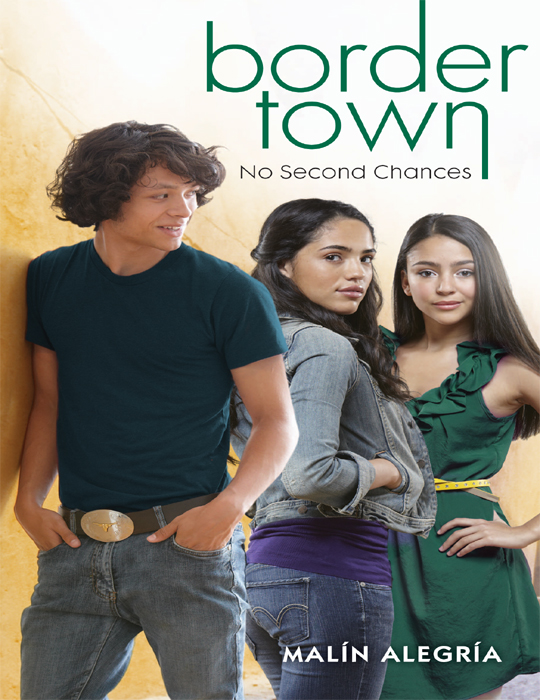

No Second Chances

Authors: Malín Alegría

To

los primos chidos:

Nano, Panchito, Beto

, y

Rickie

Caras vemos, corazones no sabemos.

Â

Faces seen, hearts unknown.

H

ello?” an excited female voice with a thick Mexican accent called through the Dos Rios High wall intercom. “Hello?” she repeated. “Is anyone there?”

A couple of kids in the back of the history class snickered. Sylvia Martinez, the school secretary, considered herself the eyes and ears of Dos Rios High School. Coach Cortez looked up at the wall speaker in annoyance and replied, “Yes, Mrs. Martinez. We can all hear you fine.”

“Oh, good,” she said with relief. “I'm looking for BJ Lopez. Is BJ in your class? His mommy is

out here in the hallway and she has his lunch. She says he has a delicate stomach and that the cafeteria food gives him gas â”

“Mrs. Martinez,” Coach Cortez interrupted. “BJ is not in this class.”

Santiago started to laugh.

“So sorry,” Mrs. Martinez replied before hanging up.

The teacher turned on Santiago with a heated stare. “And what's so funny, Reyes?”

“Nothing, sir,” Santiago grumbled, sinking down at his desk. He held his tongue and tried to reread the paragraph in his opened textbook. Coach Cortez continued to peer from his large oak desk, daring Santiago to talk back.

Damn! This guy has no sense of humor

, Santiago thought. He fought his urge to talk back, remembering his promise to his mother, La Virgen, and even to the trafficker Juan “El Payaso” Diamante: to be good.

Why can't Cortez just cut me some slack?

Santiago noticed that Cortez was scribbling something down on a

piece of paper.

Is he filling out a referral for laughing?

Suddenly, Mrs. Martinez' voice came back on the intercom. “Hello? Hello? Anyone there?”

Coach Cortez crumpled the paper in his hands, grumbling under his breath. “Yes, Mrs. Martinez?”

“Have you seen Santiago Reyes? The pretty boy with the curly hair.”

The room erupted into hoots and applause. Santiago beamed, raising his arms in the air. He couldn't help it that everyone, but Cortez, liked him. The girl next to him smiled.

Mrs. Martinez lowered her voice to a whisper. “I think he's in trouble again. The assistant principal wants to see him and he did not look happy. They called in the guidance counselor and his

mamita

, Consuelo. You remember her, right? Didn't â”

“That is quite enough,” Cortez said, cutting her short. “Settle down, class!” he hollered. Then he pointed to the door. “Go!”

“Sounds good to me,” Santiago said under his breath as he collected his books. He gestured “

adiós

” to his classmates and exited the classroom.

