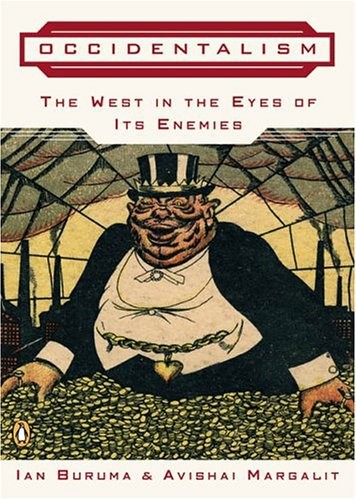

Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

Read Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies Online

Authors: Ian Buruma,Avishai Margalit

Tags: #History, #World, #Political Science, #International Relations, #General

BOOK: Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

8.53Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

[ALSO BY IAN BURUMA]

Inventing Japan, 1853-1964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Playing the Game

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers, Transvestites,

Gangsters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

Gangsters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

[ALSO BY AVISHAI MARGALIT]

The Ethics of Memory

Views and Reviews: Politics and Culture in the State of the Jews

The Decent Society

Idolatry

(with Moshe Halbertal )

(with Moshe Halbertal )

THE PENGUIN PRESS

a member of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

a member of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

All rights reserved

Portions of this book appeared in different form in an essay entitled “Occidentalism,”

The New York Review of Books,

January 17, 2002.

The New York Review of Books,

January 17, 2002.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from “Choruses

from ‘The Rock’ ” from

Collected Poems 1909-1962

by T. S. Eliot. Copyright 1936

by Harcourt, Inc. Copyright © 1964, 1963 by T. S. Eliot.

, and Faber and Faber.

from ‘The Rock’ ” from

Collected Poems 1909-1962

by T. S. Eliot. Copyright 1936

by Harcourt, Inc. Copyright © 1964, 1963 by T. S. Eliot.

, and Faber and Faber.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Buruma, Ian.

Occidentalism : the West in the eyes of its enemies /

Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit.

p. cm.

Includes index.

Occidentalism : the West in the eyes of its enemies /

Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit.

p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN : 978-1-101-09941-4

1. Civilization, Western. 2. Developing countries—

Civilization—Western influences.

I. Margalit, Avishai, 1939- II. Title.

CB245.B

303.48’172401821—dc22

Civilization—Western influences.

I. Margalit, Avishai, 1939- II. Title.

CB245.B

303.48’172401821—dc22

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Robert B. Silvers

[WAR AGAINST THE WEST]

I

N JULY 1942, JUST SEVEN MONTHS AFTER THE JAPANESE bombed the American fleet in Pearl Harbor and overwhelmed the Western powers in Southeast Asia, a number of distinguished Japanese scholars and intellectuals gathered for a conference in Kyoto. Some were literati of the so-called Romantic Group; others were philosophers of the Buddhist/ Hegelian Kyoto School. Their topic of discussion was “how to overcome the modern.”

1

N JULY 1942, JUST SEVEN MONTHS AFTER THE JAPANESE bombed the American fleet in Pearl Harbor and overwhelmed the Western powers in Southeast Asia, a number of distinguished Japanese scholars and intellectuals gathered for a conference in Kyoto. Some were literati of the so-called Romantic Group; others were philosophers of the Buddhist/ Hegelian Kyoto School. Their topic of discussion was “how to overcome the modern.”

1

It was a time of nationalist zeal, and the intellectuals who attended the conference were all nationalists in one way or another, but oddly enough the war itself, in China, Hawaii, or Southeast Asia, was barely mentioned. At least one of those attending, Hayashi Fusao, a former Marxist turned ardent nationalist, later wrote that the assault on the West had filled him with jubilation. Even though he was in freezing Manchuria when he heard the news, it felt as though dark clouds had lifted to reveal a clear summer sky. No doubt similar emotions came over many of his colleagues. But war propaganda was not the ostensible point of the conference. These men—the literary romantics, as much as the philosophers—had been interested in overcoming the modern long before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Their conclusions, to the extent that they had enough coherence to be politically useful, lent themselves to propaganda for a new Asian Order under Japanese leadership, but the intellectuals would have been horrified to be called propagandists. They were thinkers, not hacks.

“The modern” is in any case a slippery concept. In Kyoto in 1942, as in Kabul or Karachi in 2001, it meant the West. But the West is almost as elusive as the modern. Japanese intellectuals had strong feelings about what they were against, but had some difficulty defining exactly what that was. Westernization, one opined, was like a disease that had infected the Japanese spirit. The “modern thing,” said another, was a “European thing.” There was much talk about unhealthy specialization in knowledge, which had splintered the wholeness of Oriental spiritual culture. Science was to blame. And so were capitalism, and the absorption into Japanese society of modern technology, and notions of individual freedoms and democracy. All these had to be “overcome.” A film critic named Tsumura Hideo excoriated Hollywood movies and praised the documentary films of Leni Riefenstahl about Nazi rallies, which were more in tune with his ideas about how to forge a strong national community. In his view, the war against the West was a war against the “poisonous materialist civilization” built on Jewish financial capitalist power. All agreed that culture—that is, traditional Japanese culture—was spiritual and profound, whereas modern Western civilization was shallow, rootless, and destructive of creative power. The West, particularly the United States, was coldly mechanical. A holistic, traditional Orient united under divine Japanese imperial rule would restore the warm organic community to spiritual health. As one of the participants put it, the struggle was between Japanese blood and Western intellect.

