No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the World's First Supermodel (37 page)

Read No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the World's First Supermodel Online

Authors: Janice Dickinson

Tags: #General, #Models (Persons) - United States, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Television Personalities - United States, #Models (Persons), #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Dickinson; Janice, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 279

Hello! He beats you when he does recognize you.

But I bit my tongue and rocked my baby boy.

“Why don’t you call him?” she said. “He’d love to hear from you.”

“Look at my little Nathan,” I said, not hearing her, not wanting to hear her. “Isn’t he the most wonderful creature in the world?”

She started filling me in about “our Alexis,” who had become addicted to anything even remotely connected to self-help and self-improvement. Yoga. Meditation. EST.

Rolfing. Actualization therapy. Deep colonics. God. And about “our Debbie,” who’d fallen madly in love with Mohammed Khashoggi, who plied her with rich food and champagne and caviar

and surrounded her with

fawning servants. They

were always on the go.

If Mohammed heard

that a new restaurant in

Cannes had just been

awarded three stars in

the Michelin guide,

they’d hop into his

jet and be there in

time for dinner.

I didn’t speak

much to either of

my sisters in those

days. We each had

THE GREAT NATE!

((((((((((

280 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

lives of our own, clearly, and we all struggled with the usual sibling rivalries. Debbie had been a great model in her own right, but I think she’d lost patience with me. She stopped returning my calls. And Alexis lived in another world. She was growing vegetables and painting and

sculpting with glass, and I was in Hollywood, being a Hollywood wife and mother—though definitely not in that order—and I guess we didn’t have a lot in common.

“It’s a pity you girls don’t talk much anymore,” Mom said.

“Well,” I said. “I try.” But that wasn’t true. I didn’t try at all. I was just as wrapped up in my shit as they were in theirs.

Finally Mom went home and Simon and I went back

to our happy lives. Well,

I

was happy. I can’t speak for Simon. But then his father got sick and died. I felt awful about it. Simon had actually loved his father, been close to him. I wished the reaper had taken

my

father instead.

Within six months, I was pregnant again.

“I don’t want another child,” Simon said. I’d heard that before, and it wasn’t getting better with age.

“Why not?”

“I just can’t fucking cope right now, Janice. My father is dead and I’m feeling lost and I just fucking can’t, okay?”

No, not okay; not really. “Don’t make me have an abortion,” I begged. “It’s going to make me resent you.”

“We’re not having another baby,” he said.

So I had the abortion. And I began to resent him. I knew myself pretty well by that point.

I was unhappy. And very restless. I’d get out of bed in the morning and wouldn’t know what to do with myself. I needed something, but I didn’t know

what.

And then one day I was climbing out of the bathtub, and I looked in the mirror, and I realized that my big lovely tits were gone.

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 281

And I thought,

If I can’t have another kid, maybe I should

at least buy myself a pair of new tits.

I mean, Christ—I deserved a little something.

So I lined up the best tit-man in town. And weeks later, there I was, ready for my state-of-the-art 36-C rad puppies.

Getting wheeled into surgery, already groggy with anesthetic. And I remembered the rat bastard telling me I looked like a boy. And all I could think was,

Just you wait.

Within weeks I was working again, as both a model and a photographer. I went to Antigua and did a shoot for a Chesterfield cigarettes campaign. I took Nathan and the nanny. It was great. I

could

have it all, after all!

I came back and Billy Baldwin posed for me. I shot

Matthew Modine. I shot Dylan McDermott and Randy

Quaid. I shot Carre Otis. I shot Beverly Johnson for the cover of

She.

I shot myself, naked, for the cover of

Photo.

It was sensational. I got a call from one of the top photo agencies, Sygma, asking if they could represent me. I said I’d think about it.

I shot a famous actress, who arrived late and proceeded to behave like a complete bitch. “Hey!” I shouted. “I was a bigger bitch than you could ever hope to be. Now shut the fuck up and get to work.” Her jaw dropped, but she didn’t say a word. The rest of the shoot went beautifully, and we became great friends. (And, no—I won’t rat her out; you’ll have to guess.)

A week later I got in touch with Natasha Gregson Wagner, Natalie Wood’s daughter. I waited for her at a friend’s studio, in West Hollywood, and then there she was, coming through the door: tiny, a little pixie, more waiflike than Kate Moss. But

glowing

somehow—a depth there.

Of course she was a little uncomfortable; it was our first meeting. And I found myself seducing her with the camera.

I was parent, therapist, best friend. I was doing for Natasha 282 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

what the best photographers had done for me: convincing her she was the Center of the Civilized Universe. And it was working.

Then, good God, she said, “I brought this little dress with me. I don’t know why. I had this crazy urge to bring it, so I did.” And she took the dress out of a paper bag, and I looked at it: a plain white dress—

too

plain; a little peasant-style nothing. I didn’t know what to say without hurting her feelings. And before I could say anything, she said, “That’s the dress my mother wore in

West Side Story.

”

Whoa!

In a flash, she’s in her little white dress, looking like an angel, and I’m fluttering, fixing, lighting, arranging, rearranging,

nuturing

. Janice is in total control, baby. In The Zone. And then I’m behind the camera, and I look at Natasha and think,

I can see right through to her soul.

And, click! One shot. A perfect shot. And I know I’ve nailed it. I am

good,

motherfucker. Bad photography is about surface.

Good photography—well, it goes to the core, to the source.

And I’m there. Natasha and I are there, baby.

That perfect shot ran in

Newsweek.

And Sygma called again—and this time I signed with them. My pictures began appearing in

Esquire, Paris Match, Photo.

The work kept me going. And the money kept me in expensive shoes.

