Of Merchants & Heros (10 page)

But presently Villius said, ‘While I was in Rome I saw Lucius.

They have quarrelled again, he and your father.’

Titus paused. For an instant, such a look of anger clouded his features that Xanthe, who had been resting her hand on his, took it hurriedly away.

With a quick apologetic smile he took it back and held it in his own broad hand. ‘No,’ he said. ‘It’s not your fault.’ And then, to Villius, ‘They always quarrel. That is what Father does best. Lucius needs to get away. I shall write to him again and ask him to come.

He is my brother, after all, whatever his faults, and I must do what I can.’

The tables were cleared. A dancer came on, a lithe dark-skinned Greek boy from Tyre, who danced to the accompaniment of pan- pipes and a lute. Xanthe, who was sitting on the other side of me, was asking in wide-eyed curious tones about Rome, which she seemed to regard as a fearsome barbarous place, far distant and never to be visited, like the lands of the painted Kelts, or the Hyperboreans. We were speaking lightly, and laughing. The dancer, naked but for his loincloth, moved in the lamplight; the pipes played their prancing melody. Then, like a sudden ice-wind on a summer’s day, from across the room I heard a name that made me jerk my head around and stare.

One of Titus’s friends, one of the Greeks, was talking about King Philip, king of the Macedonians. But it was not the sound of Philip’s name that jolted me. It was Dikaiarchos’s.

Titus saw me stiffen and look.

‘What is it?’ he said. ‘Do you know this man?’

I said, ‘I shall never forget, and one day I shall kill him.’

I had not intended to say this. But now the words were out, and so, with everyone’s eyes on me, I explained why.

When I had finished, Titus’s friend – his name was Mimas – said, ‘Well I am sorry. If you ask me, we are all going to hear a lot more of him.’

I asked him why.

‘He has been seizing Roman grain ships, and nothing is more likely to draw the Senate’s attention than that. Everyone says Philip is behind it, though he denies it of course. But he and Dikaiarchos are guest-friends.’ He raised his black brows, and with a smiling glance about the room added, ‘There are some, indeed, who say they were once lovers . . . But however that may be, they are certainly thick as thieves. You should keep your eye on them, Titus. Scipio won glory by driving Hannibal from Italy. What could be nobler than freeing Greece from under the heel of that bully Philip?’

Titus stroked the soft boyish beard on his chin. He took up his cup, and his blue eyes shone. I remember that moment, not only for my own sake, but because I saw the end, and what became of it. I have often wondered, after, whether this was the beginning.

The party broke up soon after.

While I stood on the porch outside, waiting for the torch-bearers, Pasithea came up and kissed my brow.

‘Be sure to come and visit me,’ she said, as if it were only me that had made the whole evening worthwhile. ‘Anyone knows where I live.

I’ll send my boy with a note.’

Then the torch-bearer came, and she went off across the garden and under the arch, the goldwork in her long sweeping dress catching in the light from the cressets as she moved.

FOUR

SPRING CAME. PRIMROSES SHOWED

on the slopes among the cypresses, and the port, which had been quiet for the winter, grew busy once more.

My stepfather had gone out early, down to the harbour with Florus and Virilis. I was in the garden when I heard from within a great commotion of shouting and rushing of feet. Then Caecilius appeared on the step. He looked as if he had run all the way up the hill from the marketplace. His face was red and blotchy, his breath labouring.

‘He’s dead!’ he cried, throwing up his hands. ‘He’s dead!’

Florus appeared beside him in the doorway, and then Virilis, both of them eager-faced and full of moment.

‘Who is dead?’

‘Why, the praetor!’ cried Caecilius, staring at me as if I were an idiot. ‘Caeso! He died less than an hour ago, with the dawn. It’s all over the market.’

‘But his wounds were healing.’

‘Maybe he caught a chill – who can say? But anyway he is dead.

You must go with your condolences . . . Make sure it is noticed. Go and change those clothes – hurry! Go now, while the news is fresh, before the crowds arrive.’

I changed my clothes and made my way to the praetor’s house.

The crowds were already there – flatterers, opportunists, sycophants, men on the make, all of them full of eager showy grief. I left again without speaking to anyone.

The next we heard was that Titus had stepped in, assuming the imperium from his uncle. He had been doing the governor’s work already; and in due course the Senate, with its eyes fixed elsewhere on the war with Carthage, approved it.

During this time, Titus was much occupied with the affairs of government, and I with my stepfather’s business. I had not seen him for a while. But one morning I was returning from some errand, and was passing by the gardens of the sanctuary of the Dioskouroi, which, just then, were heavy with almond blossom, when I saw him, standing with his back to me, close to the gateway that leads out to the marketplace.

It was early, and the stallholders were still setting up. I was rather surprised to see Titus there. It was not his habit to dawdle around the market, and, though he did not go about town with a formal retinue, which he said the Tarentines would resent, nevertheless he would usually have two or three friends with him.

I crossed along the portico to greet him. As I drew near I sensed there was something about him not quite right. His hair was the same, falling in brown tufts about his neck. But he held himself oddly, as if he were tired or ill. Or – it came to me even as I spoke his name – drunk. But that could not be. Titus never allowed himself to get stumbling drunk anywhere, let alone in the public marketplace.

He turned and stared into my face with cold unfocused eyes. I felt a chill down my spine. It is a strange unsettling thing not to be recognized by a man you count as a friend.

‘Do I know you?’ he said harshly.

And then realization dawned.

‘What is wrong with you?’ he said. ‘Do you lack eyes to see?’

I spluttered out an apology.

‘Then look and remember,’ he said, unforgiving. ‘I am not Titus. I am Lucius.’

So Lucius has come then, I thought to myself as I hurried away.

