Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers (18 page)

Read Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers Online

Authors: Lillian Faderman

Tags: #Literary Criticism/Gay and Lesbian

A San Francisco “gay girls” bar during World War II. (Courtesy of the June Mazer Lesbian Collection, Los Angeles.)

WAC Sergeant Johnnie Phelps during World War II. General Eisenhower told her to “forget the order” to ferret out the lesbians in her battalion. (Courtesy of Johnnie Phelps.)

On military bases during the 1950s informers were planted on women’s softball teams, since lesbians were thought to be attracted to athletics. (Courtesy of Betty Jetter.)

Beverly Shaw sang “songs tailored to your taste” at elegant lesbian bars in the 1950s. (Courtesy of the June Mazer Lesbian Collection, Los Angeles.)

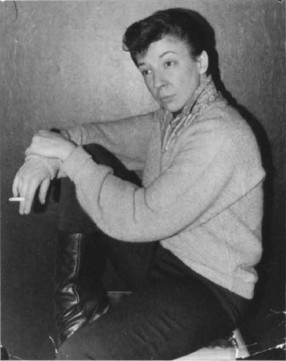

Frankie, a 1950s butch. (Courtesy of Frankie Hucklenbroich.)

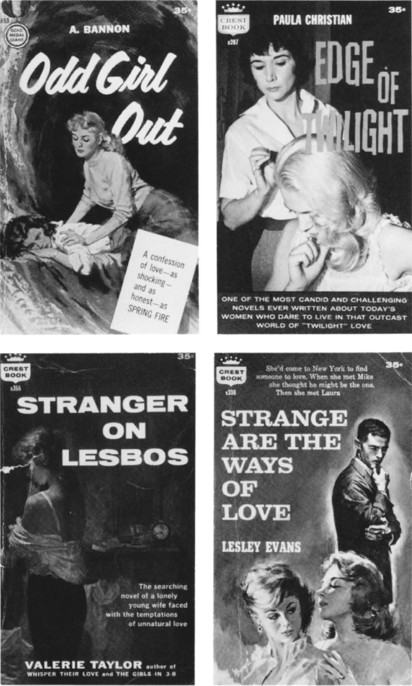

The pulps of the 1950s and ’60s were full of “odd girls” and “twilight lovers.” (Courtesy of Ballantine Books, Inc.)

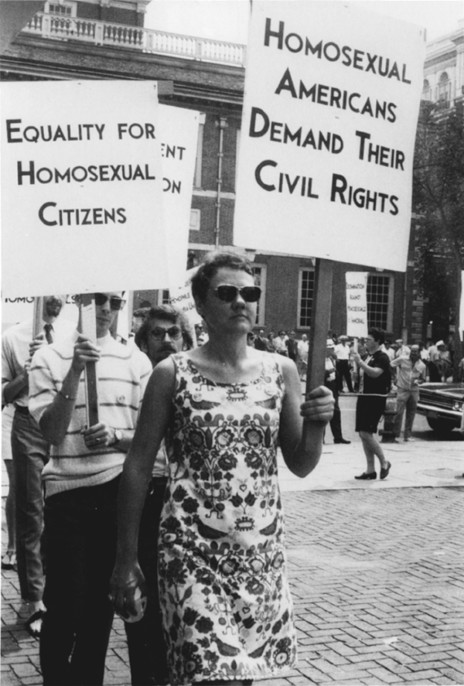

Barbara Gittings in a pre-Stonewall lesbian and gay rights demonstration in front of Independence Hall, Philadelphia. (Courtesy of Nancy Tucker.)

Wastelands and Oases: The 1930s

Lydia to her fiance on leaving a women’s school:

These bunches of women living together, falling in love with each other because they haven’t anyone else to fall in love with! It’s obscene! Oh, take me away!

—

Marion Patton,

Dance on the Tortoise,

1930

I feel confident she is in love with me just as much as I am with her. She is concerned about me and so thoughtful…. My sex life has never caused me any regrets. I’m very much richer by it. I feel it has stimulated me and my imagination and increased my creative powers.

