and didn’t really care whether or not I was the Marshal of the Royal Air Force.