No Way Down, Life and Death On K2 (2010) (15 page)

Read No Way Down, Life and Death On K2 (2010) Online

Authors: Graham Bowley

Sherpa Pemba Gyalje. A commercial mountain guide from Nepal, he joined the Dutch team as an independent climber in his own right. He wanted to become one of the first Nepalese Sherpas to reach the summit of K2 without the aid of supplementary oxygen.

(Wilco van Rooijen)

Â

The gregarious Gerard McDonnell called his girlfriend in Alaska from the summit. He was the first Irishman to reach the top of K2.

(Wilco van Rooijen)

Â

Fredrik Strang at Concordia on the trek toward K2. The Swedish climber turned back from his own attempt on the summit when he saw the delay on the Bottleneck. Later, he helped bring down Dren Mandic's body.

(Chris Klinke)

Â

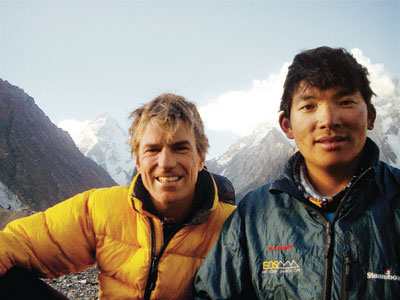

The American Eric Meyer poses with Chhiring Dorje, a Sherpa from Nepal who was a member of the American team. Meyer, an anesthesiologist from Colorado, almost died when his rope snapped on his descent. Dorje helped another Sherpa climb down the Bottleneck in darkness.

(Chris Klinke)

Â

Using binoculars and a telescope, the American climber Chris Klinke sighted Wilco Van Rooijen wandering on the southern face of K2 on the afternoon of August 2, leading eventually to van Rooijen's rescue.

(Chris Klinke)

Â

A close-up of metal plates at the Gilkey Memorial, located a few hundred yards above K2 Base Camp. The memorial is named for an American climber, Art Gilkey, who died on the mountain during an expedition in 1953. Most climbers visit it but few imagine they will end up immortalized there themselves.

(Graham Bowley)

Â

Confortola didn't expect anyone to climb up to rescue them. He knew what he was doing. Back in Italy he had trained in high-mountain safety and rescue and earned extra euros helping stranded climbers stupid enough to venture onto the steep slopes above his house. He brought them in with curses, sometimes snapping their poles over his knee for good measure.

Da Polenza agreed with him.

Be patient.

“Stay there. Wait for the morning.”

Confortola switched off his phone and slid it back into his jacket. “Jesus, let's wait,” he said to McDonnell, using the nicknameâJesusâhe had given the Irishman, and McDonnell agreed.

Da Polenza had warned him to keep warm; there was a danger of frostbite, which was feared by all mountaineers but common in these cold regions of high altitude. As a person's body cools, it directs blood away from the extremities to preserve its inner heat; even when skin temperature falls to 10 degrees, tissues numb, cells rupture. Hands, feet, nose, cheeks are most vulnerable. In 1996, Beck Weathers, an Everest mountaineer, lost his nose and most of his hands to frostbite.

Confortola felt better after talking to da Polenza. To keep themselves warm and to have a perch on the side of the mountain, the two climbers scooped seats out of the snow with a pole and the picks of their ice axes. Confortola made McDonnell's seat slightly larger so he could lie back down. They also made room for their boots.

Even though McDonnell looked exhausted, Confortola knew that

on such a steep slope they couldn't allow themselves to fall asleep. The slope was 30 to 40 degrees and it would be easy to roll down.

“If you want to rest, I'll take care of the situation,” he said.

McDonnell lay back, his blue water bottle hanging from his belt and his black and yellow boots planted in the hole they had cut in the snow.

Confortola turned off his headlamp. It was strange to be up there alone. It was dark and cold. The entire world was stretched out below in shadow. He watched the distant lights of Camp Four, and the single powerful light flashing near the tents. The camp seemed so close. They just could not get down to it. He was convinced they would be able to find the ropes easily in the morning.

At Base Camp, Confortola had gotten to know McDonnell during the final weeks of bad weather. When the storms roared in, the Italian was usually doing nothing much but sitting around in the two-man tent, listening to disco music on his iPod, chewing gum to help with the altitude, or taking long walks across the glacier to keep fit. He started calling in at the Dutch tent to discuss strategy, sometimes bringing bresaola to share, while Wilco van Rooijen or Cas van de Gevel prepared the basic cappuccinos.

