No Joke (18 page)

Authors: Ruth R. Wisse

Portnoy breaks taboos not by bedding Gentiles but rather by insulting them. Now

this

was novel. There was nothing new in Jews making fun of other Jewsâof Judaism, Zionism, the Jewish family, Jewish law, prayer, the Bible, or even God. But a Jew spoofing Christianity

in the language of Christians

was another matter. Repression in Jewish culture began with repressed aggression against the majority that determined one's degree of security and prosperity. Yiddish may have had its unflattering terms for Jesus, the convert Heine did a number on von Platen, and Bruce declared Jewish and goyish open to self-definition: “I'm Jewish. Count Basie's Jewish. Ray Charles is Jewish. Eddie Cantor's goyish.” But not since Masada fell to the Romans had Jews gone up with such brio

against the majority. Anti-Christian jokes had been reserved for

Jews

who passed over to Christianity and intramural consumption. In contrast, when Portnoy sees a picture of “Jesus floating up to Heaven in a pink nightgown” tacked up over the sink of Bubbles Girardi, he goes after Christianity more eagerly than after the girl he hopes will cure his virginity:

The Jews I despise for their narrow-mindedness, their self-righteousness, the incredibly bizarre sense that these cavemen who are my parents and relatives have somehow gotten of their superiorityâbut when it comes to tawdriness and cheapness, to beliefs that would shame even a gorilla, you simply cannot top the

goyim

. What kind of base and brainless schmucks are these people to worship somebody who, number one, never existed, and number two, if he did, looking as he does in that picture, was without a doubt The Pansy of Palestine.

27

About to test his manhood, Portnoy apparently first wants to prove his Jewish potency, and this he does in the only way he can: by establishing that he is not a goy.

True, there is something belatedly adolescent in all this; intellectually as well as emotionally, that is the stage of life in which Portnoy is stuck. Yet those who worried lest

Portnoy's Complaint

stir up Christian backlash against the Jews were as out of date as Syrkin and Scholem in their analogies with Nazi Germany. If Bruce's improvised distinctions between Jewish and goyish mocked the increasingly unstable identity of Jews in the United States, Portnoy's riffs on Christianity a decade later responded to America's declining confidence in

itself as a Christian country. Roth was enough at home in the United States to know this. Humor hits a person when they are down, and Roth could hardly pass up the opportunity to include Christianity in America's rapidly expanding gallery of vulnerable targets.

From the perspective of this book, what interests me most about

Portnoy's Complaint

is its take on the subject of Jewish humor itself. Roth said that in writing the novel, he was influenced by Henny Youngman (Henry Junggman) along with the tradition of stand-up comedy that had boomed in the Catskills and was becoming a mainstay of U.S. television. At least on second reading, if not on first, the novel seems more warning than tribute, as Alex declares himself trapped in the Jewish joking that was supposed to be his salvation: “Doctor Spielvogel, this is my life, my only life, and I'm living it in the middle of a Jewish joke! I am the son in the Jewish jokeâ

Only it ain't no joke!

” And a little later:

A Jewish man with his parents alive is half the time a helpless

infant

! Listen, come to my aid, will youâand quick! Spring me from this role I play of the mothered son in the Jewish joke! Because it's beginning to pall a little, at thirty-three! And also, it

hoits

, you know, there is

pain

involved, a little human suffering is being felt, if I may take it upon myself to say soâonly that's the part [the comedian] Sam Levenson leaves

out

! Sure, they sit in the casino at the Concord, the women in their minks and the men in their phosphorescent suits, and boy do they laugh, laugh, and laughâ“Help, help, my son the doctor is drowning!”âha

ha

ha

, ha ha

ha

, only what about the

pain

, Myron Cohen! What about the guy who is actually drowning!

28

Portnoy has expected his lie-down comedy to move him beyond the smothering taboos he thinks are keeping him weak and needy. But like Sholem Aleichem's monologues that end with the rabbi passing out or the listener trying to strangle the man seeking his advice, Roth's shtick overwhelms its subject. His bid for liberation fails. In the joke about the drowning son that he cites, the mother's incongruous boast punctures her and our anxieties at the moment he is going under. But Portnoy draws our attention back to the drowning. In trying to manage the crises of Jewish experience, Jewish humor had reached a tipping point.

Portnoy's Complaint

warns that the cure, laughter, may be worse than the disease. A strategy for creative survival may have become a recipe for defeat.

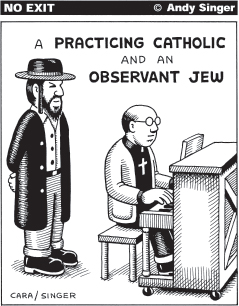

Jews and Catholics are among the favored targets of cartooning, which can identify them visually by their clothing. Courtesy of Andy Singer.

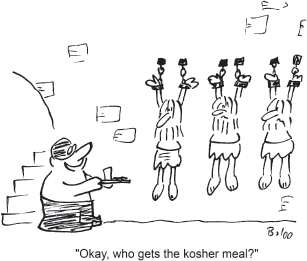

Victimhood and the kosher laws figure in this version of gallows humor. Torture and the dietary laws represent contrasting methods of discipline and self-discipline. Courtesy of

www.CartoonStock.com

.