—

32-year-old woman interviewed in 1935

for George Henry’s

Sex Variants

Perhaps if the move toward greater sexual freedom that was barely begun in the 1920s had not been interrupted by the depression, erotic love between women might have been somewhat less stigmatized in public opinion in the 1930s and a lesbian subculture might have developed more rapidly. Instead, whatever fears were generated about love between women in the 1920s were magnified in the uncertainty of the next decade as the economic situation became dismal and Americans were faced with problems of survival. This aborted liberality, together with the narrowing of economic possibilities, necessarily affected a woman’s freedom to live and love as she chose.

While more and more women continued to be made aware of the sexual potential in female same-sex relationships—through the great notoriety of

The Well of Loneliness

and the many works it influenced in the 1930s, through the continued popularity and proliferation of psychoanalytic ideas, and through a persistently though slowly growing lesbian subculture—to live as a lesbian in the 1930s was not a choice for the fainthearted. Not only would a woman have considerable difficulty in supporting herself, but also she would have to brave the increasing hostility toward independent females that intensified in the midst of the depression, and the continued spread of medical opinion regarding the abnormality of love between women. On top of all that, she would need a great spirit of adventure if she hoped to seek out a still-fledgling and well-hidden subculture, or a great self-sufficiency if she could not find it. For all these reasons, few women who loved other women were willing to identify themselves as lesbian in the 1930s. They often married and were largely cut off from other women—imprisoned in their husbands’ homes, where they could choose to renounce their longings or engage only in surreptitious lesbian affairs.

Kinder, Ktiche, Kirche and the “Bisexual” Compromise

Among middle-class women the depression was the great hindrance to a more rapid development of lesbian lifestyles, primarily because it squelched for them the possibility of permanently committing themselves to same-sex relationships. Such arrangements demanded above all that they have some degree of financial independence so that they did not have to marry in order to survive, and financial independence became more problematic for them in the 1930s. It was not that fewer women worked—in fact, the number of working women increased slightly during that decade. It was rather that in tight economic times they were discouraged from competing against men for better paying jobs and most women had to settle for low-salaried, menial jobs that demanded a second income for a modicum of comfort and made the legal permanence of marriage attractive.

Poor women who loved other women had never been led to believe that they might expect more rewarding or remunerative work. Though the depression rendered some of them jobless and homeless, they sometimes managed to make the best of a bad situation. For example, statistics gathered in 1933 estimated that about 150,000 women were wandering around the country as hoboes or “sisters of the road,” as they were called by male hoboes. For young working-class lesbians without work, hobo life could be an adventure. It permitted them to wear pants, as they usually could not back home, and to indulge a passion for wanderlust and excitement that was permitted only to men in easier times. Life on the road also gave them a protective camouflage. They could hitch up with another woman, ostensibly for safety and company, but in reality because they were a lesbian couple, and they could see the world together. Depression historians have suggested that such working-class lesbian couples were not uncommon in the hobo population during the 1930s. The most detailed eyewitness account of lesbian hoboes during the depression is that of a woman who was herself a hobo, Box-Car Bertha, who reported in her autobiography that lesbians on the road usually traveled in small groups and had little difficulty getting rides or obtaining food. She attributes a surprising liberality to motorists, which seems somewhat doubtful considering the general attitudes toward lesbianism that were rampant in America by this time. Bertha claims that “the majority of automobilists” who gave lesbians a ride were not only generous with them but would not think of molesting them physically or verbally: “They sensed [the women] were queer and made very little effort to become familiar.”

1

The hobo lesbians’ middle-class counterparts, who came of age hoping to enjoy the expanded opportunities the earlier decades of the century had seemed to promise, were perhaps less cavalier about the new economic developments. They must often have felt because of the depression that they had to compromise their same-sex affections through a heterosexual marriage if they found a husband who would rescue them from the ignominy of working in a shop or as a lowly office clerk. Such jobs were available to females during the 1930s, since women could be hired for a fraction of men’s salaries. The “careers,” however, which had been giving middle-class women the professional status that so many early feminists had fought for, were now more likely to be reserved for men who “had a family to support.”

2