No Higher Honor (14 page)

Authors: Bradley Peniston

But there was another feeling, too: eagerness, an adrenaline trickle. It was a natural feeling of a naval officer in his twelfth year of service, especially one who had spent two solid years preparing himself, his ship, and his crew for a fight. The time had come to ride his warship into harm's way. “This is basically what I'm getting paid for,” he said. “I'm putting my money where my mouth is. I'm not going to say I'm not afraid. But it's a healthy fear, a respect.”

44

The family gathered in the early morning darkness, and Palmer asked God to see them through their six-month separation. Then they climbed into the Caprice station wagonâlittle Rachel squeezed between her brother and sister in the backseat, her parents holding hands in frontâand drove the five minutes to the naval station.

At the pier, Palmer embraced his wife and hugged his children. Then, as dawn broke, he turned and strode toward the gray form of his ship, dark against the cloudless sky.

Around him, shipmates were saying their own farewells. Most of the crew was already aboard ship; they were young and single, most from towns and cities far from Rhode Island, and had no one to see them off. Such was the final addition to the crew, Christopher Pond, a hull technician third class. Pond had slipped aboard just hours earlierâ2:00

AM

, as a matter of factâand had received surprising news from the petty officer on duty at the quarterdeck. “You still have four more days of leave left,” the petty officer said, fingering a date on Pond's transfer documents. “I would take it if I were you.”

45

Pond had listened in disbelief. His orders had said nothing about his new ship's imminent departure or its destination. A native of Lebanon,

Pennsylvania, the nineteen-year-old was just back from a two-year tour aboard a support ship moored near the Italian island of Sardinia. The hull technician was still readjusting to life on American soil, and the idea of setting off on a six-month deployment before lunch arrived as something of a shock. For a moment, he was tempted to take his hard-earned leave and let the navy worry about getting him to the

Roberts

after it departed. Then he shrugged.

Better to stay aboard than be shuffled around the world trying to catch up to my ship

, he thought.

At 9:00

AM

a navy band played “God Bless America,” and the frigate moved away from the pier. A small clot of family and friends waved as the ship headed out into the blue-gray Narragansett Bay. Moments later, another frigate pushed away from an adjacent pier:

Roberts

's squadron-mate USS

Simpson

(FFG 56). One after the other, the warships passed beneath the long suspended span of the Jamestown Bridge, south past the rocky Dumplings, and out toward the Atlantic Ocean.

Left behind on the Newport pier was Aquilino. For eighteen months the commodore of Surface Group Four had guided and supported the

Roberts

as it proceeded from a newly commissioned watercraft to a deploying warship. Now he could only watch the frigate go with a mixture of pride, concern, and envy. Later that afternoon, he sent a message out to the departing ship, wishing them Godspeed as they headed for the closest thing the navy had to a front line.

46

Three years of training had forged the

Roberts

's two hundred and fifteen sailors into a fighting team. Thousands upon thousands of hours of preparation had honed their skills. But drills couldn't compare to duty in the Gulf, where the action lasted not hours but days and weeks. And thoughts of

Bridgeton, Sea Isle City

, and

Stark

hung like specters in the salt air.

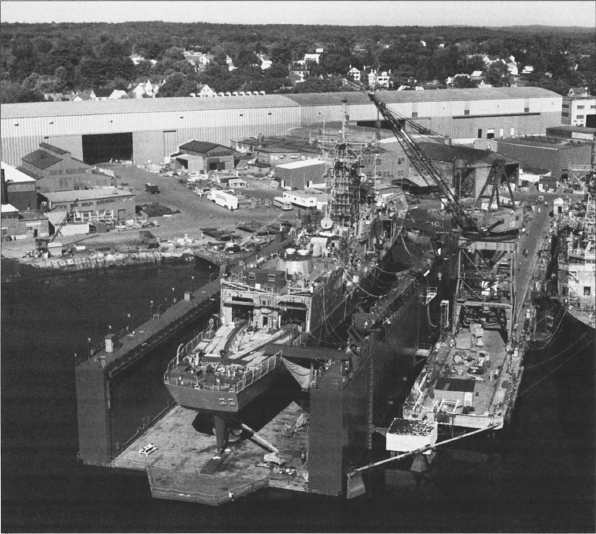

Samuel B. Roberts

(FFG 58) being outfitted in the dry dock at Bath Iron Works in Maine, ca. summer 1985.

Courtesy General Dynamics Bath Iron Works

Roberts

, ca. 1986.

Courtesy Eric Sorensen

Courtesy Nathan Levine

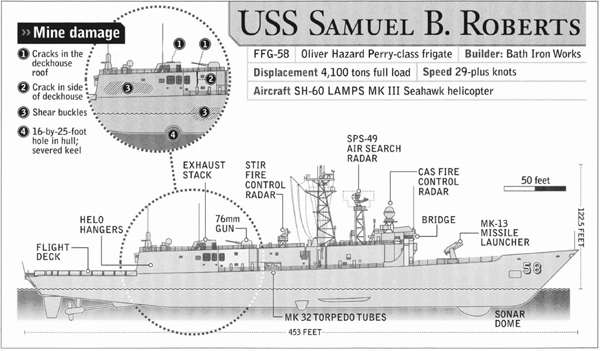

Chris Stopa

Samuel B. Roberts

shows mine damage.

Courtesy Nathan Levine

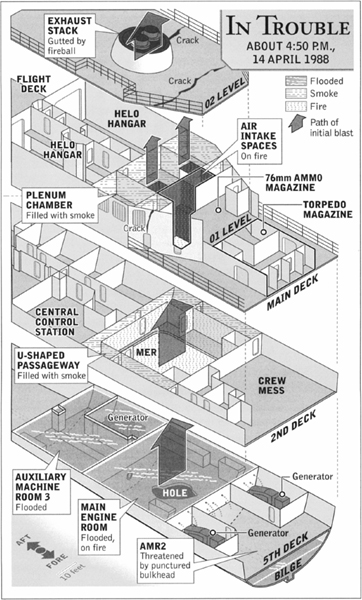

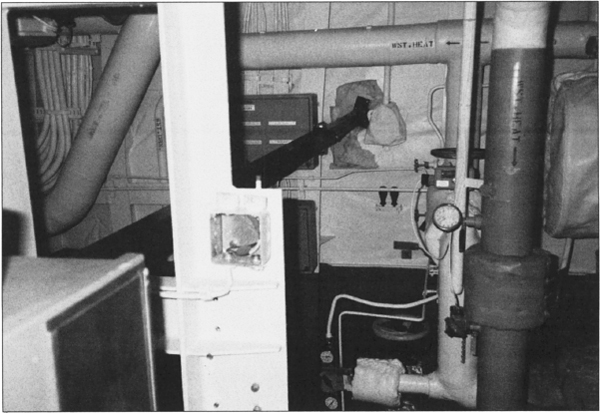

Roberts

shows fire, flood, and smoke damage.

Courtesy Nathan Levine

Courtesy Eric Sorensen

Courtesy Eric Sorensen

Courtesy Eric Sorensen