On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (5 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

Chapter One

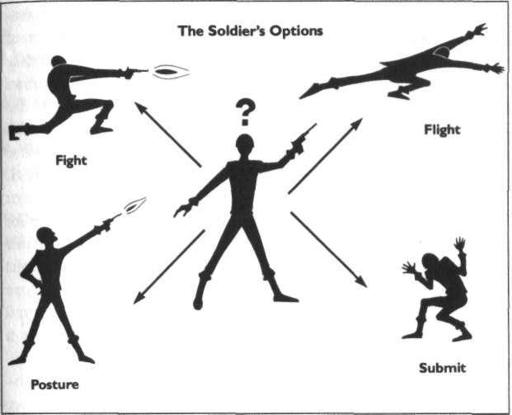

Fight or Flight, Posture or Submit

The notion that the only alternatives to conflict are fight or flight are embedded in our culture, and our educational institutions have done little to challenge it. The traditional American military policy raises it to the level of a law of nature.

— Richard Heckler

In Search of the Warrior Spirit

O n e of the roots of our misunderstanding of the psychology of the battlefield lies in the misapplication of the fight-or-flight model to the stresses of the battlefield. This model holds that in the face of danger a series of physiological and psychological processes prepare and support the endangered creature for either fighting or fleeing. T h e fight-or-flight dichotomy is the appropriate set of choices for any creature faced with danger

other

than that which comes from its own species. W h e n we examine the responses of creatures confronted with aggression from their own species, the set of options expands to include posturing and submission. This application of animal kingdom intraspecies response patterns (that is, fight, flee, posture, and submit) to human warfare is, to the best of my knowledge, entirely new.

T h e first decision point in an intraspecies conflict usually involves deciding between fleeing or posturing. A threatened baboon or 6 KILLING AND THE EXISTENCE OF RESISTANCE

rooster who elects to stand its ground does not respond to aggression from one of his own kind by leaping instantly to the enemy's throat. Instead, both creatures instinctively go through a series of posturing actions that, while intimidating,

are almost always harmless.

These actions are designed to convince an opponent, through both sight and sound, that the posturer is a dangerous and frightening ad-versary.

When the posturer has failed to dissuade an intraspecies opponent, the options then become fight, flight, or submission. When the fight option is utilized, it is

almost never to the death.

Konrad Lorenz pointed out that piranhas and rattlesnakes will bite anything and everything, but among themselves piranhas fight with raps of their tails, and rattlesnakes wrestle. Somewhere during the course of such highly constrained and nonlethal fights, one of these intraspecies opponents will usually become daunted by the ferocity and prowess of its opponent, and its only options become submission or flight. Submission is a surprisingly common response, usually taking the form of fawning and exposing some vulnerable portion of the anatomy to the victor, in the instinctive knowledge that the opponent will not kill or further harm one of its own kind once it has surrendered. The posturing, mock battle, and submission process is vital to the survival of the species. It prevents needless deaths and ensures that a young male will live through early confrontations when his opponents are bigger and better prepared. Having been outpostured by his opponent, he can then submit and live to mate, passing on his genes in later years.

There is a clear distinction between actual violence and posturing. Oxford social psychologist Peter Marsh notes that this is true in New York street gangs, it is true in "so-called primitive tribesmen and warriors," and it is true in almost any culture in the world. All have the same "patterns of aggression" and all have

"very orchestrated, highly ritualized" patterns of posturing, mock battle, and submission. These rituals restrain and focus the violence on relatively harmless posturing and display. What is created is a

"perfect illusion of violence." Aggression, yes. Competitiveness, yes. But only a "very tiny, tiny level" of actual violence.

"There is," concludes Gwynne Dyer, "the occasional psychopath who really wants to slice people open," but most of the

F I G H T O R F L I G H T , P O S T U R E O R SUBMIT 7

participants are really interested in "status, display, profit, and damage limitation." Like their peacetime contemporaries, the kids who have fought in close combat throughout history (and it is kids, or adolescent males, w h o m most societies traditionally send off to do their fighting), killing the enemy was the very least of their intentions. In war, as in gang war, posturing is the name of the game.

In this account from Paddy Griffith's

Battle Tactics of the Civil

War,

we can see the effective use of verbal posturing in the thick woods of the American Civil War's Wilderness campaign: The yellers could not be seen, and a company could make itself sound like a regiment if it shouted loud enough. Men spoke later of various units on both sides being "yelled" out of their positions.

In such instances of units being yelled out of positions, we see posturing in its most successful form, resulting in the opponent's selection of the flight option without even attempting the fight option.

8 KILLING AND THE E X I S T E N C E OF R E S I S T A N C E

Adding the posture and submission options to the standard fight-or-flight model of aggression response helps to explain many of the actions on the battlefield. W h e n a man is frightened, he literally stops thinking with his forebrain (that is, with the mind of a human being) and begins to think with the midbrain (that is, with the portion of his brain that is essentially indistinguishable from that of an animal), and in the mind of an animal it is the one w h o makes the loudest noise or puffs himself up the largest who will win.

Posturing can be seen in the plumed helmets of the ancient Greeks and Romans, which allowed the bearer to appear taller and therefore fiercer to his foe, while the brilliantly shined armor made him seem broader and brighter. Such plumage saw its height in modern history during the Napoleonic era, when soldiers wore bright uniforms and high, uncomfortable shako hats, which served no purpose other than to make the wearer look and feel like a taller, more dangerous creature.

In the same manner, the roars of two posturing beasts are exhibited by men in battle. For centuries the war cries of soldiers have made their opponents' blood run cold. Whether it be the battle cry of a Greek phalanx, the "hurrah!" of the Russian infantry, the wail of Scottish bagpipes, or the Rebel yell of our own Civil War, soldiers have always instinctively sought to daunt the enemy through nonviolent means prior to physical conflict, while encouraging one another and impressing themselves with their own ferocity and simultaneously providing a very effective means of drown-ing the disagreeable yell of the enemy.

