North Yorkshire Folk Tales (11 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

‘Who is the fairest maid in Goathland?’

‘It is Gytha, daughter of Gudron.’

‘Bring her to me!’ says Julian de Mauley.

‘Sire, you have many women to please you. She is only a young virgin. Pease leave her be!’

‘You fool!’ says his master. ‘I do not want her for that but to make this new castle of mine strong. The stones need a life to strengthen them!’

The servant leaps back in horror. ‘Sire, the sacrifice of a cat or a dog will surely be sufficient to protect it. It would be evil beyond evil to kill a maid!’

‘That evil I dare if it will make my castle impregnable.’

The people of Goathland weep and lament when they hear the news, but it is to no avail. De Mauley’s men seize the girl.

‘Who is the best mason in Goathland?’

‘Sire it is Gudron, the father of Gytha.’

‘Bring him here to me. None but he shall lay the stones that will shut his daughter in my wall.’ But Gudron will not come. He swears that he will die before he kills his daughter in such a cruel way.

‘I shall not kill you,’ says Julian when Gudron is at last dragged before him. ‘We shall see what torture will do!’

He hands Gudron over to his soldiers for torture. Gudron is a brave man. He holds out for a long time, but even the bravest may break in time. Weeping, he takes the trowel in his hand to enclose his beloved daughter in the castle wall.

She screams and weeps when they carry her to the place. She begs forgiveness for whatever harm she may have done to injure Julian (for she cannot understand his need).

‘So pure! So sweet! Dear Gytha, you will guard my castle fittingly forever!’

Now the wall rises around her and the darkness with it. Her father tries with broken words to soothe her terror. Now only two stones remain to be laid. A loaf of bread, a jug of water, a spindle and wool are thrust mockingly through into the hole so that she will not waste her last hours. Gytha’s blue eyes stare desperately into her father’s for the last time as he shuts out her world forever.

The people of Goathland beg for her release while there is still time; they fall on their knees before Julian. Priests and monks warn him of holy vengeance for slaying the innocent. Julian laughs at them all, listening with impatience in the dark each night to the fading sound of Gytha’s weak cries far inside his castle wall. At last they cease. Julian rejoices and orders a feast. Now his castle will be impregnable.

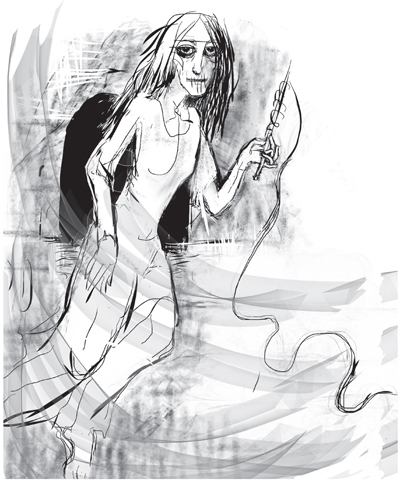

It is a year later. Julian lies asleep. Suddenly he awakes with a jump. There is a light in his room eminating from a drifting figure that moves slowly towards him. ‘Who are you?’ he cries, and then stops abruptly as he sees that the figure wears Gytha’s dress and carries a spindle.

Her face, no longer beautiful, is emaciated, her shrivelled lips drawn back over her white teeth, but it is her eyes, her terrible blue eyes that make him understand that there is no escape. She drifts closer and holds her spindle over his feet. The thread of despair that she spun in her last days snakes down and binds together his feet and ankles, which lose all feeling, becoming cold and dead. Then she is gone. Next day he cannot stand or walk without a stick.

The following year, on the anniversary of her death, she returns and binds his legs with the thread that no one except Julian can see. Now he cannot ride his horse and must be carried on a chair.

And so it goes on year after year, each anniversary bringing a further loss of movement. It is like being slowly walled up. Julian consults doctors, priests and wise women. He covers himself with amulets and charms. He repents and confesses, and swears to do only good. He promises the people of Goathland freedoms they have only dreamed of if only they will pray for him. Maybe they do. But nothing works. On the tenth anniversary of Gytha’s death, his servants find him dead and rigid in his bed. They had no cause to love him, but his death brings them no joy.

