Of Merchants & Heros (22 page)

Afterwards, pleased as a child, I paused outside the shop to look over my purchases. Through the window I overheard the bookseller’s voice say in a tone of hushed mock-horror to his friend, ‘A Roman buying books! Whatever next? Do you suppose he can read?’

I was tempted to cough, to let him know I was there. But in the end I just smiled to myself, took up the parcel, and walked off. What mattered was what I made of myself; not what this fussing bookseller thought of me, or of Mouse, or of any Roman.

It was two days later, while I was arranging to send the books to Italy, that the trouble began.

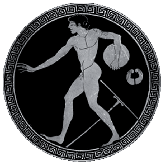

I was on my own that day, Menexenos having been summoned to the gymnasion for athletics practice prior to the games. I had gone down to Piraeus to meet a sea captain I knew from my days in Tarentum, an old Syracusan by the name of Kratos, who owned his own ship and plied the route between Greece and Sicily. He had agreed to deliver my package for Mouse, and to take a letter for Titus.

We met at the appointed time, beside the sanctuary of Aphrodite on the sea front. I gave him my parcels, and we paused to talk.

There was a good deal of noise all about us – stevedores shouting and chanting; street-sellers; crewmen calling; the sound of wood on wood as crates were piled up, or loaded onto carts – but like a dog that catches a scent in the air, Kratos discerned among all this something that made him break off in mid-speech and cock his head.

He listened, and under his beard his face hardened.

‘What is it?’ I said.

He looked from side to side, and then behind him. ‘Trouble, that’s what.’

And then I heard it. From the south harbour, which lay on the other side of Piraeus a few streets away, there came shouts of alarm echoing between the buildings.

Kratos peered down the quay to where his own ship lay moored beyond a row of four Athenian triremes. It was secured to the quay only by a single line, ready to cast off.

On the deck the crew were waiting, craning their necks and looking about with serious faces. They too had heard the commotion.

Kratos scanned the water and the mole, then gave a quick signal to his helmsman. From the stern the helmsman raised his hand in acknowledgement. Then he turned back to me.

‘I’m off, and I suggest you do the same. I’ve seen harbour riots before. I’m not going to wait around for my ship to be looted or burned.’

He briefly shook my hand, assured me my parcel would be delivered, then hurried off to his waiting ship, throwing the mooring-line off the bollard as he passed it. The crew shoved off, and the short manoeuvring oars began to beat the water.

A sailor had appeared on the deck of the nearest trireme. He was calling, waving his arms and gesturing to someone at the far end of the quay beyond my view, asking what was afoot. Two workmen came up from below to see. But otherwise the triremes were unmanned. Beyond, I saw Kratos’s ship at the harbour entrance. The great striped sail dropped and filled out in the breeze; the crew busied themselves with the rigging.

All about me on the quay, men were leaving off what they were doing. I turned to go. And then I saw the first of the great painted Macedonian war-galleys rounding the sea wall, its deck bristling with armed soldiers.

But it was not the soldiers bearing down on me that made me gape and stare.

He was standing in the prow, with one arm slung around the carved painted figurehead. He had tied back his flaxen hair, and in his hand he brandished a sword.

He turned, smiling and laughing to those behind him. A chill went through me. My hands went cold, and my breath stopped in my throat. It was Dikaiarchos.

I don’t know what my first thought was. All along the quay people were crying out and running towards the back streets. My ears rang with the sound of my own heart beating, and it seemed the world moved slowly, and the sounds came from a great distance. It was as if some dark inner part of me, some creature of my nightmares, had appeared before my eyes, and the rest of the world had dimmed. I glanced round. But I knew I should not run.

I turned back. Two more warships had appeared, entering the harbour at full speed, their oars thrashing the water. I saw Kratos’s ship pass the end of the mole, where the lighthouse is, moving the other way. The Macedonians took no notice. Whatever they had come for, Kratos was no part of it.