The hallway was deserted. Santiago took in the silence, the wall of lockers, the posters for the upcoming school dance, and the scent of the citrus cleaner the janitor used year after year to mop the floors. He couldn't wait to be done with this place. If he could just keep his cool for a couple more months, he'd graduate onstage with all the other fools.

His footsteps echoed down the hall as he walked toward the assistant principal's office. He wondered what this meeting could be about. Maybe they found out who stuck those fake dollar bills to the ceiling of the girls' bathroom last fall. He snickered to himself, remembering how the girls screamed as they crashed into one another fighting to get the money. Or maybe they found out he was the one who took all the air out of the school bus tires

at the Homecoming game. He'd pulled those pranks way before his promise. Those days â along with his drag racing â were over. They couldn't punish him for things he did last year, could they? Santiago's hands broke out in a sweat. Whatever it was, it couldn't be good, he thought, standing in front of the assistant principal's door.

Why did they have to bring in my mom?

He knocked.

“Enter,” Assistant Principal Castillo said in an authoritative voice.

Santiago took a deep breath and opened the door. Castillo sat behind his enormous desk. On the wall were faded newspaper clip-pings of his former glory days as a high school football star mixed with affirmation posters he'd collected at statewide teacher conferences. Behind his desk there was a recent picture of the Mariachi Club. Santiago spotted his goofy smile in the third row, his accordion raised in the air.

Finally, Santiago noticed the other people

in the room. Two women sat across the desk from Castillo. They both turned around when Santiago entered. He immediately locked eyes with his mother. The pain on her face made him nervous. He wanted to run and deny everything. But his feet were stuck as if nailed to the floor.

The other woman must be the guidance counselor

, Santiago thought, taking in the heavy woman's '80s retro hairstyle and costume jewelry.

“Have a seat, son,” Castillo said, gesturing to the empty chair between the two women.

Santiago couldn't help but flinch at the word “son.” Castillo had been a thorn in his side ever since he started high school. He was always in his business and called his house with any excuse to speak to his mother. But the man wasn't all bad, Santiago reminded himself. Castillo had started that special program to help knuckleheads like him make up school credit; he became the advisor for the Mariachi Club; he'd even pushed Santiago to uncover

a hidden gift for wooing the ladies with the accordion.

Santiago's mom, Consuelo, reached for his hand and squeezed it. Her pained expression alarmed him. Whatever he'd done, he'd make it up to her, he thought. He couldn't stand to disappoint her. It had been just the two of them since his dad left ten years ago. His mom was tall, slender, and had the face of an Aztec princess â the kind you saw on Mexican bakery calendars or lowrider magazines. She could have been somebody big like a TV anchor lady or a runway model.

The assistant principal cleared his throat and glanced at Consuelo. His mom looked down at her lap. What was going on? Santiago's heart raced and a thin film of sweat appeared on his upper lip. He quickly wiped it away.

“Santiago,” Castillo said. The sound of the clock overhead ticked loudly, emphasizing each grueling second inching by. “I have some news about your father.”

Santiago shot up in his chair. “What?”

“Consuelo just informed us that your father is out on parole. He wants to see you.”

“No way!” Santiago shouted. He glared at his mother, begging for her to say it was just a joke. Consuelo held his gaze for a minute. That minute told him that his worst fears were true. “Oh, hell naw. That punk was supposed to be locked up for life.”

“I was worried about how you would take this,” Consuelo said, avoiding his eyes. “I think it might be good for you to see him. John” â she caught herself â “I mean Assistant Principal Castillo thought ⦔

Santiago tuned out the rest of his mom's sentence. John? When did he stop being Castillo? He looked from his mom to Castillo and to the counselor. This whole thing was like a bad case of

chorro

.

“Where are you going?” Castillo barked.

Santiago hadn't realized he had stood up.

Castillo's face softened. “Please sit back down. I know this news is shocking. It was shocking to me, too. Your dad and I used to be friends, did you know that?” His cheeks colored. “I guess what I'm trying to say is that you're not alone. If you ever want to talk â”

His mother cut in, “I hear you've been improving in your classes. He says you can graduate if you pass all your classes this semester. Imagine that” â her eyes sparkled â “my son, a Dos Rios High School graduate.”

