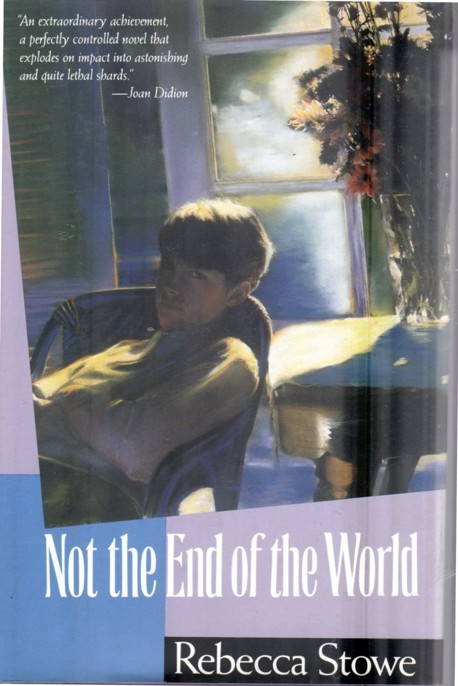

Not the End of the World

Read Not the End of the World Online

Authors: Rebecca Stowe

Tags: #Fiction, #Family Life, #Literary, #Coming of Age

Copyright © 1991 by Rebecca Stowe

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Peter Owen Ltd., London in 1991.

“Two Years Later” from

The Poems of W. B. Yeats: A New Edition

edited by Richard J. Finneran (New York: Macmillan, 1983)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stowe, Rebecca.

Not the end of the world / Rebecca Stowe.

I. Title.

PS3569.T6753N67 1992 813′.54—dc20 91-53084

eISBN: 978-0-307-83216-0

v3.1

Has no one said those daring

Kind eyes should be more learn’d?

Or warned you how despairing

The moths are when they are burned?

I could have warned you; but you are young,

So we speak a different tongue.

O you will take whatever’s offered

And dream that all the world’s a friend,

Suffer as your mother suffered,

Be as broken in the end.

But I am old and you are young.

And I speak a barbarous tongue.

W B. Yeats, “Two Years Later”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

About the Author

“A man,” I said when Miss Nolan asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up.

The Bridge Ladies tittered like a bunch of fat little birds.

“She’s crazy,” Grandmother said and clicked her tongue and wanted to know if any of the Bridge Ladies had ever seen such a sullen little thing. “She says she wants to be the first woman governor of Michigan,” she cackled as she began pulling at her cards with her red-tipped fingers. “Can you imagine? Whoever heard of such a thing?”

The Bridge Ladies tittered some more and Miss Nolan peered at me over her cards, the tip of her white rubber nose peeking over the pansies, and pointed out that I couldn’t be the first woman governor of Michigan if I were a man.

“You didn’t ask what I was

going

to be. You asked what I

wanted

to be.”

Mother gasped and Grandmother glared but Miss Nolan just laughed. “I think perhaps you’re too honest to be a politician, Maggie,” she said, lowering her cards and revealing

her white rubber nose in all its grotesqueness. “You’ll have to learn some diplomacy.”

I blushed and hung my head, angry with myself for not being able to look at her, to look at the repulsive white thing stuck on her face like a plastic Mr. Potato-Head part. Grandmother always used Miss Nolan as an Example. “That’s what will happen to you,” she’d threaten, chasing me around the house with a tube of sunscreen, shaking it at me and saying, “All right, Miss Smarty-Pants, just don’t come crying to me when you have to have your nose removed.”

Mrs. Tucker snorted. “Pee-pee envy,” she said knowingly and the Bridge Ladies shrieked like crows.

“May I go now, please?” I asked, thinking I’d die if I had to stand there one more second, being polite while Grandmother insulted me and Mrs. Tucker made snide remarks.

“And where are

you

off to, Miss Ants-in-the-Pants?”

That was Mother. When Grandmother was around, I couldn’t tell them apart, they were always insulting me and calling me stupid names, names so stupid even my friends didn’t use them. Miss Ants-in-the-Pants! What was I, three?

“The beach,” I said and Mrs. Tucker said I should call Cindy; she didn’t think Cindy was doing anything after her guitar lesson. Or perhaps she was. Maybe she had ballet. Or maybe she was going water skiing in Rick Keller’s boat. She just couldn’t keep up with her. Why didn’t I have any Outside Activities? Outside Activities build character. Cindy had plenty of

that!

I shrugged and said I thought I’d like to be alone. They all laughed and Grandmother fanned herself with her cards and made heaving noises.

“She thinks she’s Greta Garbo,” she said. “Whoever heard of such a thing? A twelve-year-old who

vants to be a-lone?”

They laughed some more and Mother informed them I had a paper to do for summer school.

“Summer school!” Miss Nolan said. “Why, Maggie, I had no idea you were so dedicated a scholar.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I’m being punished.”

“Oh,” Miss Nolan said, blushing a bright red ring around her rubber nose, “I’m so sorry!”

Not half as sorry as I was, I thought, wishing Mother would dismiss me so I could run to the beach and hide. I felt like a prisoner, having to stand around while my executioners had a quick game of cards before taking me out back to stand me against the picnic table and shoot me.