He liked them all but he got along best with McDonnell, the handsome Irishman with the wonderful smile. McDonnell had let his hair grow long and had grown a beard, so Confortola had given him the nickname Jesus. McDonnell invited Confortola into his tent and showed him some of his photographs on his laptopâof the waxing moon over K2 or of his girlfriend, Annie, in Alaska or of Ireland. McDonnell took his photography seriously. Neither spoke much of the other's language but they understood climbing.

Outside his tent, above a string of Tibetan prayer flags, McDonnell hung a big Irish flag. He had had it hand-stitched by a tailor in Skardu. Confortola liked to joke with him: “It's just the Italian flag, all mixed up,” he said, poking his friend in the ribs.

Now, as the night deepened on the mountain, Confortola forced himself to shiver to stay warm, gently shaking his arms and legs and clapping. Confortola's body bore the history of his mountaineering life. Tattooed around his right wrist was a Tibetan prayer from his 2004 Everest ascent. Another tattoo across the back of his neck spelled out

Salvadek,

or wild animal, which was how he liked to think of himself. He always wore a ring in his left ear. A self-styled “pirate of the mountains,” at home he was known as a risk taker and head-strong. He liked fast bikes and speed skiing. In the mountaineering community, he was known as a wily survivor, a man with a big heart and good intentions, if also a little vain. Back in Italy, some other climbers called him, half in mocking jest, “Santa Caterina Iron Man.” Around his right bicep he had a ring of six star tattoos celebrating the six peaks above 26,000 feet he had climbed so far in his lifeâsoon now, there would be a seventh for K2.

Away to his left stretched the undulating top of the Great Serac. To his right the slope curved around to a huge gray buttress of rocks and the northern side of K2. In front of him hung the great emptiness beyond the serac.

Somewhere below was the way down into the Traverse. He could still see the light flashing at Camp Four. Everyone else who had made it to the summit must have climbed down onto the ropes and were probably back at their tents by now, he thought. The climbers down there had no idea where they were and if they were alive or dead. He and McDonnell were alone. He didn't know if anyone was still behind them on the summit snowfield.

Confortola was not worried. They were not going to die. They would escape their aerie in the morning. It was uncomfortable, that was all. Cold. To keep his blood circulating, Confortola stood up a few times and walked around the two holes he and McDonnell had dug in the snow.

Then the time passed slowly. The two men were both so cold and

exhausted that Confortola was afraid they were in danger of falling asleep. To keep them awake, Confortola began to hum one of his favorite songs, a song from Italy, from the mountains. “La Montanara.”

Lassu' per le montagne (Up there in the mountains)

fra boschi e valli d'or (among woods and valleys of gold)

fra l'aspre rupi echeggia (among the rugged cliffs there echoes)

un cantico d'amor (a canticle of love).

Beside him, McDonnell seemed to respond to the singing and moved his body.

“Don't give up, Jesus,” Confortola said, and he was saying it to himself as well.

Â

McDonnell was a singer, too. During the bad weather in Base Camp, when many of the climbers feared they would have to cancel their climbs, the Dutch team's camp manager, Sajjad Shan, an impish twenty-nine-year-old Islamabad taxi driver, organized a party to lift the depressed mood. He pushed together three large mess tents and paid an assistant cook to sing, although the cook knew only two songs, one in Urdu and one in Balti. The porters started drumming on the food barrels. Some of the climbers began to dance. An expedition had arrived in camp with seven cases of beer and whisky. The Serbs paid a runner to fetch twenty-four half-liter cans of beer from Askole. Stepping forward into the silence, McDonnell sang a Gaelic ballad that moved some of the fifty climbers packed into the warm tent to tears.

They said the song had to be about the love of a boy for his lass. But McDonnell said, “No, it's about the yearning of a shepherd for his goat.”

McDonnell liked Confortola but then he liked most people at Base Camp. He loved the beauty and isolation of the mountain, but the camaraderie of expedition life also appealed to him. The Dutch team's bulbous tents were perched on the rocks close to the camps of Hugues d'Aubarède and Cecilie Skog. Around Base Camp, McDonnell often carried his video camera, with its small microphone boom, and he filmed the teams' strategy meetings.

On free afternoons, he regularly walked over for a chat with Rolf Bae or with Deedar, the cook for the American expedition. Deedar had cared for McDonnell when he suffered the devastating rock blow to his head on K2 in 2006. Among the Dutch team, he was especially close to Pemba Gyalje and had helped the Sherpa to build a small rock altar for a puja ceremony when they arrived on K2; they played chants from an MP3 player.