‘He was cruel, living,’ they say, ‘God protect us against his spirit now he’s dead!’

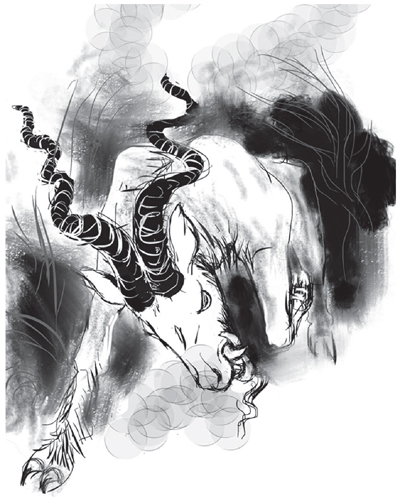

Their words prove prophetic. It is only a matter of months before the people of Goathland realise that Julian in death is indeed worse than he was in life. Labourers going home in the evening see it first: a huge demonic being in the shape of a giant black goat with fiery eyes and curving horns that spout flames. They run as fast as they can, but when they get home one of their number is missing.

‘It’s a gytrash!’ whisper the old women. ‘A gytrash in goat form. Who’d have thought we’d live to see such a thing in our time?’

‘It’s old Julian, if you ask me,’ says the oldest man in the village. ‘He’s come back to destroy us one by one!’

‘Why would he do that?’ asked his little granddaughter from her stool at his side.

‘He never loved the living, and we wouldn’t pray for him. Now he’s dead he hates us still more.’

Now all the villagers are filled with fear. No one dares stray away from home when it gets dark. Children, women and the old are kept indoors, for only the fastest runners can escape the gytrash if they meet it. Even so, many die.

Around the anniversary of Julian’s death, something else begins to haunt the village as well. This time only young maidens are attacked. It is tall and pale, weeping constantly and carrying a spindle in its thin hand. It comes to the girls at night and wraps the wool from its spindle around their chests so that in a few weeks they sicken and die. ‘Gytha blames us for not protecting her!’ the mothers weep.

‘Who will free us from these curses?’ people ask each other. ‘Our young folk seem doomed!’ They pray and they ring the church bells to drive off evil, but nothing stops the ravages of the two spirits. The little granddaughter falls ill. Her grandfather calls a meeting of villagers.

‘There is only one person who can help us,’ he says. ‘We have tried the holy ways, now we must try the unholy ones! Let us go and see the Spaewife of Fylingdales!’

The Spaewife is a witch, white, possibly, but many people fear her strange appearance and cryptic utterances. It is decided that the village elders will approach her. They take a suitable gift and cross the moor to her lonely hut.

After they have explained their problem, her sharp black eyes regard them silently from under her thick white hair. Then she says ‘Tane to tither!’ and shuts her door on them. Not another word do they get out of her.

The villagers discuss the possible meanings of these three words for days. Some think one thing and some another but no one agrees until the old grandfather suddenly understands. ‘We should make t’ane fight t’ither!’

Now everyone can see it. Only a strong spirit like Gytha’s can defeat the gytrash.

‘But how do we get them to fight? Only the Spaewife knows anything about these creatures.’ Back to see her they went.

The Spaewife is pleased that they have solved her riddle. She decides to help them further. ‘Gytrashes are corpse-eaters, grave-haunters. Give gytrash a burial, he’ll be there. Not churchyard, though. Killing Pits. An unbaptised bairn.’

The villagers look at each other in horror; they have no dead babies in the village and if they did, none would be unbaptised, but they dare not argue.

‘What of Gytha?’ asks the grandfather.

‘The pale maid? She’s gytrash’s sworn enemy. Lure her with honey, fix her with wheat and salt. Then you’ll see her come.’

They go home to lay their plans. As they have no real dead baby they make a corn-mell baby (a doll made from the last wheat sheaf at harvest), wrap it in a shawl and lay it in a little white coffin. The village sexton digs a deep grave at the Killing Pits (lumps and bumps of an ancient village a little way outside Goathland).

