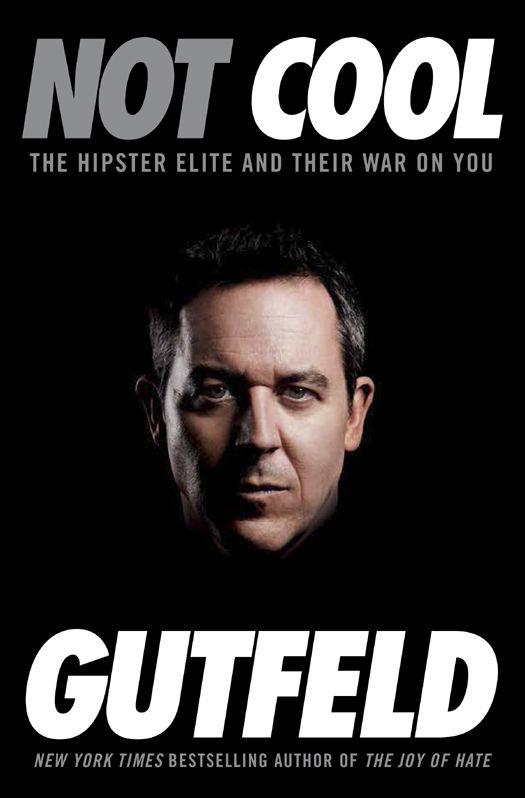

Not Cool: The Hipster Elite and Their War on You

Read Not Cool: The Hipster Elite and Their War on You Online

Authors: Greg Gutfeld

Tags: #Humor, #Topic, #Political, #Biography & Autobiography, #Political Science, #Essays

T

HE

J

OY OF

H

ATE

How to Triumph over Whiners in the Age of Phony Outrage

T

HE

B

IBLE OF

U

NSPEAKABLE

T

RUTHS

L

ESSONS FROM THE

L

AND OF

P

ORK

S

CRATCHING

T

HE

S

CORECARD

Copyright © 2014 by Greg Gutfeld

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Forum,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House LLC,

a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

.

CROWN FORUM with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gutfeld, Greg.

Not cool : the hipster elite and their war on you / Greg Gutfeld.

pages cm

1. Conduct of life—Humor. 2. Elite (Social sciences)—Humor. I. Title.

PN6231.C6142G88 2014

818′.602—dc23 2013050828

ISBN 978-0-8041-3853-6

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-3854-3

Jacket design by Michael Nagin

Jacket photograph by Mark Mann

v3.1

To Jackie and Elena

-CONTENTS

The longer I live, the more I’m convinced the world’s just one big high school, with the cool kids always targeting the uncool.

—M

E

,

The Joy of Hate

, November 2012

Yes, I just quoted myself. Someone has to. But that quote also explains every thought I have about our existence on this silly orb called earth. The world is a high school, only more cruel, more reckless, and certainly more expensive. The lockers became apartments, the teachers our bosses, the guidance counselors our bartenders. Gym class has been replaced by health clubs, with Pilates now a substitute for climbing that horrible, horrible rope. The bathroom wall—a stinky billboard where grubby teens etched limericks and crude boobs—has morphed into the anonymous world of message boards, populated by cruder boobs.

Who runs the high school we all live in? The cool: people who consider themselves rebels and tastemakers for all that’s edgy. They are now in control of defining the “conversation”—of deeming what is good and what is bad. Their power is drawn from their self-appointed cool—and a world that gladly forfeited character for an illusion of it. But it’s all BS. In fact, if you scratch the surface of their cool veneer, you’ll find that they’re about as counterculture as a toupee, and not even remotely as useful.

My mission here is to provide the remedy to this vast world of pretension, envy, and hate, to write the guidebook on how to deal

with the bullies and creeps who currently exercise free reign over us. This book contains a blueprint for those authentic Americans naturally inclined to rebel against the cool culture so lauded by pop culture, media, and academia. I speak of people I consider the Free Radicals—the true nonconformists who reject the lockstep cool that has become our society’s most damaging fetish since autoerotic asphyxiation. Not that I’ve ever tried. I have an irrational fear of being discovered dead, contorted, and naked by concerned neighbors.