They lit cigarettes and arranged their cards, as if I weren’t there, as if I hadn’t asked to be dismissed, as if I were just an invisible vapor they only paid attention to when they needed something to laugh at. Grandmother was glaring across the table, angrily watching Mother lay out her dummy hand, as if it were Mother’s fault she didn’t have the cards Grandmother wanted. She’d yell at her later, when the Bridge Ladies had left and before Daddy came home; she’d scream at her for not having bid correctly, for having given her the wrong clues.

“May I go now?” I asked again and Mother nodded glumly as the Bridge Ladies smiled fake smiles and smoked and slapped their cards on the table. “C’mon, Goob,” I shouted and she bounced out from under the couch and we flew out the door. “I hate them,” I told Goober, “I hate them.” I loathed them, despised them, wished they’d all step on rusty nails and get lockjaw It would serve them right.

Here it was, almost the end of the world, and all they did was sit around smoking cigarettes and drinking martinis and playing bridge with a deck of pansied cards when at any minute the whole world could be blown up into a zillion pieces. People were building bombshelters and storing cans of fruit and choosing the people they’d take with them into their safe little caves, the people who would survive the

atomic blast and create a new world, and all these stupid women could think about was building character through ballet. Character, schmaracter. What difference did it make if you were dead? What difference did it make, anyway? You built up character all the time you were a kid and as soon as you were an adult, you tossed it out the back door with the coffee grounds.

Well, pretty soon they’d be singing a different tune. Pretty soon, they’d all be fried and not just their noses, but everything, right down to their toenails. They’d be sizzled like hot dogs on a grill, sputtering and popping and bursting their seams.

“I wish we could move to Oregon,” I told Goober as we crawled under the shrubs overlooking the breakwall, to check to see if any Enemies were on the sand, sunbathing. Oregon was the only state that might not get zapped, but my parents wouldn’t move. They thought I was crazy.

“Margaret, where do you come up with these ideas?” Mother would moan when I’d show up at the dinner table with a list of essentials for surviving the atomic blast. “School,” I’d say and she’d wonder why, if that were the case, no one else’s children were making such a fuss about it. I’d shrug and look to Donald for support, but he was too busy thinking about getting dinner over so he could hide in his room with his stupid girlie magazines to care about the end of the world. I hated those magazines, with the bare naked ladies grinning at the camera and their boobies hanging out in public; it was disgusting and I wish I’d never found them in between Donald’s mattresses.

Donald and I used to be best friends until he became a teenager. We still stuck together when we had to do “family” things, but outside the house he pretended like he didn’t know me. “Right, Donald?” I’d say and kick him under the

table, but he’d just grunt. Ruthie would start squawking and crying, certain that when the Bomb hit, Mother and Daddy would take Donald and me away, leaving her to fry alone. “You’re going to

leave

me!” she’d sob. “The Russians are going to get me!” I’d grab her pudgy little arm and tell her to knock it off. “The Russians don’t care about

you,”

I’d say and then she’d really start sobbing. “Nobody loves me!” she’d wail. “Nobody wants me!” She’d flap her arms and drift off into her little birdworld, squawking and screeching and pecking at her plate with her nose. “Now look what you’ve done,” Mother would say, shoving a plate at me. “You’ve set her off again.” “Me?” I’d scream. “Why is it always

me? I’m

not the one putting missiles in Cuba!” Then Daddy would try to demand peace—he’d thump his fist on the table and stare at me and tell me that was enough. He’d call me “Young Lady” and that would set

me

off. “Don’t

call

me that!” I’d shriek and run from the table, through the kitchen and up the stairs. I’d lock myself in the bathroom, waiting for the All-Clear, waiting for someone to come and tell me everything was OK, I could come out now, it’s not the end of the world.

But it never happened.

O

NLY

Mrs. Prittle, the neighborhood spy, was at the beach, sitting in her red and white striped beach chair like a leather vulture, waiting to pounce on anyone who ventured down the steps to the sand and to chase off anyone who didn’t belong at Edison Beach.

I didn’t want her to see me; if she did I’d have to go over and be polite, and being polite was what I hated third in the world. Mrs. Prittle asked too many questions—she was always poking and prying and even though she was just trying to be nice, to make conversation, it drove me crazy because I always ended up telling her things I didn’t want to tell her, just because she was so pushy. She meant well, I guess, but she made me all squirmy.

She didn’t have any kids of her own, just a snappy, hairy dog with some Chinese name, Ping-Pong or something. After the Red Chinese started threatening to take over the world, she told everybody the dog was

really

Japanese, like she was afraid people would think it was a spy.

The only way to avoid her was to crawl through the shrubs to the Kellers’ hedge and then slide down the sand onto their beach and then sneak across the Wilsons’ beach to the Sisks’. The Sisks’ beach was my private hideaway, cut off by two high and long cement breakwalls, extending all the way into the water so nobody could walk on their beach. The Sisks never used their beach and if they came out at all, it was to sit in their pretty white gazebo, set up on a little lump of a hill, separated from the beach by a row of stumpy evergreens. They could sit up there and watch the freighters chugging past without getting sand in their shoes.