Okay for Now (4 page)

Authors: Gary D. Schmidt

"That's not how you drink a really cold Coke," she said.

"What?"

"That's not how you drink a really cold Coke."

"So how do you drink a really cold Coke?"

She smiled, raised the Coke to her lips, and tipped the bottle up.

She gulped, and gulped, and gulped, and gulped, and gulped. The ice on the bottle's sides melted

down toward her—and she gulped, and gulped, and gulped.

When she finished, she took the bottle away from her lips—she was still smiling—and she sighed,

and then she squared her shoulders and kind of adjusted herself like she was in a batter's box, and

then she let out a belch that even my brother couldn't match, not on his very best day.

It was amazing. It made birds fly out of the maples in front of the library. Dogs asleep on porches a

couple of blocks away probably woke up.

She put the bottle down and wiped her lips. "That's how you drink a really cold Coke," she said.

"Now you."

So what would you do? I lifted the Coke to my lips, tipped the bottle up, and gulped, and gulped,

and gulped. It was fizzing and bubbling and sparkling, like little fireworks in my mouth.

"You know," she said, "it's a little scary to see your Adam's apple going like that."

The fireworks exploded—and I mean exploded.

Everything that was fizzing and bubbling and sparkling went straight up my nose and Coke started

to come out all over the library steps and it wasn't just coming out of my mouth. I'm not lying. By the

time the Coke was done coming out of both places, my eyes were all watered up like I was about to

bawl—which I wasn't, but it probably looked like I was—and there was this puddle of still fizzing

Coke and snot on the steps, and what hadn't landed on the steps had landed on my sneakers, which, if

they had been new, I would have been upset about, but since they had been my brother's, it didn't

matter.

"If you—"

"Don't get mad," she said. "It's not my fault that you don't know how to drink a really cold Coke."

I stood up. I tried shaking the Coke and other stuff off my sneakers.

"Are you going to keep waiting for the library to open?" she said.

"No, I'm not going to keep waiting for the library to open."

"Good," she said. "Then do you want a job?"

I looked down at her. There was still a little Coke up my nose, and I was worried that it was going

to start dribbling out, which would make me look like a chump.

"A job?" I said.

"Yes. A job for a skinny thug."

"What kind of a job?"

"A Saturday delivery boy for my father."

"A delivery boy?"

She put her hands on her hips and tilted her head. "Fortunately, you don't have to be too smart to do

this."

"Why me? I mean, there's got to be a hundred kids in this town you could have asked."

"Because you have to deliver stuff out to the Windermere place and everyone's afraid of her and no

one wants to go. But you're new and you don't know anything about that so you seem like the perfect

guy. What's your name?"

"Thug," I said.

She tilted her head back again.

"Doug," I said.

"I'm Lil, short for Lily, short for Lillian. So finish your Coke—but don't let your Adam's apple do

that thing."

And that's how I got the job as the Saturday delivery boy for Spicer's Deli—five dollars a

Saturday, plus tips—which, if you ask me, is pretty impressive for having been in stupid Marysville

for only two days. Even my father said I'd done good. Then he added that it was about time I earned

my keep around the place. When did I start?

"A week from Saturday," I said.

"If they thought you were any good, they would have started you

this

Saturday," he said.

Terrific.

CHAPTER TWO

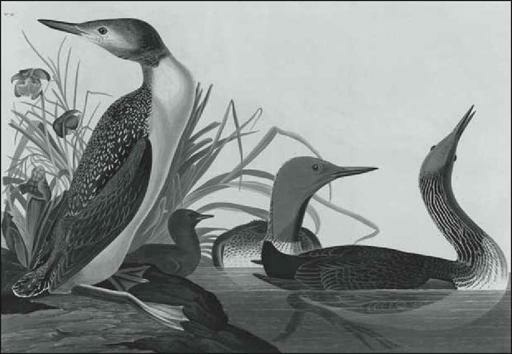

The Red-Throated Diver

Plate CCII

THE NEXT SATURDAY—the Saturday before I was going to begin my new job at Spicer's Deli, which if

they thought I was any good I would have been starting now—I was waiting on the library steps.

Again.

People who passed by looked at me like I didn't belong.

Again.

I hate stupid Marysville.

Every few minutes I went up the six steps to the library doors and tried them and they were, of

course, still locked, so I'd go sit down. I waited for what must have been an hour, until finally the

woman with her glasses on a chain looped around her neck—she already had them looped around her

neck even though she wasn't even in the library yet—she came walking up the block and climbed the

steps and looked back down at me like I was trespassing.

"The Marysville Free Public Library does not open until ten o'clock," she said.

"I know," I said.

"These steps were not made for people to sit on," she said, "especially since you might get in the

way of others who would wish to use them."

I looked up and down the block, then moved way over to the edge of the steps. "Dang," I said. "I

didn't see all the people jamming to get inside. Don't they all know that the Marysville Free Public

Library does not open until ten o'clock?"

She sniffed. I'm not lying. She sniffed. "Go find some other place to be rude," she said.

"Is this one reserved for you?" I said.

I know. I was sounding like Lucas.

She took out a key from her purse, put it into the door and opened it, and went inside. She clanged

the door shut behind her. She turned the bolt in the lock hard enough for me to hear.

I hate this stupid town. I hate it.

I waited on the steps. Right in the middle of them. My legs all spread out as far as I could spread

them.