Beliefs the cool use to enslave you:

If you don’t agree with them, no one will like you.

If you don’t agree with them, no one will like you.

If you don’t follow them, you will miss out on something great.

If you don’t follow them, you will miss out on something great.

If you don’t give in to them, you will die alone, and unwanted, possibly eaten by your army of starving cats.

If you don’t give in to them, you will die alone, and unwanted, possibly eaten by your army of starving cats.

Fifth grade was when life changed for me. It was during that sweaty, chaotic phase of life I realized there was something far more important going on in the world than saving to buy a speedometer for my Schwinn. It was a time of accidental boners, persistent pimples, and abject fear of, but endless curiosity about, the opposite sex. But it soon became something far more sinister.

It happened one morning, as class began in my suburban Catholic grade school in sunny San Mateo, California. A group of classmates showed up that day with a brand-new attitude and a mysterious excess of dangerous energy. It was as if they discovered a drug, one that tapped a keg of pure idiocy, disguised as higher consciousness.

Previously engaged and impressed by good humor, friendship, and grades, my classmates had changed, their demeanors replaced by something else. Something foreign. Something loud. Something stupid.

Apparently, the night before, they, like millions of impressionable kids around the country, had watched an episode of

Happy Days

, the landmark sitcom about life in the late 1950s or early 1960s, when people still had parted hair and said things like “Sit on it” and “It’s a war wound.” This particular episode’s plot involved gangs. I vaguely remember it, but I’m fairly certain Pinky Tuscadero makes a cameo, Potsie whines, and Ralph Malph cackles like a colicky, freckled rodent. There might have been a Hula-Hoop in the mix, and somebody somewhere in there got “frisky.” I think it was Al.

After they watched the episode, it dawned on my classmates that creating a gang was the thing to do. This decision would instantly elevate them beyond the mundane sweetness of middle school, a time usually spent carving initials into desks and fighting spontaneous arousal with a double coat of underwear (a tip from the always helpful newspaper column Ask Beth). It turned them into rebels.

I think they called themselves the Sharks. And they spent that day, like “sharks,” charging around the playground, running into other, smaller students, all while making idiotic wheezing noises they assumed sharks would make if they survived on oxygen. After instinctively dismissing this unruly new activity as silly and trying to organize some sort of alternative activity (nude four square), I became the target of their bullying. When I tried to reason with them—as much as a fifth-grader with acne can actually reason—I was banished.

And I’ve been there ever since.

This was my first encounter with the destructive superficial charms of cool: middle-schoolers who discovered a brand-new universe where achievement was not required to elevate esteem. This universe, it seemed, didn’t value the actual success you might get from hard work. An animal name and a pack of friends gave these kids the sort of cachet they never had before. They

adopted a new anti-life that had its own rules, and as silly as they were, it was just so much more interesting than everything that came before it. Plus, the girls thought it was neat. Suddenly all of the things that seemed pretty good before—companionship, Wacky Packs, exceptional schoolwork, nude four square—became “stupid.”

It was now cool versus everything else that wasn’t cool. The new world had begun, and I wasn’t on the invite list. Fifth grade had just discovered the velvet rope. And it was held by lowbrow illiterates with snot on their sleeves. (Boogers were a major food group back then.)

From that first time that I found myself ostracized from the gang, I forever learned to beware of anything that smelled of manufactured, attention-seeking behavior. Everything from modern impractical fashion, to hip jargon that means nothing, to contemporary activism that helps no one but the activist sets off my anti-cool alarm.

For all cool was then and all it still is now is a different form of conformity. The more a group of people try to rebel, the more they are trying to fit in. And it is always at the expense of others. Cool is identified only by defining others as uncool. The velvet rope excludes before it invites.