Santiago felt trapped in a snare. The thought of his father, a man he barely knew, coming back into his life was unbearable. Why did his mom have to come to school to tell him this in front of Castillo and the counselor lady? Was this some kind of intervention? Did she think he couldn't handle it? Their good intentions were suffocating him.

He remembered the last thing his dad sent him from jail. It was a belated homemade

SpongeBob birthday card. His old man didn't even have the decency to remember his actual birthday. Not to mention he thought Santiago was still a kid. In all the years his dad was locked up, Santiago had never once written or gone to visit him. Now, his dad was getting out and he wanted to see him. Did his mom want them to make up?

“I won't see him. We don't need him, Mom,” Santiago said. “We can move someplace where he'll never find us, and I'll get a job.”

“Santiago,” his mother tried to interrupt.

“No, Mom,” he insisted. “I'm not a little kid anymore. I'm not scared of him. I'll take care of you now.”

Castillo cut in, “Santiago, don't misunderstand the situation. We all care about you and want you to stay focused on your education. Whether you see him or not is up to you. We just don't want you to be surprised if he pops up.”

Santiago shook his head in confusion. His

eyes bounced around the room. These walls were keeping him back from what he really needed to do. The time for school games was over. He had to be out in the real world, making real money. Santiago had to protect his mother. The only way, the real way to do it was with money. He stood up and reached over the desk to shake Mr. Castillo's hand.

“Well, I want to thank you, Castillo, for taking the time to talk to me, hombre to hombre.” The assistant principal looked surprised. Santiago smiled at his reaction. “I want to thank all of you for helping me realize what's really important.” Then he turned to address his mother. He gave her a hug. Consuelo stiffened at his touch. “I don't want you to worry, Mom. I got this all under control.”

Santiago took several steps toward the door.

“You've got fifteen minutes before lunch,” Castillo pointed out, reaching into a drawer for his hall pass slips.

He waved Castillo's offer away with his hand. “Don't worry. I don't plan to go back to class.”

The tension in the room began to build as the adults looked at him with confused expressions. Santiago couldn't help but laugh. They were all well-intentioned, but they were wasting their time on him.

“Where are you going?” his mother asked, the lines at the edge of her eyes creasing. She worried a lot about the mortgage and bills. He wanted to take all those worry lines away. “What about your books?” Consuelo motioned to the history textbook and notebooks he'd left on his chair.

He paused a moment. Their concern was touching. “Give them to somebody more worthy of your support. No, wait. Give them to the hungry children of Mexico, those kids who sell chiclets on the border. Yeah.”

“Santiago.” His mother's tone shifted from concern to irritation. “Get back here. What are you talking about?”

“I'm saying that I'm done playing the schoolboy.” Santiago raised his arms in a surrendering gesture. “This whole education thing I did because I made you a promise. But now my time is up. No more messing around. I'm going to get a job and I'm going to take care of you. I won't let him come near us. We'll go far away.”

“Santiago.” His mother stood up. “What are you talking about? We are not going anywhere. And I won't let you give up on your education.” She looked at Castillo for help.

Santiago smiled. “I'm eighteen, Mom. I can do what I want. You can't make me stay in school.” His mother flinched. He tried to make her understand. “At first I thought graduating would make you happy, but now, thanks to all of you, I see that what I need to do is be a man. I need to make money.”

“That is ridiculous,” Consuelo snapped, crossing her arms in protest. She raised a finger and turned her anger on Castillo. “John, this is all your fault. Do something.”

Castillo cleared his throat loudly, obviously struggling for something to say.

“I know you don't believe me,” Santiago interrupted. “You think I'm just a kid.” His dad's birthday card flashed before his eyes. They all thought he was a kid. A rush of frustration gave him the courage to go on. “But I'll prove to you guys that I can do it.” He opened the door. The adults in the room stared, dumbfounded. Santiago gave them one of his confident smiles. “You gotta trust me,” he said. Then he walked out of the assistant principal's office and Dos Rios High School for good.