Then one day I was at Paris Photo, a studio on La Cienega Boulevard, shooting Naomi Campbell—in the nude—when this buff little guy showed up, unannounced, looking for her. I didn’t recognize him, until I took a closer look. It was Sylvester Stallone. I couldn’t believe how short he was. I felt like laughing, but I managed to stifle myself.

“What are you grinning about?” he asked.

“Nothing,” I said.

“So where’s Naomi?” he asked.

“She’s changing,” I said. “But I’m not done with her yet.”

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 283

“Well, can I have a lousy minute?” he barked.

“Sure,” I said. “If you’ll pose for one picture.”

He walked across the room and turned to face me and tucked his hand down the front of his pants.

“Anything interesting down there?” I asked him.

“Something

you’d

like,” he said. “Bam

ham slam.”

“Looks like a dead

rat,” I said, and snapped

his picture.

“It’s just resting,” he

said, and Naomi

walked in.

“Who’s resting?”

she asked.

Sly crossed the

room and took her in

his big arms and kissed

her.

“Yum,” she said.

A few days later,

Naomi came by the

house to see the proofs.

She looked great. And

Mr.

Stallone looked

great in that one shot.

“What’s he doing

with his hand down his

pants?” Naomi asked.

“I don’t know,” I

said.

“Testing

the

equipment.”

“Let’s go show him

284 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

the pictures,” she said.

“What? Now?”

“Sure,” she said.

So we went over to his house and showed him, and in typical actorly fashion he was only interested in the one of him. “Pretty good,” he said.

“Pretty good?” I shot back. “You look awesome.”

Naomi went to find a drink.

“I want to publish it,” I said. “What do you think?”

“We can talk about it over dinner,” he said.

“I’m a married woman,” I said.

“So what?” he said.

“You must have a little French blood in you,” I said.

“Huh?” he said.

“Forget it,” I said.

I went back home and resented Simon. I couldn’t help it. I’d never been much good at letting go of anger.

I filled the growing emptiness within me by having people over. I had parties at the drop of a hat. Everyone came.

Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer. Iman. Naomi. Diane Keaton. A lot of people named Peters. Bernadette Peters.

Jon Peters. Corinne Peters. And Peter Peters, one of the world’s great dry cleaners.

Sly came to dinner one night, with Naomi. When she

was out of earshot he told me the “dead rat” was feeling a little twitchy. I looked hot that night. I was wearing Manolo pumps and a dress that looked like it was spray-painted onto my perfect-again body.

“I thought Naomi was taking care of the rat,” I said.

“You’re the real deal,” he said.

“You’re weird,” I said, and moved off.

A few days later, I got a letter from Pam Adams’s

mother, in Florida. Pam was dying of cancer. I took the next flight to Fort Lauderdale and went directly to Holly

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 285

wood Memorial Hospital, where my mother still worked.

“Pam talked about you often,” Mrs. Adams said. She’d always been distant, and distant she remained. “She told me she wrote you from Paris.”

“That’s right,” I said, remembering that short, mysterious note.

“She was fighting the cancer,” Mrs. Adams explained.

“She had gone to Europe looking for a cure. They had some experimental drugs in Europe that weren’t available in the States. But of course they were expensive.”

I felt like dying. I’d been right: Pam

had

wanted money for drugs, but not the types of drugs I’d imagined. I wondered why Pam hadn’t explained. But what could she have said? “I’m dying. Can you help

me?” How do you reach out

from such a distant place?

“I wanted to call you while

there was still time,” Mrs.

Adams said.

But there wasn’t time. Pam

was in a coma. She had developed a particularly aggressive form of melanoma while living in the Caribbean. She’d first noticed it as a little spot

on her back, while she was

out island-hopping on a

sailboat, and she’d ignored

it. By the time she went to

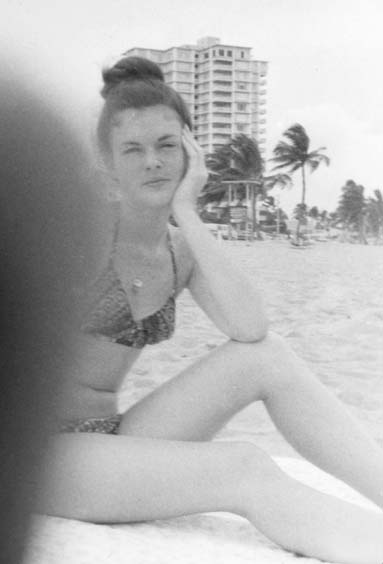

PAM ADAMS IN FLORIDA

WHEN WE WERE KIDS.

(((((((((((((

286 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

see a doctor, it was too late.

I couldn’t get over the sight of her. She looked beautiful. She was hooked up to all these monitoring devices—her heartbeat was slow and steady—and she was done up beautifully. Every hair on her head was lovingly combed, perfectly arranged against the bright white hospital-issue pillow. She was wearing makeup. Her fingernails were perfect. Her hands were laid out flat on either side of her body, looking pale and pink against the bedspread. I cried—I couldn’t help it—and Mrs. Adams left the room. I pulled the chair closer to the bed and told Pam I was sorry. I was sorry we’d lost touch. I was sorry I’d never answered her letter. I was sorry she was sick.

“Please don’t die,” I said. “I want you to meet my little boy, Nathan. He’s wonderful. You’ll love him. Maybe you could be his godmother.” I just talked and talked. About my love life, such as it was; about the ups and downs of my career. I told her about L.A., that Simon and I had plenty of room for her, and that as soon as she was up and about I wanted her to pack her things and fly out. “I’ll pick you up at the airport,” I said. “You’ll move in. It’ll be like old times. We’ll be kids again.”