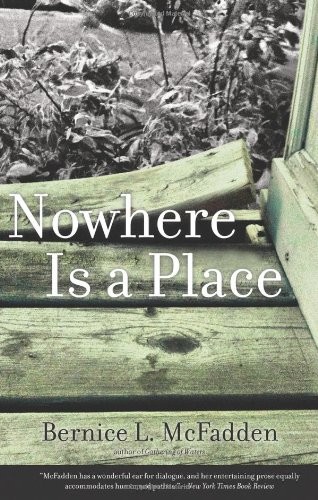

Nowhere Is a Place

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, as well as events or locales, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

Originally published in hardcover by Dutton in 2006

©2006, 2013 by Bernice L. McFadden

ISBN-13: 978-1-61775-131-8

eISBN: 9781617751523

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939272

All Rights Reserved.

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

[email protected]

www.akashicbooks.com

Table of Contents

Bonus Material:

Gathering of Waters

Excerpt

For my daddy

Robert Lewis McFadden

July 22, 1942–January 14, 2005

I miss you

Acknowledgments

Gratitude . . .

My family

My friends

My readers

My spirits

My Creator

The present contains nothing more than the past,

and what is found in the effect was already in the cause.

—Henri Louis Bergson

i was torn from my somewhere and brought to this nowhere place

i felt alone in this land that was nowhere from my everywhere.

i didn’t understand the tongue

i didn’t understand the tongue

i didn’t understand the tongue and why it was the trees here bore

strange fruit that watched me with dead eyes

cruel hands

cruel hands

cruel hands, tied me down, strung me up, dug into me, and sold off

what came out of me

time flowed on like the river

like the river, time flowed on, but i held tight to the memories of my

someplace, refusing to believe that my everywhere had always been

here in this nowhere place.

Smooth Heels

Santa Rey Obius, Mexico

Sherry

Edison Powell, all confidence with a smile that revealed glittering white teeth. Mahogany eyes that sparkled and long piano-playing fingers.

Jazz standards were his favorite

They’d first met over the music, Count Basie’s “Going to Chicago Blues” spilling out from beneath his fingers, her eyes dead set on his jaw, not blinking, not wanting to miss the clench and unclench of it or the sudden toss of his head.

“Curiosity killed the cat,” she murmured into her third glass of chardonnay, after her girlfriends caught her staring at his clenching and unclenching jaw, and the way she trembled when he tossed his head was a dead giveaway that she was more than interested.

Her friend whispered to her from behind cupped palms, egged her on, dared her, prodded her forward with their goading until she found herself almost at his elbow, sandwiched between two women who smelled of vodka and Chanel.

He was on to “Kansas City Keys,” and Sherry was bobbing her head to the music and wondering what it would be like to have those piano-playing fingers dancing across her rib cage and down her spine and then wondering why it was she was wondering such a thing.

The crowd hollered for more, but brunet eyes shook his head no and then turned toward his audience and graciously bowed his head into praying hands before smiling and turning to where Sherry swayed between the vodka- and Chanel-smelling women.

They rushed him, the women with their Colgate-white teeth ruined by tracks of red lipstick, thrusting cosmetically altered breasts in his face while simultaneously presenting him with delicate hands, perfectly manicured fingernails, and diamond-laced wrists. He nodded at them, but kept his own hands folded behind his back.

He nodded and smiled at their compliments, favored them with his smooth talk, electric smile, and brunet-colored eyes, but would not let them touch his piano-playing fingers; those he kept hidden behind his back, stuffed into the wells of his pants pockets, or laced together and swaying in front of his crotch.

“Do you know ‘Cherry Point’?” was all Sherry said to him when he was finally able to break away from the women and was sliding past her.

“‘Cherry Point,’” she said again when all he did was stare.

“Yes,” smooth as silk sailed out of his mouth and then a smile and a nod of his head. He watched her for a while, before he said yes to something else and then turned and started back toward the piano, brushing past the women and their frozen smiles and settling himself down onto his bench.

He positioned his piano-playing fingers over the black-and-white keys, spoke to them with his mind, wiggled them, and then dropped them down and began to play “Cherry Point,” twice.

Later, after his piano-playing fingers played “Avenue C” and “Blue Room Jump” and “April in Paris” down her spine and across her rib cage; after he treated her nipples like the lip of a trumpet, played her ass like a djembe drum, and stroked the inner parts of her thighs like a sitar until the muscles went soft like cream and gave way, her legs parted until they were flung wide, revealing her very own Cherry Point.

And it wasn’t until he lay sleeping beside her, his arm thrown across her breasts, that she realized that his eyes were the same color as her nipples. She realized as the sun broke through the slats of the miniblinds that he had used Count Basie to seduce her and that the clenching and unclenching jaw had reminded her of the pro ball players that mesmerized her and that the toss of his head made her think of easier times and that all of that and the chardonnay had somehow blinded her to the fact that he wasn’t just a man, but a white man.