A modern equivalent to the Civil War occurrence mentioned above can be seen in this Army Historical Series account of a French battalion's participation in the defense of Chipyong-Ni during the Korean War:

The [North Korean] soldiers formed one hundred or two hundred yards in front of the small hill which the French occupied, then launched their attack, blowing whistles and bugles, and running with bayonets fixed. When this noise started, the French soldiers began cranking a hand siren they had, and one squad started running toward the Chinese, yelling and throwing grenades far to the front F I G H T OR F L I G H T , P O S T U R E OR SUBMIT 9

and to the side. When the two forces were within twenty yards of each other the Chinese suddenly turned and ran in the opposite direction. It was all over within a minute.

Here again we see an incident in which posturing (involving sirens, grenade explosions, and charging bayonets) by a small force was sufficient to cause a numerically superior enemy force to hastily select the flight option.

With the advent of gunpowder, the soldier has been provided with one of the finest possible means of posturing. " T i m e and again," says Paddy Griffith,

we read of regiments [in the Civil War] blazing away uncontrollably, once started, and continuing until all ammunition was gone or all enthusiasm spent. Firing was such a positive act, and gave the men such a physical release for their emotions, that instincts easily took over from training and from the exhortations of officers.

Gunpowder's superior

noise,

its superior

posturing

ability, made it ascendant on the battlefield. The longbow would still have been used in the Napoleonic Wars if the raw mathematics of killing effectiveness was all that mattered, since both the longbow's firing rate and its accuracy were

much

greater than that of a smoothbore musket. But a frightened man, thinking with his midbrain and going "ploink, ploink, ploink" with a bow, doesn't stand a chance against an equally frightened man going " B A N G ! B A N G ! " with a musket.

Firing a musket or rifle clearly fills the deep-seated need to posture, and it even meets the requirement of being relatively harmless when we consider the consistent historical occurrences of firing over the enemy's head, and the remarkable ineffectiveness of such fire.

Ardant du Picq became one of the first to document the common tendency of soldiers to fire harmlessly into the air simply for the sake of firing. Du Picq made one of the first thorough investigations into the nature of combat with a questionnaire distributed to French officers in the 1860s. O n e officer's response to du Picq 10

KILLING AND THE E X I S T E N C E OF R E S I S T A N C E

stated quite frankly that "a good many soldiers fired into the air at long distances," while another observed that "a certain number of our soldiers fired almost in the air, without aiming, seeming to want to stun themselves, to become drunk on rifle fire during this gripping crisis."

Paddy Griffith joins du Picq in observing that soldiers in battle have a desperate urge to fire their weapons even when (perhaps especially when) they cannot possibly do the enemy any harm.

Griffith notes:

Even in the noted "slaughter pens" at Bloody Lane, Marye's Heights, Kennesaw, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor an attacking unit could not only come very close to the defending line, but it could also stay there for hours — and indeed for days — at a time.

Civil War musketry did not therefore possess the power to kill large numbers of men, even in very dense formations, at long range. At short range it could and did kill large numbers,

but not

very quickly

[emphasis added].

Griffith estimates that the average musket fire from a Napoleonic or Civil War regiment (usually numbering between two hundred and one thousand men) firing at an exposed enemy regiment at an average range of thirty yards, would usually result in hitting

only one or two men per minute!

Such firefights "dragged on until exhaustion set in or nightfall put an end to hostilities. Casualties mounted because the contest went on so long, not because the fire was particularly deadly."

Thus we see that the fire of the Napoleonic- and Civil W a r - e r a soldier was incredibly ineffective. This does not represent a failure on the part of the weaponry. John Keegan and Richard Holmes in their book

Soldiers

tell us of a Prussian experiment in the late 1700s in which an infantry battalion fired smoothbore muskets at a target one hundred feet long by six feet high, representing an enemy unit, which resulted in 25 percent hits at 225 yards, 40

percent hits at 150 yards, and 60 percent hits at 75 yards. This represented the potential killing power of such a unit. T h e reality is demonstrated at the Battle of Belgrade in 1717, when "two F I G H T O R F L I G H T , P O S T U R E O R SUBMIT

11

Imperial battalions held their fire until their Turkish opponents were only thirty paces away, but hit only thirty-two Turks when they fired and were promptly overwhelmed."

Sometimes the fire was completely harmless, as Benjamin McIntyre observed in his firsthand account of a totally bloodless nighttime firefight at Vicksburg in 1863. "It seems strange . . . ,"

wrote McIntyre, "that a company of men can fire volley after volley at a like number of men at not over a distance of fifteen steps and not cause a single casualty. Yet such was the facts in this instance." The musketry of the black-powder era was not always so ineffective, but over and over again the average comes out to only one or two men hit per minute with musketry.

(Cannon fire, like machine-gun fire in World War II, is an entirely different matter, sometimes accounting for more than 50

percent of the casualties on the black-powder battlefield, and artillery fire has consistently accounted for the majority of combat casualties in this century. This is largely due to the group processes at work in a cannon, machine-gun, or other crew-served-weapons firing. This subject is addressed in detail later in this book in the section entitled "An Anatomy of Killing.") Muzzle-loading muskets could fire from one to five shots per minute, depending on the skill of the operator and the state of the weapon. With a potential hit rate of well over 50 percent at the average combat ranges of this era, the killing rate should have been hundreds per minute, instead of one or two. The weak link between the killing potential and the killing capability of these units was the soldier. The simple fact is that when faced with a living, breathing opponent instead of a target, a significant majority of the soldiers revert to a posturing mode in which they fire over their enemy's heads.