Octopus (17 page)

Authors: Roland C. Anderson

We don't yet understand why the mimic octopus has such ostentatious behaviors. Scientists speculate that this octopus mimics other animals that a predator wouldn't want to eatâan aposematism, when an animal imitates or looks like another that tastes bad or is venomous. If the mimic octopus can resemble the poisonous Moses sole, a stinging jellyfish that no fish would want to eat, and even a frilly venomous lionfish, then surely the normal octopus predators, such as grouper or barracuda, would avoid it.

This apparent mimicry behavior is also common in other shallow-water octopuses and a few deep-water species of octopus. Several widely scattered tropical species can make the same body patterns as the mimic octopus. An undescribed species in Hawaii does it. We have seen the Atlantic long-arm octopus do it in the Caribbean waters of Bonaire: it flattened itself and cruised over the sand just like a sole. We shall no doubt discover more unusual behaviors among tropical octopuses as they are observed more in detail. The tropical, shallow-water, Indo-Pacific octopuses are particularly likely subjects for future discoveries.

If camouflage, hiding, frightening, inking, bluffing, or blowing water

jets at a predator do not confuse or scare it off, the octopus may have to fight for its life. If the intelligent octopus's home range has many predators, it may move away to a different area, which isn't a problem for octopuses since they don't hold territories and don't spend much time in any one den. Jim Cosgrove and Neil McDaniel (2009) found that giant Pacific octopuses only live in any one den about a month before moving on. Octopuses do move on if predators are directly annoying them, or if a scientist forces them out with noxious chemicals. If an octopus survives an attack such as by a moray eel that comes right into its den, it doesn't go back to that den. The lack of attachment to a particular den is good for the octopus but hard on the researcher who wants to study the animal.

A Bad Bite

Humans sometimes get bitten by octopuses, which is, after all, simply defense on the part of the octopus. One day, a Seattle Aquarium employee was leading a beach tour at Saltwater State Park just south of Seattle on Puget Sound. Nearby scuba divers had caught a red octopus, which they brought to shore and placed in a bucket to show to the group. As the aquarium employee handled the octopus properly with a gloved hand, it abruptly bit him on his wrist just above the glove. He didn't notice the bite at first because there was no pain.

About a minute later, he noticed blood and saw the bite wound. The small puncture was less than in. (3 mm) wide, which is the size for a bite from a small octopus with a body 1 in. (2.5 cm) long. When he noticed the bite, he sucked on the wound to extract the venom, but this didn't do much good. After about ten minutes, the wound site began to hurt. When swelling and fiery pain began to extend up his forearm, he called the aquarium on his cellular phone.

in. (3 mm) wide, which is the size for a bite from a small octopus with a body 1 in. (2.5 cm) long. When he noticed the bite, he sucked on the wound to extract the venom, but this didn't do much good. After about ten minutes, the wound site began to hurt. When swelling and fiery pain began to extend up his forearm, he called the aquarium on his cellular phone.

Other aquarium employees suggested immersing the wound in hot water, as hot as he could stand. A nearby espresso stand supplied the hot water. About 20 minutes after the bite occurred, he poured this water directly over the wound and the adjacent area. The pain and swelling from the bite dissipated within a minute, but he still went to Harborview Hospital in Seattle, the area's main trauma care center. The hospital notified the aquarium to get advice on the treatment of an octopus bite, and a nurse then applied an ointment for the blisters caused by the hot water. The next day, the bite could scarcely be seen or felt, but the man had headaches and weakness for a week. This man was lucky. An untreated bite from a red octopus on an aquarium employee twenty-five years earlier left rotting flesh at the site for about a month and a deep scar.

âRoland C. Anderson

If an octopus is bitten by a predator or is forced to fight, it still has two methods of remaining aliveâone passive and one quite aggressive. If an octopus is held by one of its arms, it may detach the attacked arm. If a fish or marine mammal bites off an arm, the octopus can swim away minus the arm.

Some species of octopus have a set area in their arms close to the body where there is a narrowing or stricture. These speciesâthe banded string-arm octopus (Ameloctopus litoralis), for exampleâare relatively small and have long, snaky arms. They have developed the ability to autotomize, or cast off a limb when attacked by a predator. Supposedly, the predator will take the limb instead of the octopus, and will be kept occupied long enough for the octopus to escape.

If the octopus is facing a major threat from a predator, it can bite whatever is molesting it with its beak. A piercing bite from the hard, chitinous, parrotlike beak of an octopus can be a serious deterrent to predators. The beak is well-muscled and has flanges for muscle attachments and leverage. When an octopus bites because of a threat, it can also inject poisonous venom into the wound.

Octopuses don't always avoid being eaten, of course, especially by humans. For millennia, octopus has been a favored food among peoples of the world. And today, thousands of tons of octopuses are harvested each year for human consumption, primarily in Europe, Asia, and the tropical Indo-Pacific. So the octopus doesn't always win in the game of “eat or be eaten.”

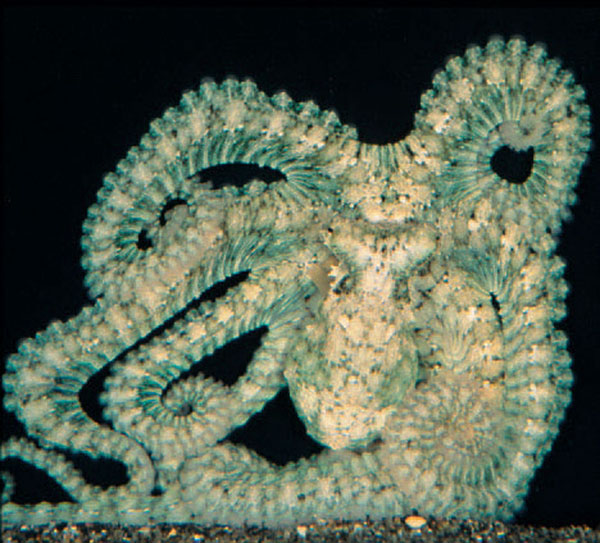

Plate 1.

This view of

Octopus abaculus

reveals the eight arms, the head, and the saclike mantle. Roy Caldwell.

Plate 2.

This octopus, known as wunderpus (

Wunderpus photogenicus

), only recently named by scientists, shows that not all species use background-matching camouflage. This species is thought to mimic toxic or venomous creatures. Roy Caldwell.

Plate 3.

The bright appearance of the circular areas on the skin of this blue-ringed octopus (

Hapalochlaena maculosa

) shows its warning coloration, which advertises that the animal has a deadly venomous bite. Roy Caldwell.

Plate 4.

These small and large octopus eggs from the sibling species of two-spot octopus, Verrill's two-spot octopus (

Octopus bimaculatus

) above and Californian two-spot octopus (

O. bimaculoides

) below, give an idea of the species' relative size. John Forsythe.

Plate 5.

This female red octopus (

Octopus rubescens

) is faithfully tending her eggs. Seattle Aquarium.