It wasn't too much longer before an old guy came from the other direction. He had glasses on a

chain looped around his neck too, and I almost told him what a jerk he looked like with glasses

looped around his neck, except I figured it wouldn't make any difference. He probably wouldn't even

care that he looked like a jerk.

"You're an eager one," he said. "But the library doesn't open until ten o'clock."

"That's what I've been told," I said.

And he laughed, like there was something funny about that.

"I see you've met Mrs. Merriam. Is that why you're sitting like that?"

I looked at him. He had hair coming out of funny places—like his ears, his nose, between his eyes.

He didn't need the looped glasses to look like a jerk.

"I guess," I said.

"You should be glad she hasn't called a policeman to have you removed." He pulled out a pocket

watch—I'm not lying, a pocket watch—and flipped it open. "It's already past nine thirty," he said. "I

don't think we'll undermine all law and order in the state of New York if I let you in early."

He put his pocket watch back and then took the steps kind of slowly. He puffed his breath out when

he reached the top. "There seems to be more of these every time I climb them," he said, and took a key

from his pocket.

The library was even cooler than it had been a week ago, and darker, since the only light came

through windows that were stained yellow and didn't let in all that much.

Mrs. Merriam glanced up from the desk, and when she saw me, the look on her face was the look

she probably gave to the bottom of her shoe when she stepped in something that she didn't want to

step in.

"The library does not open until ten o'clock," she said.

"Exactly right," said the man, who was still puffing a little.

"Mr. Powell," she began.

"Just this once," he said.

"You don't know the meaning of

just this once.

How many times have you let the Spicer girl in

early

just this once?

"

"For which she will one day thank us when she dedicates her first book to the Marysville Free

Public Library." Mr. Powell turned to me. "Perhaps you will do the same. Now, is there anything I can

point you toward?"

I shook my head. "I'll look around."

He nodded. "If I were you," he said, "I'd start in the nine hundreds, over there—but that's because

I've always been partial to biography."

I didn't go over to the 900s. First I tried the 500s, which looked pretty dull if you ask me, and then

over to the 600s, which looked a whole lot duller, and I'm not lying. The 700s were better, and I

looked through a bunch of them to see if I could find a picture of the Arctic Tern. But I couldn't.

I guess you're wondering why I didn't go up to the book on the second floor right away. I mean,

that's what I was there for, not for some stupid biographies in the 900s. But I think it was because I

didn't want Mrs. The-Library-Isn't-Open Merriam's eyes looking at me like I was something on the

bottom of her shoe when I went up there. I just didn't.

So I messed around in the 700s looking for the tern until I saw Mr. Powell head over to the front

doors to unlock them so the bezillion people who had been waiting outside and probably spreading

themselves all over the six steps could come in, and some did, and the library began to hum with talk

that carried because of the marble, and Mrs. Merriam adjusted her looped glasses and started

checking in returned books and telling people to keep their voices low, and I crossed the hall and

went up the stairs.

No one had come up here yet, so the lights hadn't been turned on. But the Arctic Tern was still

there, falling. The morning sun that slanted through the windows—they were stained yellow up here

too—the sun showed the water darker, and rougher. And the terrified eye.

I put my pretend pencil over the glass case again, and I started drawing the wings. I drew the lines

down from the wingtips, and then sharply back up into the body. I tried to fill in the six rows of

feathers, keeping them all the same in each row until I came in close, where the feathers faded into the

body—dang, they looked like fur. I could feel the wind rush over their tightness. Then, following the

line down the bird toward the water, curving it up around his neck a little—no, a little less, and then

back down again toward the water, ending at the perfect point of his lower beak, where it stopped

being beak and became air.

And then the light snapped on.

Mr. Powell.

Puffing. A lot.

He looked at me, a little surprised. (He had his glasses on, instead of looped across his chest, so he

didn't look like too much of a jerk.) "I'm sorry," he said. "I should have turned these lights on sooner."

"It doesn't matter," I said.

He walked over to the glass case and looked down into it. "

Sterna arctica,

" he said.

I looked at him. "Arctic Tern," I said. I didn't want him to think I was a chump, like I didn't know

the bird.

"That's right," he said. "There used to be a little card around here somewhere. Isn't it a beauty? You

can feel it plummeting through the air."

I didn't say anything.

"I came up to turn the page. I do it once a week. But I can wait, if you want."

I shrugged.

He looked down again at the Sterna bird. "I think I'll wait," he said.

"Who drew this?"

He turned and pointed to the picture on the wall. "He did. John James Audubon. Almost a hundred

and fifty years ago." He looked into the glass case. "You want to try drawing it yourself ?"

I shook my head. "I don't draw."

"Ever try?"

"I said, 'I don't draw.'"

"So you did. I'll leave the book open to this page, and if you change your mind or want to read

about the artist, I'll—"

I turned and left before he could finish. What a jerk. Didn't he hear me say I don't draw? Chumps

draw. Girls with pink bicycle chains draw. I don't draw. Was he old

and

deaf ?

I hate this town.

A week later, I wasn't at the library when it opened at ten o'clock, and if you've been paying attention,

you should know why. I was over at Spicer's Deli before nine, still tasting the salt-and-peppery fried

eggs that my mother had made for me before I left. Mr. Spicer and Lil were standing by two wagons,

and one was already packed with filled brown bags. "Lil will have the second one waiting for you by

the time you get back from this first run," Mr. Spicer said. He handed me a drawn map with the houses

of the customers marked and told me the order I should go in, which depended on how far away the