And then it came to me where he had emerged from. It was the alley behind the portico, where the rough taverns were, the ones that open at dawn to cater for the market traders, and for men who cannot get through the morning without a cup of wine.

I regretted my mistake. I hoped, when I next saw him, I would be able to make a better apology. But I did not dwell on it, for just then something closer to home had begun to trouble me.

It had started towards the end of winter, and at first I did not credit what I saw. It was a habit from my childhood to rise each day with first light. One morning I was in the garden alone, sitting on the bench beside the wall, when I saw a girl flitting along the portico.

She paused by a column, ran her fingers through her hair and straightened her mantle, then, with a quick look about her, darted up the steps and into the inner hall. She had not seen me. There was a spreading jasmine that grew up the side of the house. It had concealed me from her view.

I sat back and smiled to myself, and at the time thought little of it, supposing she was some friend of one of the slaves. My stepfather forbade such visits. She was leaving before he awoke.

But when one looks, one notices. A few mornings later I saw her again. She was less discreet this time, more sure of herself. Once again she paused to arrange her clothes, and this time I took a better look at her. She had thick black hair, and wore a cheap necklace of copper and glass beads. The strap of her shoe was troubling her, and as she snatched at it with her fingers a sharp shrewish expression passed across her features. She had the look of a Phoenician or Sicilian, a thin face with a pointed chin; one saw many of them in Tarentum, especially at the port.

When she disappeared inside I followed, and from the porch saw her exit through the main gateway and hurry off down the street, keeping to the side, out of the light. I returned to the inner garden, and this time followed the direction from which she had first emerged. At the far end of the portico, concealed behind a clump of oleander, was a doorway in the wall, and beyond an open passageway which ran along the back of the house, strewn with dead leaves. At the far end, at the top of a flight of stone steps, was a back door to my stepfather’s sleeping-suite. The girl’s footprints showed in the dust.

I returned to the bench beneath the jasmine and considered. I shall not pretend I was greatly surprised. I told myself what one hears everywhere: that a man’s pleasures are his own. Yet I found myself filled with distaste. This was not just any man; he was the man who had chosen to marry my mother.

Nothing of the varied diversions of Tarentum had seemed to interest him. I recalled with an ironic smile how he had declared, primly, that he did not have time for such frivolity as the theatre or the concerts at the odeion, or the pleasant garden walks. I reflected too that, for all his money, he had chosen only this harsh-faced trull as a companion. Yet how could it be otherwise? He would never have picked a woman with the charm and refinement of Xanthe or Pasithea. They would have shown him up for what he was.

When, later, he finally emerged from his rooms, dull-eyed and irritable, for my mother’s sake I did not mention the girl. But when, later in the day, he snapped that he was tired, I allowed myself to say, ‘You should do your best to sleep more, sir, in spite of all this work. You are getting no younger, after all, and look what happened to Caeso.’

When Titus next invited me to one of his dinner-parties, his brother Lucius was there. As soon as I could do so discreetly, I made my apologies for my mistake. He seemed to accept them; but he looked at me oddly, as if he did not know what I was talking about. Perhaps this was how he showed I was forgiven. It was disconcerting, in one who looked so like Titus, to find his manner so different. From a distance they looked identical. The same chin and brow and falling brown hair, the same regular features. But there was a sullenness about his mouth and eyes, like an ill-bred child’s deprived of what it wants.

There was always a studied Greekness to these gatherings. A youth or a girl would gently sing to the accompaniment of a lyre or flute; or, at other times, Titus would arrange for some well-known rhapsode from Tarentum or other of the Greek cities in Italy to recite tales of heroes and ancient love. There was style in everything, and careful good manners.

All this I noticed, because it was new, and diverting, and exotic. I noticed too that it seemed to irk Lucius. He talked over the music; he complained that the service at dinner, with its carefully chosen, exquisitely prepared portions, was too slow; but most of all he complained about the wine, for he was a man who liked to drink at his own pace, which was faster than anyone else’s. To make his point, he would drain his cup no sooner than the serving-boy had filled it, then indicate it was empty by setting it down loudly on the little olivewood table in front of his couch and gesturing with a snap of his finger for the boy to refill it.

Not surprisingly, after the way we had met, I seldom found cause to speak to him, nor he to me. But at one such party he came striding across the room and, interrupting my conversation with Villius and Pasithea, asked abruptly, ‘Where do you live? Is it the house above the harbour? The one with the white walls and tall palms?’

I answered that it was, and at this he nodded and walked off, and I thought no more about it.

But then, next morning, Telamon came to me and said, ‘Marcus, sir. There is a man to see you.’

It was Lucius.

‘I am going to the palaistra,’ he said. ‘I do not like to go alone, and thought you might come.’

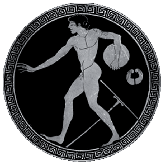

I must have looked at him with surprise. I have never been good at hiding my feelings. I blush when I am angry, and I gape like an idiot when I am shocked. This time, though, I had self-command enough to hide my astonishment with a cough. I knew that Titus, with his liking for Greek things, would occasionally go to the palaistra, with its wrestling-ground and running-tracks and ball courts. But even he went only when his Greek friends invited him.

If you are Roman, you will understand this reticence. At home I had certainly hardened my body, in the normal work of the farm, in hunting, or, more recently, in teaching myself to run and throw the javelin and swing the ancient heavy sword I had found in the outhouse. To all these there was purpose. But to work one’s body as an end in itself, as a sculptor might work clay into a statue, or a potter a fine pot, was still a thing strange to Romans.

But I thought to myself: Titus has set the fashion in Greek manners, and Lucius is following it. It came to me too that this was some sort of peace-offering by Lucius. It would be churlish to refuse, when he had made a special point of coming to my house.