* * *

It was as easy as pie to get on a plane and fly from St. Louis to Paradise, Nevada, to tell her mother, Dumpling, that she was moving to Chicago—moving into a one-bedroom overlooking the river with her friend, her boyfriend, Edison Powell, the musician with mahogany-colored eyes and piano-playing fingers.

Dumpling had nodded and grunted before finally looking real hard at the picture of the boyfriend who couldn’t find the time to get on the plane with her daughter and meet her face-to-face.

Blond hair, brown eyes. White boy. Sherry hadn’t said a word about that part of him.

“He knows all of Count Basie and can play most anything,” Sherry had gushed.

‘‘You too, it seems,” Dumpling huffed, and handed the picture back to Sherry. “If your daddy were alive, you know he’d disapprove,” she added, hard toned.

Sherry ignored the words. How could Dumpling know what those fingers did to her?

And if her father were alive, he wouldn’t have understood it either; he was a diehard Howling Wolf and Muddy Waters man. But he was dead and buried, ten years by then, that’s why it was easy as pie to hop on that plane from St. Louis to Paradise, Nevada, and announce the plans for the rest of her life in Chicago, with a white man.

“He’s the blackest white boy I’ve ever met,” Sherry said brightly. “Not like those white folks you thinking about at all, Dumpling.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Cool and laid back. He understands the struggle—”

“Whose struggle?”

“Oh, Dumpling, I can’t help who I love.”

“You never have been able to.”

“What does that mean?”

“You always choose wrong; that boy with the lisp from where was it now?”

“Manuel from South America.”

“Yeah, and the other one with the slanted eyes.”

“Mahain.”

“And the one with the turban.”

“Mohammed.”

“I told you none of them would last, didn’t I?”

“You taught me to see people for who they are on the inside.”

“Yes, I did.”

“Well, that’s what I’m doing.”

“So you been seeing this man for how long?”

“Three months.”

“And you think you know his heart?”

“You and Daddy got married in less than two months. Why is this different?”

“Your daddy was black.”

“And?”

“I know’d his heart from before I even know’d him.”

“How is that possible?”

“All us black people here in America got the same heart. We come from the same place.”

“Africa?”

“After that.”

“What are you talking about, Dumpling? Do you mean the South?”

“I’m talking ’bout a place called survival.”

“I’m well aware of our history, Dumpling. It’s not like I went out looking for a white man—”

“Nah, he came looking for you. That’s what they do.”

“White people marched alongside blacks for civil rights.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Okay, Dumpling, whatever you say. I was hoping that you would be happy for me and—”

“Okay, let me ask you this: did you choose him or did he pick you?”

“What?”

“Did you choose or did he pick?”

“I don’t know what—”

“White folks been picking niggers for years. Picking them off, picking them clean—”

“Stop it!”

* * *

Almost eight years and few words passed between Sherry and Dumpling. They had two strikes between them, so Sherry kept her distance to ward off the third strike that she knew would disconnect them forever.

Almost eight years passed before Sherry realized that she preferred the down-home blues—the hip-swaying, countrified blues—to the complex jazz standards.

Almost eight years, and Edison had only slipped and called her a nigger once.

She’d been in no hurry to forgive him for it, but he’d apologized profusely—and had cried and played Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” over and over again on his piano before she let him back into their bedroom.

A year after that, his piano-playing fingers came down across her face and sent her reeling. Not as far as the slap her mother had levied across her face thirty-two years earlier; though she would realize later on that both slaps had centuries behind them.

Sherry was just six years old on that day when she sat curled up in her Uncle Beanie Moe’s lap, one arm slung across his neck, the other fingering the string of blue beads he’d brought her back from New Orleans.

Her mother, Dumpling, had walked into the room smiling, then stopped and stared as the smile froze and cracked on her face. Sherry couldn’t have known that her sitting innocently on her uncle’s knee would hurtle her mother back in time—back to a warm Easter afternoon when a misplaced hand had suddenly turned ugly.

Dumpling’s eyes went glassy as she marched over to them, lifted her hand into the air, and brought it down across Sherry’s six-year-old face so hard, the girl had ended up kissing the floor and seeing stars.

Dumpling had never said why she slapped Sherry, and Beanie Moe hadn’t asked. He just helped Sherry up and carried her over to the couch and sat her down. He comforted her with words, but didn’t dare touch her.

Dumpling, she just stormed out of the room, leaving the slight scent of Ivory soap swirling in the air.

Years later, Edison hadn’t even missed a beat. His hand back at his side and shaking as he continued to holler and hurl cuss words at her.

She, Sherry, was sprawled across the floor, stunned, her hand cradling the place on her cheek that was stinging and throbbing. And then his hands were up in the air, flailing as he stormed like a madman between the bedroom and the living room, calling her every kind of bitch she could ever imagine, and then the toe of his shoe made contact with her thigh, giving her hand purpose and hurtling her mind further toward amazement—its brilliance so dazzling, she was forced to squint.