As Roth might put it: Does Portnoy eat pussy and warn against it, too? First exploit the vulgarity, indulge the eroticism, roll out the high-spirited comedy, and then extravagantly confess to having failed? A preachy edge to the satire occasionally attests to another kind of failure:

And instead of crying over he-who-has-turned-his-back on the saga of

his people

, weep for your own pathetic

selves, why don't you, sucking and sucking on that sour grape of a religion! Jew Jew Jew Jew Jew! It is coming out of my ears already, the saga of the suffering Jews! Do me a favor, my people, and stick your suffering heritage up your suffering assâ

I happen also to be a human being

!

29

When he loses control over the comedy, the narrator sounds like an ordinary sap. The same may be said of the novel's final chapter, which consists in its entirety of Dr. Spielvogel's “punch line”: “Now vee may perhaps to begin.”

30

The book is reduced to less than the sum of its parts. Still, in the roll-out of American Jewish comedy, Roth's book was the first to sound the warning that arises from among the best of its practitioners.

4

Under Hitler and Stalin

I told jokes, and everything inside me wept.

âShimen Dzigan,

The Impact of Jewish Humor

From its beginnings in the 1920s and with mounting force in the 1930s, Hitler's anti-Jewish propaganda powerfully affected neighboring Poland in the form of anti-Jewish pogroms, discriminatory laws, economic boycott, and prejudice from once-friendlier fellow citizens. Mass emigrationâthe time-tested Jewish answer to oppressionâwas blocked by closed borders in the lands of potential refuge. In a paradox characteristic of other modern Jewish societies under pressure, the growing sense of siege that pervaded the Jewish communities of Poland stimulated an already-booming culture. The Association of Jewish Writers and Journalists in Warsaw grew from a membership of sixty when it was founded in 1916 to over three hundred when the Germans invaded in 1939; it sent out speakers to Polish towns and cities while sustaining a network of competing newspapers, journals, and publishing houses in the capital. There was also an increased need for entertainment that would distract or temporarily release the tension, and offer consolation.

Professional comedy was part of this ferment. While American Jewish comedy was ripening among vacationers in the Catskills, its Polish counterpart developed in urban theaters that specialized in Jewish entertainment. The Yiddish theater attracted mixed audiences of Jews and liberal Gentiles when it performed serious plays and works from the international repertoire, but comic entertainers appealed to insiders looking for more intimate as well as lighter fare. The leading Jewish comedians in Poland, Dzigan and his partner Yisroel Schumacher, reached the peak of their fame in Warsaw in the years that Hitler was consolidating his control over Germany. As against the attempt of Yiddish “high” culture to overcome dialectical variance by imposing “Lithuanian” Yiddish as the standard language, this duo exploited the regional accents and homespun argot of their native Lodz for comedy's sake.

Through trial and error in the small-scale Yiddish chamber theater (

kamera teater

) where he made his start, Dzigan developed the comic persona of a traditional Jew, dressed in black caftan and hat with a distinctive red handkerchief as his emblem and propâan intimate and familiar figure who could be trusted as he went about the business of spoofing his audience. How does an old-world character manage the novelties of modern life? In one routine, he came on stage playing with a yo-yo, whose many uses he demonstrated by strapping it to his arm in the form of tefillin, prayer phylacteries, then dangling it as a pocket watch on a golden chain. His wife, he explained, used the yo-yo instead of potatoes for her sabbath stew; his daughter had just given birth to yo-yo twins; but a brother-in-law couldn't have children because his yo-yo didn't work.

Dzigan's rapid-fire patter was a lot like Groucho's, but rather than neutering Jewishness for a general public he played up its specificities. Some of the duo's barbs were lifted from early Enlightenment satire, “translated and improved” (as the Yiddish theater claimed about its versions of Shakespeare's plays) to bring it up to date.

Politics became part of their stock-in-trade. In their description of a fatal hunting accident, Field Marshal Herman Göring is mistaken for a pig. Although it was safer to ridicule German than Polish targets, audiences laughed hardest at local ones. A popular routine brought onstage the anti-Semitic priest Stanislaw Tzeciak, whose agitation had often led to violence against Jews. Passing himself off as a scholar of the Talmud, Tzeciak had accused Jews of using their religion to dominate othersâfor example, by inventing the practice of ritual slaughter of animals as a means of controlling the meat industry. The stage priest spouts what the audience recognizes as absurd interpretations of the Talmud. As he walks offstage, he boasts of his Jewish brainsâ“What does the Talmud call it? Oh yes,

tukhes

.” He points to his head while alluding to his rear end.

A riskier skit was “The Last Jew in Poland,” which played out the consequences of anti-Semitic ethnic cleansing. An earlier dystopian novel by Hugo Bettauer,

The City without Jews

, had envisioned Vienna stripped of the creative tenth of its population. Similarly, in the Dzigan-Schumacher version, a

judenrein

Poland produces a stalled economy and decimated culture, thereby triggering a frantic attempt to reverse the process. The Jew who has been the slowest to join the exodus of his people finds himself besieged by citizens begging him to stay. He is feted at a banquet with gefilte fish, cholent, and Jewish entertainment, and given a medal, which he promptly pins to his backside next to his Polish Cross of Merit. This “insult to the Polish nation” almost got the comedians arrested. Since the Polish censors sometimes closed offensive acts after the first performance, ticket sales were brisk for the duo's opening nights.