I forced my thoughts into order. I was unarmed. I did not even have a hunting knife (something I always used to carry in Praeneste).

I cast my eyes about for something to use as a weapon. One of the workmen from the moored trireme shoved past me. ‘Hey!’ I cried. But he ran on, not heeding, his face a mask of terror.

The sailor who had been calling was staring now across the water at the approaching Macedonians. I could not tell if it was bravery that stopped him running, or fear. Then, as I looked, I saw a stack of javelins, stowed on the deck, not far from where he was standing.

I scrambled up the gangboard. The weapons had been strapped down. I began tugging at the leather binding. From the poop-deck the sailor shouted, ‘You there! What are you doing?’

The binding came away and I pulled a spear from the top of the pile. ‘I am going to fight,’ I answered. ‘And you?’

For a moment he stared at me as if it had occurred to him only now that there might be a battle. He was a young sea-cadet, an ephebe on military training. His first beard showed like fine down on his cheeks.

But whatever was going through his head took only a moment.

He leapt down beside me, and seized a javelin from the pile. ‘I fight,’

he said, looking at me squarely.

And then we turned to face the enemy.

The first of the Macedonian warships had come alongside. Troops were leaping down and forming a defensive circle. Then, seeing they were unopposed, they began swarming along the quay. The leading ship stood out. From the prow Dikaiarchos was shouting out orders, pointing and waving his arms. The harbour front was deserted, the ground strewn with abandoned carts and crates and baskets. The Athenians had clearly been taken by surprise. There was no sign of defenders anywhere.

The young Athenian beside me saw all this and met my eye. He had a gentle, expressive face. I could see his mind working in his features, summoning up his courage. His jaw firmed, and he gave an almost imperceptible nod, as if to say: If today is the day, then so be it – I shall die a credit to my people, and to myself. Then his muscles tensed, he balanced his spear in his hand, aimed it, and threw.

He had aimed well. The shaft sliced through the air and impaled a running soldier, catching him in the throat, where his cuirass did not protect him. Then I threw too, and hit the man behind him. We grabbed fresh spears from the stack and took aim for a second time.

All of a sudden, just as I was in the middle of my throw, the deck under me lurched, making me stumble and causing my spear-throw to falter. I swung round to look, thinking we had been rammed.

Behind, on the side facing the water, the warship bearing Dikaiarchos had come alongside us. The Macedonians were struggling with ropes and hooks, preparing to board.

I ducked down and grabbed two more spears, tossing one to the Athenian. He caught it expertly with one hand and we advanced together. The Macedonian troops were boarding now – warily at first, in case we had reinforcements waiting below. It would not take them long to realize we were alone.

But my mind was not on that: I was watching Dikaiarchos. From the Macedonian ship he was calling, ‘Cut the lines – quickly now.’

His fox’s eyes were bright and darting; he wore a cuirass embossed with a bursting sun, and where his bare skin showed from under it, it was deep-tanned, brown as walnut. All the while, as he shouted out orders, he was smiling and laughing. He was enjoying himself, like some wild child let out to play.

I took careful aim.

Running feet sounded on the deck behind me. I should not get another chance. I inserted my finger in the javelin-thong, bent my knees, and balanced the shaft in my palm.

Dikaiarchos had been looking away. Just then, someone shouted up to him. He broke off what he was saying and began to turn. I drew the air into my lungs, and with a great cry and twist of my body I let the spear fly, just as his eyes met mine.

His brows went up. A look of surprise crossed his face. Then the javelin was home.

I had aimed for his throat. I do not know if my aim was bad, or whether the ships moved. The spear came to a jarring halt in the neck of the carved figurehead, at the place where his hand held it.

I stared, appalled, knowing I had no other chance. Then his hand moved, and I saw the smear of his blood on the painted wood.

There was no more time. The Macedonians were upon us. The young Athenian ephebe leapt down to the lower deck. Three of them rushed at him.