When the anniversary of the death of Gytha and Julian comes around again the villagers take honey and smear it here and there along the path from the castle to the Killing Pits. They strew grains of wheat and salt along the way as well. Then they wait for evening.

There is a solemn procession walking along the track to the Killing Pits. Hymns are being sung and a small white coffin is carried shoulder high. In its secret lair beneath the castle, the gytrash lifts its horrible head.

The procession reaches the grave and lowers the coffin into it. Prayers are said, though the ground is not consecrated, then the sexton fills in the hole. The mourners melt away, not back to the village but into hiding places in thickets and bushes round about. They wait.

Night closes down. The waning moon gives little light. Owls begin to hoot. A cold wind streams down from Julian Park towards the villagers and with it the distant gleam of flickering flames: the gytrash! Now its fiery eyes light up the path, the flames of its horns stream back over its shoulders. It keeps turning its head searching for the grave. It catches sight of the freshly turned earth and springs onto it. It begins to dig with hooves and horns. It is strong and fast. The waiting people begin to hold their breath. What if it realises it has been tricked before Gytha comes? They can hear its hooves grating on the little coffin. The church bells strike midnight.

But no! Another light is drifting down the road. The emaciated form of Gytha, enveloped in a greenish glow, floats past them towards the grave. The moment she sees the gytrash her blue eyes blaze and her skull-like face contorts as, no longer weeping, she screams her fury. In her hand is her spindle, its deadly thread unspooling as she moves. With the speed of a whip, it wraps itself around the gytrash, binding it to the grave as a spider binds a fly. The gytrash howls and struggles. Its powerful limbs are entangled in the thread; it cannot escape. The sides of the grave begin to cave in upon it. The pile of earth it has dug out slides and topples down, drowning its howls and burying it completely. The ground shakes for a while as the gytrash fights its fate. At last, all is still.

The people of Goathland breathe again and come out of their hiding places. Gytha stands on the new grave. She looks back once towards her former friends and neighbours, and then, throwing her spindle far out over the moor she slowly rises into the air and disappears into the night.

The villagers never see either of them again.

H

OBS

AND

S

UCH

O

N

H

OBS

Western Moors

A list of all the hobs (or hobmen, or hobthrushes, as they are sometimes called) that live in Yorkshire would be a long one. Mulgrave Wood, Runswick Bay, Castleton, Obthrush Roque (Hobthrush Rock!) all had a hob and Pickering was positively infested with them; there was the Leaholme Hob, Hob o’Hasly Bank, t’Hob o’ Brakken Howe, the Scugdale Hob and no doubt many more just called t’Hob.

But what are hobs? The study of hob-lore is esoteric and yet curiously satisfying as they are cheery little creatures with little malice in them – except, like us, when unappreciated. They are related to hobbits – though they tend to dismiss these as ‘Nowt but posh southerners’. They are small, brown, active and, usually, naked (in the Yorkshire climate this implies a considerable degree of toughness).

Like all hob-folk they are hole dwellers, though a few (like the Runswick Bay hob) live in caves. However, whatever hole they live in, they nearly all work in nearby farms, for they enjoy being useful and like the company of humans, with whom they have a pleasantly symbiotic relationship. Hobs excel in farm and domestic work, requiring human payment in the form of a dish of cream or some other food. Money means nothing to them, although they often make the farmer for whom they work rich. Though they themselves are seldom seen and many jobs are done, seemingly at night, any farm where they live is a lucky one where everything always goes well.

It appears that hobs are immortal; though there have not been any reliable studies on this, possibly because they outlive those who study them. They are a sub-branch of the Fair Folk by whom they are regarded as very primitive, principally because of their nakedness (‘So Palaeolithic!’). A hob’s greatest ambition is to acquire clothes, lovely colourful clothes. Only when he – and hobs all seem to be ‘he’ unless, like dwarves, the sexes are indistinguishable, which seems unlikely when one considers their nakedness – only when he has got such clothes will he be regarded as having made it to the big time. Then he will no longer have to hear the scornful fairy cry of ‘Here comes the grubby old hob with never a stitch to cover his ****’. He will instead become a hob aristocrat and never have to work again but spend eternity propping up the bar in fairy hills or footing it featly at fairy balls with his mates.