The West, to Asians at that time, and to some extent still today, also meant colonialism. Since the nineteenth century, when China was humiliated in the Opium War, educated Japanese realized that national survival depended on careful study and emulation of the ideas and technology that gave the Western colonial powers their advantages. Never had a great nation embarked on such a radical transformation as Japan between the 1850s and the 1910s. The main slogan of the Meiji period (1868-1912) was

Bunmei Kaika,

or Civilization and Enlightenment—that is, Western civilization and enlightenment. Everything Western, from natural science to literary realism, was hungrily soaked up by Japanese intellectuals. European dress, Prussian constitutional law, British naval strategies, German philosophy, American cinema, French architecture, and much, much more were taken over and adapted.

Bunmei Kaika,

or Civilization and Enlightenment—that is, Western civilization and enlightenment. Everything Western, from natural science to literary realism, was hungrily soaked up by Japanese intellectuals. European dress, Prussian constitutional law, British naval strategies, German philosophy, American cinema, French architecture, and much, much more were taken over and adapted.

The transformation paid off handsomely. Japan remained uncolonized and quickly became a great power, one that managed, in 1905, to defeat Russia in a thoroughly modern war. Indeed, Tolstoy described the Japanese victory as a triumph of Western materialism over Russia’s Asiatic soul. But there were disadvantages. Japan’s industrial revolution, which came not long after Germany’s, had equally dislocating effects. Large numbers of impoverished country people moved into the cities, where conditions could be cruel. The army was a brutal refuge for rural young men, and their sisters sometimes had to be sold to big-city brothels. But economic problems aside, there was another reason many Japanese intellectuals sought to undo the wholesale Westernization of the late nineteenth century. It was as though Japan suffered from intellectual indigestion. Western civilization had been swallowed too fast. And this is partly why that group of literati gathered in Kyoto to discuss ways of reversing history, overcoming the West, and being modern while at the same time returning to an idealized spiritual past.

None of this would be of more than historical interest if such ideals had lost their inspirational power. But they have not. The loathing of everything people associate with the Western world, exemplified by America, is still strong, though no longer primarily in Japan. It attracts radical Muslims to a politicized Islamic ideology in which the United States features as the devil incarnate. It is shared by extreme nationalists in China, and other parts of the non-Western world. And strains of it also crop up in the thinking of radical anticapitalists in the West itself. To call it either right- or left-wing would be misleading. The desire to overcome Western modernity in 1930s Japan was as strong among some Marxist intellectuals as it was in right-wing chauvinist circles. The same tendency can be observed to this day.

Of course, different people have different reasons for hating the West. We cannot simply lump leftist enemies of “U.S. imperialism” together with Islamist radicals. Both groups might hate the global reach of American culture and corporate power, but their political goals cannot be usefully compared. Just so, Romantic poets might yearn for a pastoral arcadia and detest the modern, commercial metropolis, but this does not mean they have anything else in common with religious radicals who seek to establish God’s kingdom on earth. A distaste for some aspects of modern Western, or American, culture is shared by many, but this is only rarely translated into revolutionary violence. Symptoms become interesting only when they develop into a full-blown disease. Not liking Western pop culture, global capitalism, U.S. foreign policy, big cities, or sexual license is not of great moment; the desire to declare a war on the West for such a reason is.

The dehumanizing picture of the West painted by its enemies is what we have called Occidentalism. It is our intention in this book to examine this cluster of prejudices and trace their historical roots. That they cannot be explained simply as a peculiar Islamic problem is clear. Much has gone terribly wrong in the Muslim world, but Occidentalism cannot be reduced to a Middle Eastern sickness any more than it could to a specifically Japanese disease more than fifty years ago. Even to use such medical terminology is to fall into a noxious rhetorical habit of the Occidentalists themselves. It is indeed one of our contentions that Occidentalism, like capitalism, Marxism, and many other modern isms, was born in Europe, before it was transferred to other parts of the world. The West was the source of the Enlightenment and its secular, liberal offshoots, but also of its frequently poisonous antidotes. In a way, Occidentalism can be compared to those colorful textiles exported from France to Tahiti, where they were adopted as native dress, only to be depicted by Gauguin and others as a typical example of tropical exoticism.

To define the historical context of Western modernity and its hateful caricature, Occidentalism, is not a simple matter, as the arguments among the Kyoto intellectuals showed. There are too many links and overlaps to establish perfect coherence. The philosopher Nishitani Keiji blamed the religious Reformation, the Renaissance, and the emergence of natural science for the destruction of a unified spiritual culture in Europe. This gets to the core of Occidentalism. It is often said that one of the basic distinctions between the modern West and the Islamic world is the separation of church and state. The church, as a distinct institution, did not exist in Islam. To a devout Muslim, politics, economics, science, and religion cannot be split into separate categories. But the professor in Kyoto was not a Muslim, and his ideal was also to build a state in which politics and religion formed a seamless whole, and the church, as it were, merged with the state. That church in wartime Japan was State Shinto, a modern invention, based less on ancient Japanese tradition than on a peculiar interpretation of the pre-modern West. The Japanese tried to reinvent a distorted idea of medieval Christian Europe by turning Shinto into a politicized church. This type of spiritual politics is to be found in all forms of Occidentalism, from Kyoto in the 1930s to Tehran in the 1970s. It is also an essential component of totalitarianism. Every institution in Hitler’s Third Reich, from the churches to the science departments of universities, had to be made to conform with a totalist vision. The same was true of the Soviet Union under Stalin and of Mao’s China.

Other books

My Beloved World by Sonia Sotomayor

Teresa Medeiros by Breath of Magic

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

The Sweet Dreams Bake Shop (A Sweet Cove Mystery Book 1) by J A Whiting

The Children Act by Ian McEwan

The Machiavelli Covenant by Allan Folsom

The Last Days by Laurent Seksik

Logan's Redemption by Cara Marsi

Marriage Made on Paper by Maisey Yates