The first one he killed. I leapt across the deck, snatched up another javelin, and took aim. But even as I did so, someone seized me from behind, jerking my arm back, twisting the weapon from my hand.

I heard the Athenian cry out and turned my head. A group of Macedonians had closed around him. The steel of their swords flashed in the sun, crimson with his lifeblood. He did not cry out again.

My other arm was pinned back. I could feel the heat of the man’s body behind me. I held my breath and waited for the deathblow.

There was a pause. The blow did not come. Then I heard a voice saying, ‘Leave him; leave him for me,’ and Dikaiarchos stepped into view.

But he did not turn his attention to me straight away. For a while he was occupied with directing the men, calling to the ships, shouting orders across the quay. Men began to scramble below deck.

Only then did I realize what was happening: the Macedonians were manning the triremes.

I turned my head. Already the mooring lines had been cut. They hung limply from their bollards. The ship was yawing, parting from the quay. Down below I could hear men taking their places on the rowing-benches, and the clatter of the oarlocks. Dikaiarchos was stealing the Athenian warships.

Order returned. The oars began to beat the water. The ship moved out into the middle of the harbour, gaining speed. I saw two troopers carry off the corpse of the young Athenian and sling him over the side. Then Dikaiarchos crossed the deck and stood before me.

I wondered whether he would know me; but he showed no signs of it.

He raised his left hand, holding it in front of my eyes. Blood oozed from a wound, where my javelin had pierced him. He glanced aside, and held out his arm, and at this the soldier beside him handed him his sword. I noticed, as he gripped it, his eyes narrowed momentarily in pain. Then he took a pace forward, and levelled the point at my throat.

The sunlight glanced off the flat of the blade, dazzling me. I waited for the final thrust. But with a sudden swift movement he drew the sword aside, and I felt the sting of the blade as it cut into my forearm.

‘Like for like,’ he said with a grim smile, and I realized he did not intend a swift death for me; he was going to torture me first.

‘Kill me!’ I yelled at him.

He stepped up close, and gripped my chin hard in his bloody hand. I could feel his breath, and smell the rank smell of his sweat and his blood. All the time his eyes were locked on mine; I felt the power of his life force like something surging and living within me.

He paused, then drew back grinning. ‘Not now; there will be another time for us, my beautiful black-haired friend.’

Then his arm shifted, and he stood back.

He glanced to one side. We were far from the quay now, nearing the harbour entrance.

‘It’s a shame to cast you away,’ he said. ‘I could have enjoyed you; but I cannot have Romans here. Now let us see if you can swim.’

He turned to the Macedonian trooper beside him and said, ‘Throw him off!’

EIGHT

‘HOLD STILL, WILL YOU?’

‘I am holding still.’

‘It’s as well you can swim.’

‘Well I can. You know I can.’

‘Even so, you shouldn’t fight without the right weapon. It’s madness. What did you think you were doing? Taking on the whole of Macedon yourself?’

‘You’re angry.’

He frowned at the bandage he was fixing on my arm and gave it another tug.

‘Menexenos, listen. It was him. It was Dikaiarchos. I already told you.’

‘I know; I know.’

‘But you are angry all the same.’

‘If he hadn’t realized you were Roman, I’d be dressing your corpse, just as poor Eudoxos’s father is doing.’

I fell silent, remembering the Athenian ephebe who had fought with me. I had seen his father’s face, when he came to claim the body.

I said, ‘Well I am here.’

‘Yes. Some god is watching over you.’ He paused and sighed. ‘I don’t want to lose you. Not yet. I have only just found you.’

We were sitting on the edge of the bed, side by side. Using my good arm I gently turned his face to mine, and kissed his mouth.

‘You will never lose me, Menexenos.’

‘I said keep still,’ he said grumpily, pushing me away. But I could tell from his voice that he was softened.

I sat still, and he finished the last knot on the bandage.